Daniel Balanescu’s 2,200 green running men

A Romanian artist uses an ordinary pedestrian symbol, the little green man, to tell a story about the fragility of humans inside a system.

A long, long time ago, in a neighbourhood far, far away, two gangs crossed each other’s pass. The boys from the hood eyeballed the intruders, dismayed that they are not the only ones in the streets in that evening of the mid -’90s. The Bucharest homies had managed to take over the streets, and the neighbourhoods finally rang with the sound of rap music.

The provokers in that Bucharest neighbourhood called Dristor were a bunch of artists, who were planning a subversive action. Among them was a guy in his 20s, Daniel Balanescu, who was studying textiles at the Art University in Bucharest and had just discovered that the subway cards were thermosensitive, a discovery that would prove of lifelong importance for him.

The gangsta boys looked at the invaders, then looked away and decided not to make a mess. Artists continued their way, checked the doors of different blocks of flats - all closed, and then finally found one which was open. They silently got in, took out a bunch of drawings they had made before and papered the walls of the eight storeys with those drawings. At the main entrance, they put a big sign with the word EXHIBITION.

In the morning, people went outside to buy milk and discovered with bewilderment those drawings glued to the walls. Their block of flats was no place for such disrespectful things! There was an order in the universe that had to be regarded and works of art ought to stay in museums, not in a stairwell! What sort of a prank was going on?

“A lot of people are scared of art and consider it something elitist, aimed only for experts or for rich people. But this is so wrong! Outside of Romania, museums have free entrances and kids are encouraged to discuss about art. Creativity helps you develop harmoniously.”

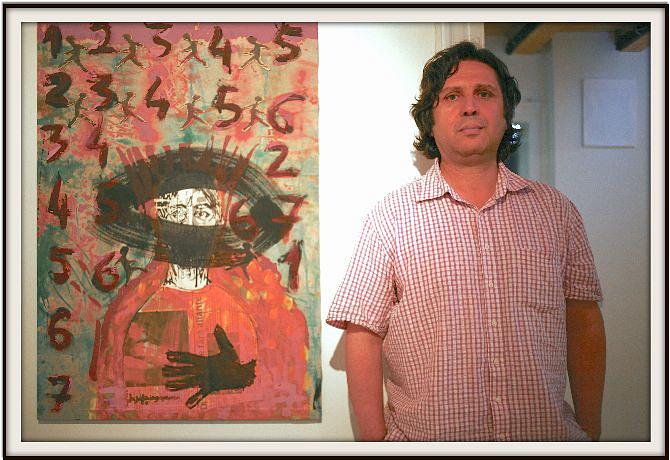

Sitting in the courtyard of the Aiurart gallery in Bucharest, two metro stations away from Dristor, and about twenty years after that exhibition, Daniel Balanescu explains how he sees art: unpretentiously, free to be interpreted, stemming from personal experience. Living now in Oxford, this soft-voice and friendly artist came back to the capital to exhibit here at the invitation of his long-time friends, Alex Radu and Irina Radu, the owners of the gallery.

The walls of this 19-th century house turned into an art space are papered now with various works of Daniel. They display over and over again The Running Man, an over-stylized little guy initially derived from the green pedestrian symbol. “Some years ago, I stopped at a zebra in Linz, Austria. When the green light flashed showing that I could safely cross the street, I saw the symbol and it was like this little man was telling me that it was ok to go on, to continue my way, that everything was ok.”

It soon turned into an obsession and the tiny guy, moving forward, running, or falling apart, invaded all his works. “It started as something simple, but I realised it can grow endlessly. So it became a work in progress. I drew this symbol in various situations: by himself, then part of a system, him against the others, him walking obediently. It came to symbolize the fragility of a person in a system.”

This was no abstract, made-up theme, but something that emerged from his experience. Daniel grew up in communism, a political system which sought to crush every individual will. “I lived for 22 years in communism and this leaves scars.” In one of his exhibited works, there are tens of little Running Men compliantly going in the same direction and only a few of them which try to go the opposite way, but they are collapsing and falling.

In another room of the gallery, there is a huge installation made of 2,200 metro cards, each of them displaying the little guy. If you get close you can notice that the 2,200 are all different, but from a certain distance it looks like the symbol was replicated over and over again. “The Bucharest metro card is similar to cards everywhere. It makes me think of globalisation and the levelling of society.”

Together with the Running Man, the metro cards represent one of Daniel’s obsessions which goes back to 1995, when these tickets were introduced in Bucharest. He was at some pub in Bucharest and his cigarette accidentally fell on a metro card. He then realised it was thermosensitive. “It was a happy accident, which made me aware that I could use the it as an art support.” He immediately drew the portrait of a friend using a cigarette butt. Daniel started working on metro cards with different pyrogravure instruments, or with cigarettes and lighters.

He was thrilled about discovering a new medium, but what really excited him was the possibility to involve other people in the project. Metro cards were no elite things, no gallery constrained instruments, they were cheap, ordinary objects which everybody had in their pockets and just threw away after using them. “I thought about asking others to take part in this, friends, friends of friends, unknown people. I asked them to give me their metro cards after they had drawn something on it. The fascinating thing is that on a train you can meet people of enormously different backgrounds.”

At that time there were about 400,000 people travelling by metro and Daniel thought that if only 10 percent would draw on these cards, they could paper the walls of an ugly metro station. “It would have been a collective portrait of the society back then.”

He was particularly impressed by some metro cards he received from a person. “There were three cards. On the first one there was Romania’s flag during the communism, on the second one Romania’s flag after ‘89, with the coat of arms of the RSR cut out, and then a flag of the European Union also cut out in the middle.” Some wrote shopping lists on the cards. Others wrote poems.

It’s easy to notice that Daniel likes mixing techniques and materials. Even as a kid, he didn’t just draw on papers, but he went straight to the walls of his room and covered them with drawings. “Hm...I should go back to that,” Daniel says laughing. In high school he drew a lot of cartoons of his teachers. But when he entered the artist adult life, things were less funny. “Money has always been a rather sensitive issue. It’s very difficult to make a living from art. You need to enter in a very good galleries’ circuit.” He has also worked as a costume and scenic painter in film and theatre. “It was something that I liked, but also a survival thing.”

Daniel now lives in Oxford, where he moved with his wife who does a master there. He works in a rather small studio and thinks it’s hard to get by there, because it’s a tough competition, but it’s also very nice. “If somebody likes your work, you’ll be contacted. I just received an invitation for a symposium in Germany.” He was also invited by the Oxford University to present his metro tickets project in a department there.

“Some of the drawings on the metro cards remain visible for years, other just fade away, just like in real life. There are many silhouettes which now can hardly be seen,” Daniel says. Then he adds: “I think that the conclusion of this project is that our lives are not that different from these metro cards. We all think that we have unlimited journeys, that we can travel endlessly, but we never know where it ends.”

But others may have a completely different understanding, he adds. “I like kids’ reactions a lot, they are so genuine. Yesterday a kid asked me ‘Hey, why are you drawing so many little guys?’ I told him that he was a little guy as well.” And he answered right away, ‘hey, but look at my dad, he’s also a little guy.’

……………………………………………………………………………………

You can visit Daniel Balanescu’s exhibition at Aiurart Gallery, Lirei 21, Bucharest, until June 20

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com