Eduard Kunz - Just another Russian space conqueror?

Pianist, actually. Living in Bucharest.

In a Siberian city called Omsk, at the end of the ‘80s, a mom would tell her son, Eduard Kunz, “sweetie, why don't you go to the bakery, just pop in and buy some dough for pelmeni?” The trip to the bakery meant a 20 minutes walk to the bus station, a 45 minutes drive to the bakery and back, so the whole 'popping in' would take Eduard 2 hours. But it never seemed long and that was what it was; no complaining and no hard feelings against time. The patience to do things was still there for everybody, but it soon got flushed away down the rush of history. Eduard Kunz somehow managed to remain comfortable with time.

It's past 7 PM, on a Wednesday evening, beginning of January, and I'm desperately standing in front of the locked door of a building near the Cismigiu Park, in Bucharest. I should have already started the interview with the 33-old world renown pianist Eduard Kunz, but I forgot the building code. As a young girl is approaching and she seems to be living there, I ask her if she happens to know where the pianist Eduard Kunz lives. "Come in," she answers in a very comforting, confident way. "I'm Diana Kunz, his wife."

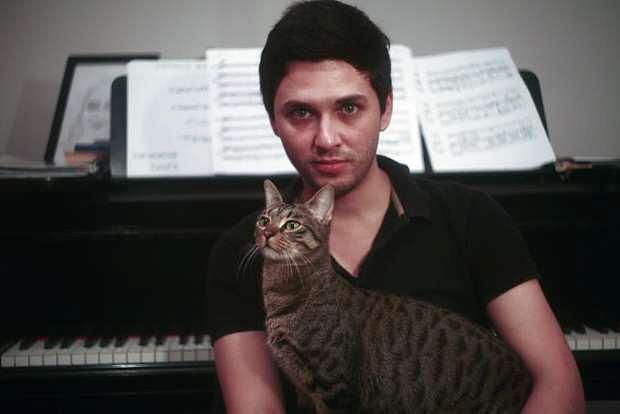

On a quick Google Search, you will find out that Eduard Kunz was named among ten tomorrow's great pianists by the BBC Music Magazine, took part in several prestigious competitions and won many prizes. I kind of expected to meet a solemn man, straight in his chair, talking with great patience about music and life. But in the main hall, there was this barefoot man who seems very young, not formal at all, talking in Russian to a little girl, his daughter.

Persistence

"In the Soviet Union there wasn't that much you could acquire, but, surprisingly enough, I am sure that every second family would have a piano as a piece of furniture. I started to play piano at my grandmother's house when I was 5 and a half. She could play piano, a little bit."

The interview takes place in the room with the piano and Eduard moves a lot while talking. He remembers a thing, suddenly gets up and just as abruptly he sits down on his chair again. Impatient as he seems, he's the same person who for at least 20 years has rehearsed almost daily for hours and hours.

Eduard, the kid, was helped to be persistent by his mom. "My mom was already single, she already decided she would dedicate her life to me and we started to go to competitions. I guess she believed. It's one of those things, you believe and then it happens." And when the kid turned into a teenager, rehearsing was already a habit and there was no danger to desert. "It's like running. The first day you want to kill yourself, but you get used to things."

"Of course my mom was helping me to be persistent, but from where I come from, it was this idea to achieve things, and particularly to achieve things through struggling. It had to be difficult. You have to want, my mom was telling me. And believe me, to kids like me, the parents would say exactly the same thing. There was only gymnastics, or only piano, one thing only."

Eduard warns me from the beginning. "I'm telling you, such a difficult profession! Don't do it."

No clear path

The path was never clear. "While studying at the special school for music in Moscow, most of the kids came from musical families and knew exactly what they were doing. My mom wasn’t like that. I guess she sort of had a dream or whatever. But from where she comes from, a concert pianist would be something in the zone of space conquerors, or some profession that no one knows how to go there, where to go to."

After winning the third prize at a national competition, the 13-year old Eduard moved to Moscow with his mom. "My mom did an absolutely heroic thing. You have to understand what moving to Moscow is. There are 3,000 kilometres from Omsk to Moscow. That’s 44 hours on a train. Before moving there we had no plans of any flats or houses."

The competition in Moscow was huge, but there was not anything sick or twisted. "We were normal people, but very motivated in what we did. Another factor is that 99.9, if not 100 percent, were poor, except for some kids who came from superstar musicians families. And poor is very good, especially when you are young, because it makes you want."

Moscow was followed by Cambridge, then various cities in England, and now Bucharest. "At the time it was not clear what to do next. Even now it's still not clear. I'm not lying to you: 150 concerts a season, that's a big career. But that's one side. The second side is that if I get there it means spending about 300 days in hotels. I have about 60 concerts a season now, which translates into 3, 4 months out of 12 far away for home. It's never being with your family, never being with your kids. Over the last 20 years I've been in a way an immigrant. It’s lonely, you speak different languages. Of course, one could stay in one place all his life. No one will tell you what's best."

"There is this pianist considered by many probably the greatest living pianist, Grigory Sokolov. I went to his concerts. He has absolutely nothing in his life apart from this. He practices 10-12 hours a day, he only talks about this. It’s 100 percent dedication. For every concert he needs 7 hours to rehearse. It's very specific. I've been like this until very recently. It's one thing only and you are persistent."

Then he pauses. "But then you have a child. And you are not alone anymore."

Music

"Did you ever feel at a certain point that music was taking over your life?" I ask him. "Yes, of course," he answers straightforward. Eduard Kunz is never playing the lost-in-the-cloud-artist and he won't let himself dragged into any mystique about how the artist is covered with emotion every time he rehearses. "It's called professionalism. That's what I have been doing for a living, in the last 20 years. It's the same for an actor; he cries on the stage- professionalism.”

Eduard Kunz continues very down-to-earth. “If you're not free with your means, your language, you can't express yourself properly. Emotion is important, at the end, but you need to get there, you need to be able to formulate it out loud, to make the performance as expressive as you want. There is so much work which takes your head rather than you heart. It’s like going to a restaurant with an amazing chef. He gives you the dish and it's magic and you don't see the process behind. But it’s just timing and discipline and onions and whatever.”

"But there are things which cannot be rehearsed and only happen on the stage. On the stage there isn’t only you and the piano, it's also the public, and it's as important as you and the piano. That's why I'm so against studio recordings. When I play, I can hear a thousand people breathing and they can't lie to me. People ask where are the audiences better. There is no such thing. Every musician who has been in one city, two times in a row, experiences a different city every time."

“So, what's the great deal about Music?” I ask Eduard. As a pianist concert and a professional musician, he should understand a little better what makes music so important in our lives.

He hesitates no moment in answering. "It's very simple. All the genius music is about one thing only. One thing only. Love. Nothing else is there. If you take something really great, believe me, there is no other subject for a really great piece of art, music, painting, for anything humanity created. The greatest thing is about love."

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com

(photo by Diana Mesesan, illustrations by Alexandra Gavrila)