An American in Iași: A professor’s experience in late 1980s Romania

David Hadaller spent an academic year in Romania in the late 1980s as a Fulbright professor teaching literature and writing in Iași. He arrived in the country not expecting he would have to put up a struggle to be allowed to teach, learn to operate within a system of double-entendres or meet his wife. He kept a visual record of his time in Romania, which he shares, alongside photos taken in the country at later times, on a dedicated Facebook page. More on his experience below.

This exclusive Romania Insider article tells the story of an American professor who had the chance to experience life in communist Romania in the late '80s. A fascinating trip back in time (accompanied by photos from David Hadaller's personal archive) with a twist of humour and nostalgia. You can read this article and support us to write more such interviews by getting a Romania Insider membership. With our Premium membership, you will access all our exclusive articles and also get seven premium newsletters.

David Hadaller arrived in Romania in October 1987 to teach American literature and English at Alexandru Ioan Cuza University in Iași, in the northeastern part of the country. A flight that took off from Seattle took him to Los Angeles, then Frankfurt and eventually to Bucharest. He took the train from the Romanian capital to Iași a few days later, arriving in the city that would be his home for the following year.

At the time, Romania was experiencing days of deprivation following the austerity policy introduced by dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu in order to pay the country's external debt. Electricity, central heating, and running hot water were often turned off, and basic foodstuffs were rationed. In the apartment he was assigned in Tătărași, a neighbourhood of Iași, he would experience that first-hand, he explains, highlighting the immersive nature of the educational program. "That's the beauty of it, for an academic: I'm living day to day in Romania. I'm not a tourist for two weeks and go away. I'm there day in and day out, so I have to go through the snow, and the slush, and the sleet. In those days, I had to endure the lack of heat and hot water just like everybody else did. And that's the good thing, that's the great thing about an educational exchange. That's why I'm a true believer in the Fulbright program, which is why I'm delighted the Fulbright program has not only succeeded in Romania but flourished beyond anybody's dreams."

'It will change your life'

In 1985, while he was attending graduate school at Washington State University, working on his PhD, David Hadaller had a talk with his former professor Dr. Fran Polek, who had been the Fulbright lecturer in Timișoara from 1984 to 1985. He wanted to go to Europe to live and work, and Polek suggested applying for the Fulbright program. He told him: "David, it will change your life forever."

He finished the application in September 1986 and three months later learned that he had been accepted by the American side. His credentials were then sent for approval to the Romanian side. Once he received the ok from the American program, he enrolled in a Romanian language course at the University of California, Los Angeles. "For about eight weeks, I took a class there. There were only two of us in the Romanian course that year, so plenty of attention," he says of the course he graduated with nota zece (an A, top grade).

It was a period of preparation, with no feedback from the Romanian side, he recalls. "It wasn't really until the last week of September of 1987 that the Ministry of Education approved me. I was approved by the United States in December 1986-January 1987, so for nine full months, I had no word from the Romanian authorities to the Americans. Every week they would remind them - 'we have people waiting'."

At the time, there was one Fulbright post in Timișoara, one in Cluj, two in Bucharest, and one in Iași. As all of the others were staying for a second year, the only position open was the one in Iași. Still, even though he was the only candidate for the only position available, he didn't receive the approval of the Romanian Education Ministry until the end of September 1987. As a graduate student, he could afford to wait as he could always go back to his studies, unlike a professor who would have had to set a schedule in advance. He later learned that delaying the official recognition until after an American semester had begun was meant to discourage U.S. lecturers. "But I was a single guy; I didn't have a family so I could wait them out. […] It was a year-long process. And of course, it needn't have been, but it was."

And so his Romanian experience started. "It's hard to convey what kind of society I walked into in those days. For an American graduate student at the university - everything is available to them. We weren't rich, we were genteel grad students, but at any time of the day, I could go order a pizza, get a beer, and buy really anything. I didn't have much money, but it was available. Then I went into a society where none of that was available," he explains. "But I also have to add I was a very privileged person in that culture. Because I did have an apartment, I didn't have to stay there; I could leave Romania anytime I wanted to - Romanian citizens couldn't do that. So I had a very privileged existence there. I'm not complaining about that; in fact, I'm glad I've had it. This has worked pretty well for me, I met the love of my life. It was an accident, but it happened. Something I was not looking for."

The missing students

By mid-October 1987, he had arrived in Iași. Exhausted from the trip but pleased to be in the country, he imagined he would start teaching right away. But on his first day at the university, he learned, to his dismay, that it would not be the case. The students had been sent to do cafeteria duty, he was told in a conversation with another professor, while being assured that this happens sometimes.

"My reaction was stunned disbelief; my face must have looked pretty surprised. And I said: 'There're no students today? None?' And he said: 'No, no students today. We'll see if we can arrange something.' This was like the 17th of October. And I'm thinking, wait a minute, the semester has already started; what's going on here?"

He had assumed that, as it happened in the U.S., another professor would cover his courses until his arrival, but, as it turned out, there were no courses or students.

"On my way home, I remember this walk from Copou Hill all the way back down the tram line to Tătărași, I had a nice, long, thought-walk, and, by the time I got back to my apartment, I was really angry. It was like two, three in the afternoon. First thing I did was call up the embassy 'Get me a ticket out of here. I'm not going to spend any time here. I came 5,000 miles, 7,000 miles from Seattle, and they won't even introduce me to students. I've met nobody here; what is going on?'"

After the embassy's cultural attaché called the head of the department in Iași, he got back to him to report he was told David was overreacting and students were, in fact, waiting for him, but he had just not been there on time. "From day one, I was getting what I call the system, which was everything I said was wrong. When I had a complaint to the embassy about the administration at the university and my job, they would turn it around as my misunderstanding and my problem."

From October to December, he had six hours of student contact, he explains. "Not six hours a week, six hours for three months." After a call to the university rector and four and a half months after arriving in Iași, he finally had classes. It was February 16th, 1988.

"I'm trying to communicate the utter frustration I felt not because of the living situation, not because of food or water or anything else, but because they would not let me teach. For an academic, that's what we're in it for; we're in it to teach literature. Now, I'm teaching Hemingway and Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Huckleberry Finn - it's not political; in fact, it's critical of America."

Teaching at last

From February on, Hadaller had four groups of students. He was teaching Composition English and Writing to a first-year group. The second-year class was focused on American literature and writing essays. He was also teaching the American Novel to a third-year class and a course on literature in English by women to students who were about to graduate. The American Novel included Hadaller's focus, the novelist William Styron – he published in 1996 the book Gynicide: Women in the Novels of William Styron.

The students inspired him to work with the system, he says, so he would be teaching the following semester as well. "The students were really good," he explains. "It was freezing cold in the classroom, and they would come – I've never seen this in an American university – and they were wearing gloves with finger holes in them so they could write and have their hands warm."

None of the courses he delivered was for credit, so the students didn't receive a grade for work in the course. He felt it was another insult since, as a professional he should have been able to evaluate his students, but by February he was simply grateful to be teaching, and the grading issue didn't seem that important. He was more focused on working with students he saw were held back by a flawed system.

"I walked away from that experience feeling like I was the one that learned a lot because I saw an entire generation of young people as undergraduates, great minds, and they were being held back, literally, by this system. If only I could have had them back in October, I could have improved their writing skills even more."

Life in communist Romania

The first months in the country were a period of adjusting, exploring the surroundings, and learning the ropes of the system.

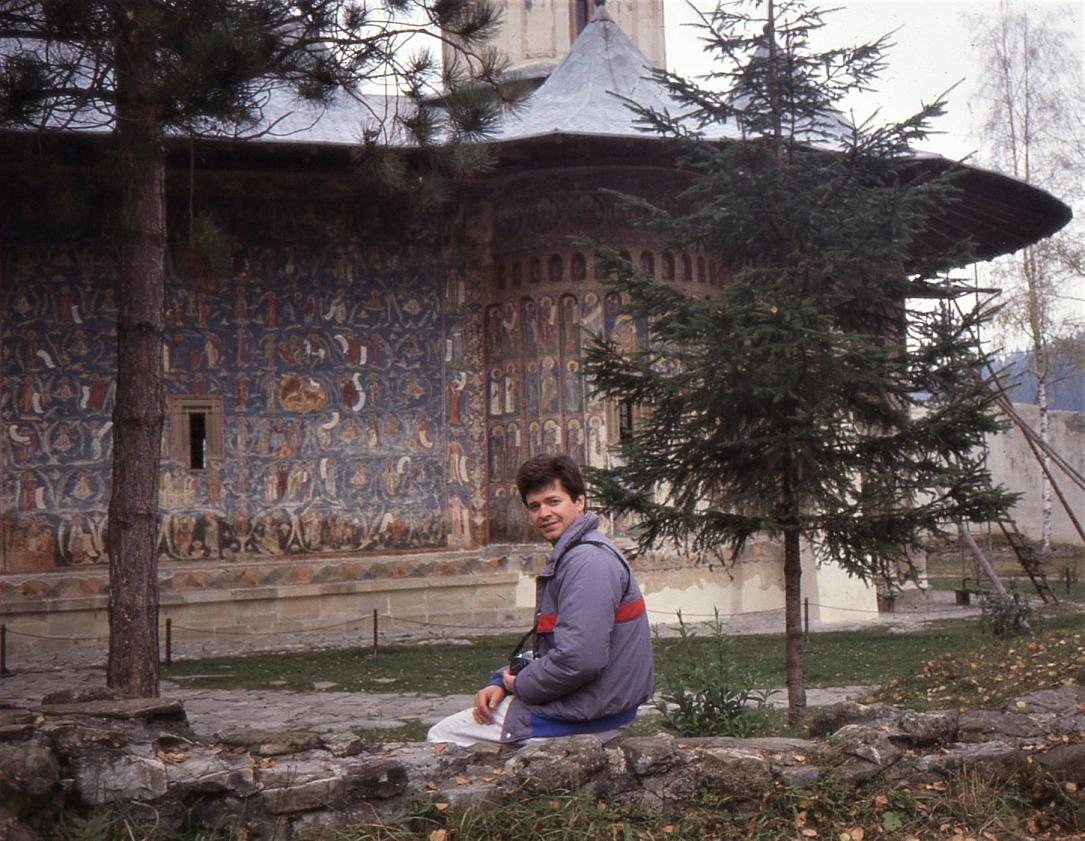

He took frequent trips to Bucharest, but also to the tourist places on Prahova Valley, Predeal or Bran, and joined two American art teachers from the University of Minnesota on a tour of the churches of Moldavia. "If it weren't for that particular trip, I would have never gotten to see Voronet, Agapia. […] When I went there and saw these beautiful churches and the pine trees and everything, I thought, 'Ok, calm down David, this is a beautiful country; the bureaucracy is everywhere.' So, Romanian people saved Romania once again."

The trips to Bucharest were occasions to get acquainted with the city and its international community but also to bring back various things for friends and colleagues in Iași. He was receiving a salary in Romanian lei, but there wasn't that much to buy in local stores. "I remember there were canned sardines, but I don't like canned sardines, but I would buy some for my guests." He also had deliveries from Casa de Comerț, a communist-era delivery service that Romanians could also phone to order goods they would not have found in stores. "They would come once a week or every two weeks and drop off some food. Every time they gave me like 36 eggs; I was a single guy, there's no way I'm going to eat that much, so I would give them to my neighbors. I remember the first day I gave them to the Constantinescu family next door - she wanted to pay me for it," he recalls. While in Bucharest, he got a card that allowed him to shop at the diplomatic store, open to the city's international community; there were also the "dollar shops," where the payment was made in the U.S. currency, and Peter Justesen, a Danish delivery service. "I was very privileged; I could always go to a dollar shop, eating was never a problem for me."

And while he always tried to buy things for his friends and colleagues, he also had to tread carefully as they had to report all interactions. "Compared to my colleagues, university professors, I had a lot wider access to food and certainly to travel. I tried to do everything I could, get books for them and so on. But like I said, everything I did or gave, they had to report. And I didn't want to make their lives more difficult."

The system was distrustful of its citizens and foreigners alike, and the encounters between the two cultures were under close watch.

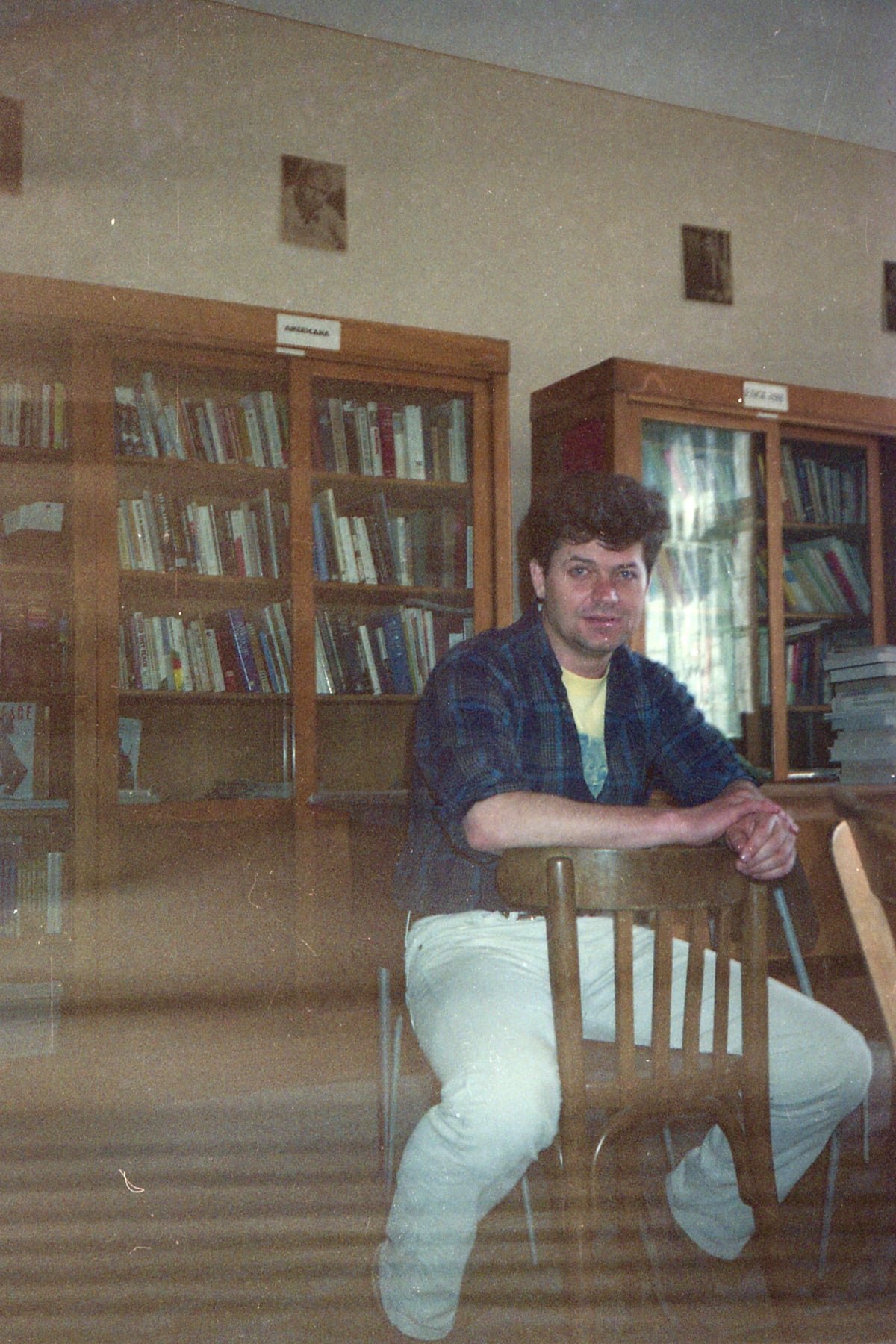

The newspapers and magazines that arrived at the university's American reading room had to stand the censorship reading. "Every three-four weeks, there would be a car from the embassy that would drop off newspapers and magazines for the American reading room. All of these things had to be censored; they never let a Time magazine go right in. Their excuse was that they were going to steal it […] but, of course, because they had articles about Ceaușescu in there. We had to give all the newspapers and all the magazines to the head of the department who would then, I guess, give them to the local Securitate. They would read them; they would usually give them back six weeks after they had gotten them, so the news was already old by that time. It was just old magazines in there."

Similarly, he was not supposed to teach his students in the American reading room, only in the classroom, but the term 'teaching' actually covered any interaction with the students. "What do you mean teaching? They asked me – 'Mark Twain, where did he live? Well, he lived in Hannibal, Missouri.' Is that teaching? You see how ridiculous this was?"

But, after returning from the winter holiday, he felt more accustomed to the environment. "The first two months, it was me adjusting. But when I came back in January of '88, I was adjusted. I knew what to do. I was ready to teach, I was ready to live, I was ready to go."

A Romanian family

Only a few months later, he would meet his wife, Mirela. It was April of 1988, and his wife remembers him acting as if he had been in the country for years, not just a few months. He attributes this to having gotten to know the city of Iași by then and being happy to teach.

The two first met when Mirela, already a teacher, attended a lecture on Faulkner that David was giving. She walked in late, prompting David to make a joke he usually employed when dealing with unpunctual students. "I say 'There's always has to be somebody who's late. And you know why that is? Because she needs the attention.' And she was very embarrassed; her face was red. I said: 'I'm sorry, I don't want to embarrass you.' That's why she didn't like me at first."

A year later, they were engaged, all the while doing a "very delicate balancing act," he explains. As they were supposed to, they filled out a petition requesting permission to marry. After leaving Romania in June 1988, he returned in May 1989, and the two got engaged, preparing for a rather lengthy wait when the Revolution of 1989 happened. By March 1990, he was back in Romania, and they got married. A religious ceremony followed in Seattle in June of the same year. They lived for a while in New Mexico and in 1992 moved to New York, where they've been living ever since.

A few years ago, the story of how they met even won Mirela a prize at a local radio station which invited listeners to call in for Valentine's Day and tell how they met their significant other.

They have another Romania trip planned for this summer, after a pandemic-induced break, this time for their son's David wedding in Constanța. David is getting married to a woman who, even though she grew up in New York, was born in Bucharest. Her parents are Romanian, and they moved to New York, where the couple met. Their other son, Nick, is "pretty much a New Yorker, but he speaks Romanian and Macedonian pretty well."

A photographic recollection of Romania

For several years, David Hadaller has been updating the Facebook page My Fulbright Year in Romania, where he shares photos of Iași or Bucharest as captured during the time he spent teaching in the country, but also ones taken shortly after the 1989 Revolution and later, and tidbits of life under communism. The images also reveal the capital city scarred by the events of December 1989, or the seaside city of Constanța in early 1990, as well as other tourist spots in the country.

Taking pictures started as an activity meant to support David's teaching. Before leaving for Romania, he decided he should learn how to take photos as he was about to live in an entirely different part of the world. First, he took pictures of America to show to his Romanian students. "They would see new photos of what America looks like today, in 87. I was going to use the slides to show my students," he explains. Using a Vivitar camera and later a Pentax, he took photos of various historical hotspots: Walden Pond – for when he would read Henry David Thoreau with the students, Concord, Massachusetts - where Ralph Waldo Emerson lived, Plymouth Rock – the site of disembarkation of William Bradford and the Mayflower pilgrims, and various spots in California.

But the photos that got the most interest from the students were not the ones he had expected. "Some of the photos that really got their attention were the ones where there were pictures of cars and advertisements. Not of scenery. They wanted to see what the Americans were doing because their view of America was through TV movies, basically. They would ask: 'What kind of car is that?' Which is natural, they're 19-20-year-old people in Iași, and this guy's from America."

He also recorded two hours of MTV on a cassette, and whenever people came over to his apartment he would play it. "It was two hours of MTV with all the commercials. The thing that got the attention was the commercials. Because, what kind of television did they have in 1987?"

Similarly, while in Romania, he took photos to show to his students in the States. "I would walk from the university to my apartment every day, twice a day at least, along that route, and in my mind, I'm setting up the photographs for when I'm actually carrying my camera. I took photos of my route to the university and around the sights in Iași. And in Bucharest too."

While taking the photos in Romania, he feared his camera would be confiscated. "That was my worst fear. My thinking was, if I take these pictures out of Romania, I'm lucky." As he couldn't develop it in the country, he used the diplomatic pouch to send the film to England. He did have three film rolls confiscated in the Otopeni airport when he left for London in December 1987, but the photos eventually made it out of Romania. "I was surprised, when I put my photos up, at how many people were clicking on them. But I shouldn't have been because not many people were taking color slide quality photos in '87 – '88 in Iași at all."

A surprising year

Looking back on the time spent in the country, there are several things he didn't expect would happen. He didn't think he would meet his wife here. "Whenever you're trying to do something, it doesn't happen that way, especially in terms of love. But I was not looking for a wife, certainly."

Professionally, the challenges made him even more dedicated. "It really did, once I got over my anger and I settled down because of the people, because of the students." The experience also taught him a lot about himself and how he would react in a different culture. "I'm happy to say, for the most part, I did pretty well adjusting," he says, highlighting that he learned to operate within the system, which meant saying one thing and doing the other, all with a view to protecting his colleagues and dear ones.

"I learned how to say things and then do the opposite. I never had that problem in an American university. It's a crazy thing. I learned how to talk in three different ways – it was how to talk to the director of the English department so he doesn't get in trouble, so he could say the rector or the Securitate, well, the American told me he wasn't teaching, so he's out of the hook. It's funny […] everything almost was a double entendre; it had two or three meanings. I was not used to that. I didn't get used to it, I learned how to operate that way so that my colleagues wouldn't be threatened in any way, and my wife wouldn't be threatened."

Although he was up for reappointment, his Fulbright term was not renewed the following year. The woman who replaced him in 1988 lasted a month, and there was no Fulbright professor in Iași from November 1988 until September 1989. But the connection with the country had been forged already. "My story, when we talk about Romania and me, it's all personal now. Romania isn't like a country or a society, it's my family. I'm an American but, to use the metaphor of weaving, my life in the last 30-40 years has been woven with Romania so much."

Opening photo: David Hadaller in Voroneț in October 1987. All photos © David Hadaller

simona@romania-insider.com