Chart of the week: Romania’s inflation rate to stabilise amid economic slowdown

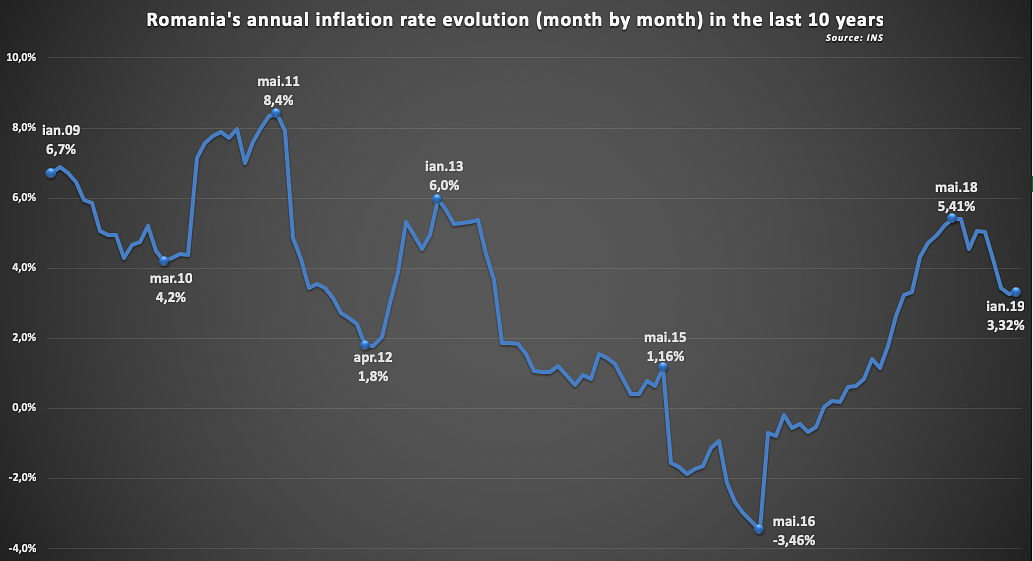

Romania’s annual inflation rate is expected to stabilize this year, after several years of rollercoaster-like evolutions. After negative inflation in 2015-2016, mainly due to tax cuts, the annual increase in consumer prices reached a peak in mid-2018. However, the economic slowdown is likely to keep inflation under control this year.

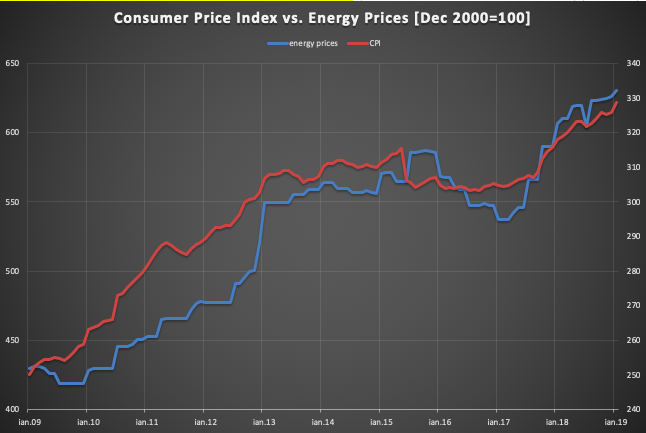

After the negative inflation episode in 2015-2016 prompted by external factors (the plunge in crude oil prices, quantitative easing programmes in both European Union and United States) as well as domestic tax cuts (VAT), the consumer price inflation in Romania accelerated, starting end-2016 to the peak at above 5% year-on-year in mid 2018, driven by domestic factors. These drivers were mainly on the demand side: households' disposable incomes (pushed up by administrative policies and tight labor market) as well as stronger consumer lending. There were also supply-side factors, though, such as the 15% rise of the energy prices (electricity, natural gas, heating) in one year (March 2017 to April 2018). Stronger demand for consumer goods pushed prices up, which reflected in the profit margins, profits and eventually in the "value added" generated by the trade sector. Toward the end of 2018, the inflation eased, helped by the energy (crude oil) prices, by the local currency's dynamics, and, to a large extent, by a change in expectations. In December, the headline inflation was 3.3%, and it remained close to the same level in January 2019.

The "core inflation" calculated by the central bank by filtering out the administered and volatile prices, has marginally exceeded 3% year-on-year in mid-2017 but has constantly eased since then to 2.5% in December 2018. This measure of the inflation is more under the control of the central bank, as opposed to the administered prices (regulated by independent bodies) or volatile prices (food, crude oil, driven by external markets or weather).

The inflation is among the macroeconomic indicators most frequently discussed by media and politicians, mainly because it has a direct impact on consumers. Take the recent "rising inflation that will eat into the wage rises pursued by the Government" allegations voiced by the opposition. Or the mutual accuses between Government and central bank about who creates more inflation: the Government by the fiscal stimulus or the central bank by loose monetary policy. Finding the meaning, the causes and the effects of the inflation gets often lost under such politicized context but can provide valuable insights.

Actual inflation fell behind projections in 2018

The annual inflation rate as of January 2019 is more than 1.4 percentage points below the median of the predictions made by CFA analysts in January 2018 (4.75%), and it is even lower than the central bank's projection. The inflation has accelerated during the first part of 2018, in line with the expectations, peaking at 5.4% year-on-year in May-June, but the disinflation was faster than expected toward the end of the year.

In June, CFA analysts were still predicting 5% inflation over a 12-month horizon. As of January, the analysts toned down expectations to 3.75% (median). The central bank projects 3.0% year-on-year inflation at the end of this year and expects annual inflation to remain below the upper bound of the target band by the end of the 8-quarter forecast period.

Inflationary drivers mostly on demand-side recently

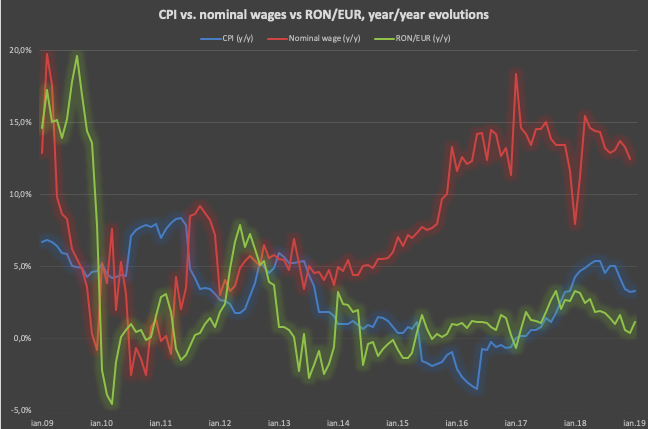

The primary inflationary drivers over the past years, as already outlined, were the households' incomes, consumer lending on the demand side and the energy prices on the supply side. On top of this, the inflationary expectations have constantly been the main driver, with an impact of the same magnitude as the combined effects of the other drivers.

The economy-wide net wage in 2018 increased by 13.1% year-on-year and the 12-month average annual rise remained in the double-digit rates region since April 2016. The latest wage data, dating December 2018, indicates no visible slowdown (+12.5% year-on-year) and January figures will bring further increase once the minimum statutory wage rises again. On the longer term, however, double-digit nominal wage growth rates are not consistent with the 2.5% inflation target. Even the Government's optimistic scenario envisages slowdown in wages' growth to 7% per annum in 2020-2022, after still robust 14.9% increase in 2019.

Separately, the volume of new consumer loans increased by 18.9% year-on-year in 2018, after a 5.6% advance in 2017. The annual rise accelerated to 35.5% y/y in the last quarter of 2018. The impact of the new, tighter, lending regulations and the "greed tax" on consumer lending remains unclear yet. However, annual growth rates of 35% are not sustainable.

Finally, the energy prices have been a significant driver of inflation over the past couple of years. After decreasing nominally in 2016, they rose by 7.7% in 2017 and 6.2% in 2018. The Government adopted measures aimed at capping energy prices (gas and electricity), starting March 2019, but this is likely to result in higher prices of consumer goods. Above all, expectations for slower growth have played a key role in shaping inflation over the past year. Independent projections put this year's growth around 3%, down from 4% in 2018 and 7% in 2017, meaning that the intensity of demand is sharply declining with the supply-side drivers (energy prices) and the exchange rate dynamics possibly taking over as the main drivers on the longer term.

Limitations of headline inflation

The consumer price inflation, the most popular measure of inflation, measures how fast the price of a basket of goods reflecting the consumption at national level, is rising. Or, how fast the value of the money is diminishing, again, measured in terms of the baskets of goods the money can buy. The problem is that the basket of goods reflecting the consumption at national level is an average of the individual baskets purchased by each household. And there is no such household like the average household.

Since the inequalities in Romania are the widest in Europe in terms of incomes (and not only), chances are household consume entirely different baskets of goods, and none of them overlaps to the average. Low-income households spend more on food; hence they "feel" higher inflation when the price of food is rising. There are no estimates for Romania's regional consumption, but data at European Union level show that the share of food goods in the consumer basket range from 10% in the UK to 39% in Northern Macedonia (it is 29% in Romania, roughly twice the 15% EU average). In principle, each household can define its inflation based on own consumption basket.

Furthermore, the consumption basket itself is changing in time and in some cases the changes are so dramatic that the goods purchased today can simply not be compared to those purchased a while ago (TV sets, mobile phones, cars, services, but also more common goods like some food goods, have changed significantly from one year to another). The rise in prices thus includes a change in the quality of the products (typically positive, but possibly toward lower quality goods at times of recession).

This also alters the comparison of prices among European countries as well, since the goods defined under the same name are simply different. Based on comparing the price of a (Dacia) car in Romania with that of a (BMW) car in Germany, Eurostat may come to the conclusion that prices are lower in Romania, which is not evident from the example. The heated debate related to double standards of same goods sold in Eastern and Western Europe is relevant in this regard, but it is instrumental along our line of reasoning to illustrate the limitations of the headline inflation concept for different categories of consumers in Europe, but also in the same country.

Furthermore, the consumer basket is not perfect since it sometimes fails to include goods that entered the market relatively recently, such as financial services for instance, which account for a large part of some households' budgets (namely those households that contracted a mortgage loan). The share of financial services as defined in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices for Romania is 0.06%, ten times less compared to nearly 0.6% in Bulgaria and 1.6% in Hungary for instance.

However, consumer price inflation (CPI inflation) is the best compromise for the practical purpose of measuring the prices in general. It is used to index wages, pension, other social benefits, claims in Court, and other monetary variables.

A national bank's primary goal is preserving price stability, but even ideally this does not mean constant prices. Certain inflation was found to be beneficial to growth, since it makes possible relative price cuts, meaning decreasing the price of some goods compared to the prices of the others, without actually cutting the nominal price (a move that was found to be avoided in practice). Romania's National Bank targets 2.5% annual inflation while accepting the index to hover within a +/-1 percentage point band. The 2.5% target inflation is rather high for a developed economy, but typical for an economy where significant relative price adjustments are still expected.

by Iulian Ernst, Editor Romania-Insider.com, iulian.ernst@romania-insider.com