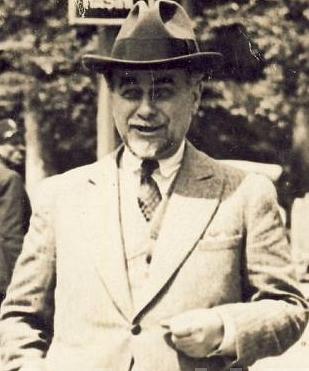

Bucharest Centennial: Dem I. Dobrescu, the mayor of the capital of the Great Romania

Check the full series of articles dedicated to the Centennial on Romania-Insider.com here.

Eleven years after the Great Union of 1918, the leadership of the Bucharest City Hall is taken over by Dem I. Dobrescu, one of the mayors who would bring multiple transformations to the capital of Great Romania. It is the time of the interwar development and the capital is going in the same direction, led by one of the most active mayors it ever had.

Born into a family in Transylvania, Dobrescu quickly stood out with his eloquent style, practiced as a teenager when he argued the case of his village inhabitants in front of a judge. After graduating from the Law School in Bucharest, he furthered his studies in France, where he also obtained his PhD with the paper titled L'évolution de L'idée de Droit (The Evolution of the Idea of Law). After returning to the country, he worked as a judge with the Iași Tribunal and afterward as a prosecutor with the Ilfov Tribunal. He also became a dean of the Bucharest Bar and president of the Lawyers’ Union.

At the 1926 elections he became a mayor of the District III Blue, and in 1929 he took over as mayor of the capital, a position he held until 1934, thus becoming one of the longest-serving mayors of Bucharest.

His mandate covered extensive systematization and urbanization works, but also social and cultural components. Dobrescu also had to work to overcome the inertia or the opposition shown to the projects he was proposing in his endeavor to turn the city into an exemplary capital.

In the work Viitorul Bucureștilor (The Future of Bucharest), Dobrescu mentions a dispirited attitude which “thought that our city was condemned to an eternal and irreparable banality.” The idea of moving Romania’s capital from Bucharest either to Băneasa or to Brașov was also all over at the time. Dobrescu attributed this way of seeing things to a lack of preoccupation and “aptitude for city issues” and went on to implement his vision of the capital, which he saw as representative for the spirit of Romania which had been recently unified. “The city of Bucharest needs to be guided so as to be able to offer all the civilization that the spirit of our people can generate,” he explains.

One of the first measures that mayor Dobrescu took concerned the enlargement and straightening of the city’s streets. The arteries that involved works included Dudești Road, Colentina Road, Griviței Street, Rahovei Street, Văcărești Street and Pantelimon Road. The works entailed the overcoming of “a petty urbanism of the small and convoluted streets and markets, which make our city an anti-motorist one.”

The University Square and the Military Circle Square were modernized. In 1933, the mayor proposed revamping the Patriarchy Church and works kicked off despite opposition to the project. The works, which took two years, came with a discovery: the icon of the patron of the church, hidden beneath a rock laid in 1793.

Meanwhile, the first pools were set up for grownups, as well as sand basins for children and “communal fields” for sport. The Communal Museum was commisioned during his mandate, the predecessor of today’s Museum of the City of Bucharest. The project of the Bucharest Pinacotheca was born during the same time.

Mayor Dobrescu had the city’s green areas in mind as well, and the Snagov and Băneasa parks were set up. Public toilets were added, as well as an extended network of public fountains. Works were carried out on the Dâmbovița river, thus lowering the risk of infections coming from it. The river was covered in between Calea Victoriei and Șerban Vodă Bridge, and sewage works were undertaken at the outskirts of the city. Bucharest was starting to look like a Little Paris downtown but the attention given to the marginal areas marked a new stage in the transformation of the city. The Obor Central Halls, a building that is today on the list of the city’s historical monuments, were set up.

During his mandate communal canteens opened. These offered milk and fish lard for free. For the first time, the City Hall set up, at times of very low temperatures, steam cauldrons to help those on the streets keep warm. Free winter shelters for those without a home and canteens for the poor and for workers became available. Also in the area of social protection, the City Hall worked to identify poor families in need of help. A maternity opened, with the costs undertaken by the local authority.

The mayor directed his attention towards the cultural domain too and during his mandate, the Book Week was inaugurated.

The various nicknames that mayor Dobrescu received speak of his persistence, of the transformative actions he undertook, and of the resistance and mentalities he faced in implementing them. These varied from “the mayor of justice” or “the mayor of the slums” to “the pickaxe mayor” or “the finance of nonsense.”

The way Dobrescu evaluated his achievements offers the measure of his urbanistic vision. The mayor speaks of how the citizens of the capital began to love their city and how he managed to prove that urbanization means enrichment, not spending. Dobrescu left behind the vision of a Bucharest metropolis that its citizens care about. “The only obstacle in the way of the great Bucharest is still small Bucharest, which cannot make up its mind to make way for the great Bucharest because the great Bucharest asks for a great heart,” he explains.

Sources:

Pârvulescu, Ioana. Întoarcere în Bucureștiul Interbelic (Return to the Interwar Bucharest). Humanitas, București, 2003.

Hetel, Voicu. Dem I. Dobrescu primarul Micului Paris (Dem I. Dobrescu The Mayor of Little Paris), hetel.ro, 2012.

Dobrescu, Dem I. Viitorul Bucureștilor (The Future of Bucharest). Editura ziarului Tribuna Edilitară, 1934.

Şchiopu, Ana-Maria. Primarii buni ai Bucureştiului. „Bucur l-a lăsat sălaş/ Pake l-a făcut oraş/ Iar Dobrescu într-o năvală/ L-a făcut o Capitală” (Good Mayors of Bucharest. “Bucur left it a harbor/ Pake made it a city/ And Dobrescu in an instant/ Turned it into a Capital”), historia.ro.

Photo source: Galeriaportetelor.ro/MNIR