The archive showcasing a century of public and private life in Romania in analog photography

Photography has always played an important part in the family of Edgár Szőcs, the initiator of Azopan. His paternal grandfather was an amateur photographer, just like his father, who was also a member of the photo club in Târgu Mureș, while his mother worked at the photo materials plant in the city. He started taking photos at an early age, when he was eight years old. Although he didn’t choose photography as a profession, he maintained a passion for the domain and an interest in safeguarding the legacy of analog photography.

The basis of the Azopan archive was his family collection of photos. With so many around him in contact with or having an interest in photography, there was a larger-than-usual lot available. As an adult, he had the idea to gather the photos so they would not get lost, and after a while, he started digitizing them. As he was scanning them, he realized some images were not necessarily private and could be of interest to a broader public. He planned to group them all in an archive, but it was nothing more than an idea until 2010, when the Fortepan archive emerged in Hungary. It served as an inspiration for Azopan in how they developed their collection and presented the images, Szőcs explains. Similarities can be found down to the name. Fortepan was a Hungarian brand of black-and-white film, while Azopan was the Romanian brand for the same product.

Beginning in 2014, he started collecting and digitizing photos more consistently, and in 2017, he reached out to two high school colleagues - Lóránd-Félix Furó and Lóránd Fülöp - with the project of the archive. One is a pastor but also a photographer, the other is a programmer; together they founded Azopan, which became available to the public in 2018.

Some 20,000 photos are published in the online database, but the collection is considerably more extensive, reaching around 100,000 photos digitized, and just as many materials are waiting to be processed. Maintaining and developing the archive is a labor of love. “We don’t have the time to process everything quickly,” he says. “It’s a passion for us, and we do it in our spare time.”

The idea of developing the archive from donations was there from the very beginning, taking a cue from Fortepan. “At the beginning, we even ran some ads in newspapers in Târgu Mureș asking people to donate if they had photos and didn’t know what to do with them. It’s the model we took over from Fortepan.” Azopan, which is constantly receiving content, now includes photographers’ collections provided by the families or by the individuals themselves, various private donations, and even contributions from several museums.

“On the one hand, we do the research and search for photos, and on the other, we received many items as people learned about the project and contacted us to donate photos and materials.” In some instances, Azopan was only in charge of digitizing the photos and received the permission to publish them.

The archive includes photos from all over the country, sometimes from abroad as, even during Communism, some people took trips outside of Romania. “Because we are from Târgu Mureș, we probably have more photos from Ardeal [the region of Transylvania]. It just happened, but we have photos from all over the country,” he explains.

Târgu Mureș, a city in central Romania, has its own place in the history of local photography as it hosted the only photo materials factory in the country (Uzina de Materiale Fotosensibile Azomureș) between 1981 and 2003. A predecessor was the workshop set up in 1947 by the brothers Imre and Attila Horváth, also from the city, where photographic paper was produced. The enterprise was meant to solve the shortage of photo materials after the war, which their sister, a photographer, and many others faced. It was nationalized in 1949, and, in time, it evolved into a small plant backed by government funding. Until the opening of the newer plant in 1981, it produced various types of photo paper, but not film. In the 1970s, it was assigned to Azomureș, where the larger project of a photo-sensitive materials plant was later developed.

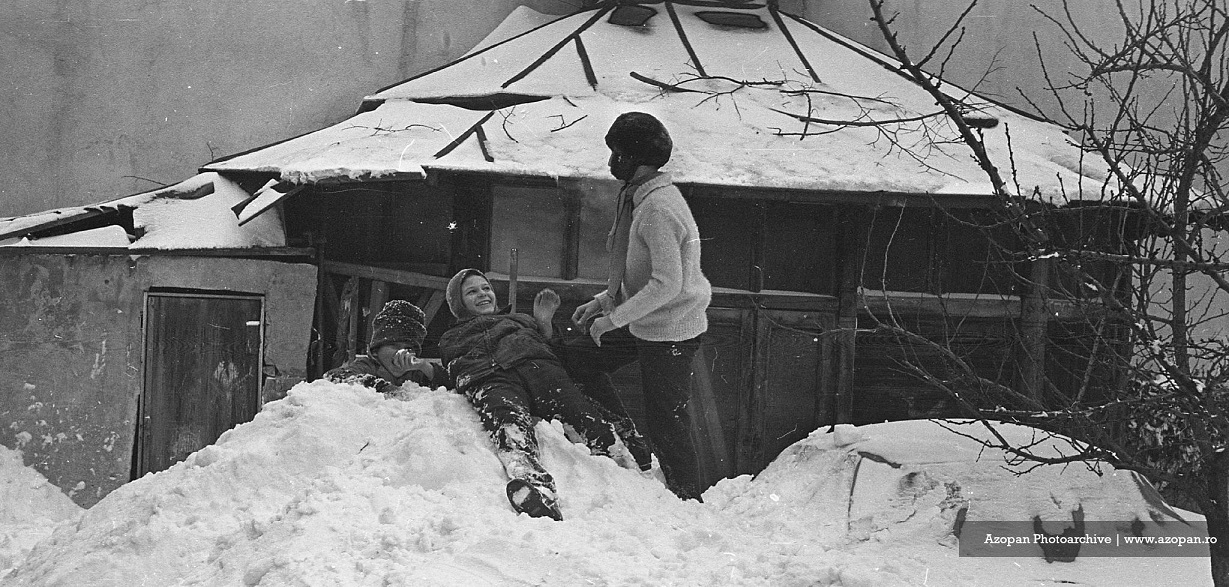

Outside of the copyright criteria, a variety of images have been and can be added to the archive. “We just look to see if it is something that could be interesting. Does this photo document something that maybe in time could prove of interest?” It can be snapshots of cities that, in a few decades, will no longer look the same, portraits, scenes of domestic life, and historical or public events, gathered with the understanding of the nostalgia people have when looking for things from their childhood or their hometown but also how subjective the experience of contemplating a photo can be. They are all available for anyone to browse, download, or share.

Looking forward, the project is set to expand with additional contributions. “We collect, digitize, publish, store, date, research. It would be useful to have some volunteers to help, and it would be good if we could take the time to find some funding,” he explains. So far, any costs associated with equipment or various trips were covered by the project founders. “I do it because I like it. I’ve put thousands of hours into the project.”

As a first this year, Azopan received funding from the Administration of the National Cultural Fund (AFCN) to handle the digitization of the magazine Új Élet (New Life), a Hungarian-language culture and society magazine published in Târgu Mureș between 1958 and 1996. The digitized issues of the magazine and the photos used to illustrate it are available in the online archive. Anyone interested can also see which magazine issue they find the respective photo in. For the project, they worked with the Mureș County Library, where a large part of the magazine’s archive was available, and digitized all the photos they found so far. “Some of the photographers who worked for the magazine, when they left, they took some of the negatives, but we are trying to find as much as we can. It is pretty interesting, for us at least.” All in all, it's another step in preserving and sharing the local analog photography heritage.

(Opening photo: a student festivity in Sighisoara in 1980, photo by Klaas Eldering from Azopan.ro)

simona@romania-insider.com