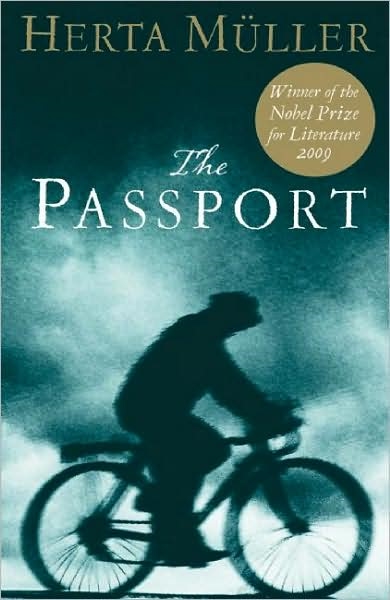

Book Insider: The Passport by Herta Muller

Winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature, Herta Müller was born into a household of German-speaking Romanians, a minority group in a remote village in Banat who were deported to the Soviet Union in 1945. Müller’s mother was sent to serve five years in a labor camp in the Ukraine. From 1973 to 1976, Müller attended the university in Timisoara (Temeswar), majoring in German and Romanian literature. She soon joined a circle of dissident young German-speaking authors known as the “Aktionsgruppe Banat,” opposing the new Romanian dictator, Ceausescu. From 1977 to 1979, Müller found work as a translator at a manufacturing company. When she refused to be an informant for the secret police, she was dismissed, and afterward she was continually harassed by the Securitate. In her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Müller spoke powerfully about this period in her life:

Winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature, Herta Müller was born into a household of German-speaking Romanians, a minority group in a remote village in Banat who were deported to the Soviet Union in 1945. Müller’s mother was sent to serve five years in a labor camp in the Ukraine. From 1973 to 1976, Müller attended the university in Timisoara (Temeswar), majoring in German and Romanian literature. She soon joined a circle of dissident young German-speaking authors known as the “Aktionsgruppe Banat,” opposing the new Romanian dictator, Ceausescu. From 1977 to 1979, Müller found work as a translator at a manufacturing company. When she refused to be an informant for the secret police, she was dismissed, and afterward she was continually harassed by the Securitate. In her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Müller spoke powerfully about this period in her life:

“[The Securitate man] called me stupid. [He] said I was a shirker and a slut, as corrupted as a stray bitch. . . . I stopped writing. I put down the pen and went to the window and looked out onto the dusty street, unpaved and full of potholes, and at all the humpbacked houses. . . . On Glory Street a cat was sitting in a bare mulberry tree. It was the factory cat with the torn ear. And above the cat the early morning sun was shining like a yellow drum. I said: N-am caracterul—I don’t have the character for this. I said it to the street outside. The word CHARACTER made the Securitate man hysterical. He tore up the sheet of paper and threw the pieces on the floor. With his briefcase under his arm he said quietly: You’ll be sorry, we’ll drown you in the river. I said as if to myself: If I sign that, I won’t be able to live with myself anymore, and I’ll have to do it on my own. So it’s better if you do it.“

The Passport is the English translation of Der Mensch ist ein grosser Fasan auf der Welt (Man is a great pheasant in the world), written in 1986. It is a novel (or novella) about a Romanian (ethnic German) man,Windisch, a village miller, who searches a way to bribe the communist officials for a passport which will allow him and his family to return to West Germany. It is written in a surrealistic style, and if the translation is similar to the original, it is written in short, paratactic sentences and fragments, all in the present tense.

Each vignette tells us another story about those Germans left behind the Wall struggling to return to Western culture and government. Müller depicts the desolate remains of their farmlands with fierce intensity:

“It was summer and the village was parched. And water from the well wasn’t rain water. . . . For seven days the sky burned itself dry. It had wandered to the end of the village.”

In Müller’s work we are thrown off-balance by images that tumble rather than fall into place, never quite sure how each image will blend into another. Müller creates a severe, desolate world. Even the natural objects—poplar trees, animals, clouds, and rivers—cry out in despair and futility. Only women can sustain life, although they do this compromised and violated, suffering under conditions of personal degradation and impoverishment. The female and her sexuality is a recurrent and persistent theme throughout the novel. The female is both whore and mother, and, like the nature that subsists and endures despite its impoverishment, she is the carrier of seed and sun, bringing regeneration and light to each family’s feelings of despair and discoloration. Müller pedals through the thickets with her own set of wheels, mobilizing and reasserting these themes of gender and the regime’s contempt for women.

“There are women everywhere, ” the night watchman says in the novel, “There are even women in the pond,” And later, he says sarcastically: “God knows what they’re for, women. . . . Not for us, not for you. I don’t know what they’re for. . . . And our daughters. . . . God knows, they become women too.” He tells Windisch about the Walachian Baptists in the town and their loose women: “They do it on the carpet in the prayers house. . . . The religion comes from America. . . . That’s across the water. . . . The devil crosses the water, too. They’ve got the devil in their bodies. . . . Yes, the Jews are the ruin of the world. Jews and women.”

As Windisch repeats his habitual patterns, Müller carefully builds to the book’s final revelation. It will be not Windisch by Amalie, his virgin daughter, who will secure passports for her family. And she will achieve this by offering her young sex to the officials for their pleasure-taking. Like the white dahlia, the flower which has miraculously survived a long, brutal drought, depicting the most dramatic image of the female’s enduring capacity to carry seeds, she withers from the compromising of her ethics and soul, but she nonetheless carries the seeds of fertility towards a future, her “petals falling off”, but the source of her power remaining voluptuous.

In her Nobel Prize acceptance speech last year, Müller asked:

“Can we say that it is precisely the smallest objects—be they trumpets, accordions, or handkerchiefs—which connect the most disparate things in life? That the objects are in orbit and that their deviations reveal a pattern of repetition—a vicious circle, or what we call in German a ‘devil’s circle’?” Her answer was that, “We can believe this, but not say it. Still, what can’t be said can be written. Because writing is a silent act, a labor from the head to the hand.”

Herta Muller will visit Bucharest at the end of September. She will attend an event on September 27 at the Romanian Atheneum called 'Herta Muller in dialog with Gabriel Liiceanu', which will be followed by a public book reading session. Two of her novels will also be released on September 28 in Bucharest at the Humanitas Kretzulescu bookshop.