How to heal covert scars for half of your life: Top Romanian model about his secret to success

Having learnt how to be tough as a child in the concrete jungle, Gilbert has nothing but appreciation for his childhood environment: "Yes, back then, Petre Ispirescu [Street] was ruled by the law of the jungle, but I was lucky enough to grow up in a family that highly valued being Roma. My grandma, Florica, always advised me not to lie and to work hard, so it was easy for me to implement and follow all these values," he remembers. Gilbert wears a short-sleeved shirt with a Mona Lisa pattern. His left arm carries the hard-to-miss display of a tattoo, showing broken knuckles and blood.

Now, he is 35. Eighteen years after he left Romania and after almost as much time spent on self-development, Gilbert says he finally came to understand his inner conflicts: "I thought I was going to conquer Spain, the United States, or even the world, but my story is actually about conquering my inner demons, my own perspective, to come to peace with who I am," he adds.

One of the most impactful moments in Gilbert's childhood was when his parents divorced. He talks about it as a trauma in Gelu Duminică's podcast, but now he remembers it slightly differently: "When I was 10, my parents separated, and I felt a strong ambition to make my mother happy, to be the best, in school, in football, and then, in fashion. You can imagine that my family was not rich. I remember vividly how happy I was when mum bought me a pair of Nike football shoes because we hadn't had the money for [brands like] Nike. But small things like this are huge for a kid because they push you towards your goals," he says.

Now a personal coach among his other trades, Gilbert has had a turning point in his life when he prioritized finding answers to his questions. These questions were revealed slowly in his teenage years when he saw the impact of communism on his family. "They seemed to be in a box mentally, and, maybe, since children have more freedom, I allowed myself to ask, 'What's the difference between us and the rest?'" Gilbert remembers. He constantly had this question in mind throughout his seven years in Spain, where he started modelling and acting professionally.

All until one day in New York: "I met this guy; he and his brother owned a USD 10 million company while taking the metro, carrying a backpack, and wearing cheaper clothes than I did. In Romania, when I started working with [Cătălin] Botezatu, I was going out in Dorobanți [e.n area of Bucharest], and there was this 'rich kid' driving a Rolls Royce and smoking a cigar," Gilbert says, laughing. He thinks the contrast between the two stories is, in fact, a combination of ignorance and indifference: "The difference between most millionaires outside and inside Romania is the access to information. While some know they must wake up early and work hard, the others will never get out of their box," he adds.

While he does not believe that Romanians have a sense of their identity, Gilbert likes to reference back to some of the most popular characteristics attributed by Romanians to Romanians. "We are great with sarcasm, with irony, but we don't realize those are just a mask for something deeper," he says. Remembering times when he was talking about personal development and growth to his friends back home, Gilbert's words were not received with an open mind: "They were either talking behind my back or with irony, because it is much easier to have this reaction, than to start working on yourself," he adds. Tracing back the path to find out why Romanians developed such defense mechanisms, Gilbert proposes a theory.

He mentions Lise Bourbeau's book, where the author stated five wounds left from generation to generation in our minds: rejection, abandonment, humiliation, betrayal and injustice. "Think that many people did not have a voice for ages, women have only recently been allowed to vote, Romanians were vassals to the Ottomans for centuries, and Romani people were held as slaves for 500 years, but history books barely mention this!" Gilbert exclaims. He thinks that Romanians struggle the most with betrayal, being lied to countless times, but if they start focusing on one thing only, the country can move forward. "In my opinion, the primary way to heal this wound is to trust one another. We have resources; we have a great country, a great geopolitical position. If we were to be united, have good governance, and be able to keep the smart ones in the country, we could easily be in the top 5-10 countries in Europe," Gilbert adds.

To accept these generational and cultural wounds, Gilbert Costache talks about his experience of going through the five steps of overcoming trauma: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. "I do not think we, as the Romanian people, have even reached the third step, bargaining. We like to have a 'correct' barbeque, a 'correct' spritz and banter, and as was the example with my friends earlier, those people would rather deny the truth," Gilbert thinks. Being a Roma ethnic has also raised a lot of questions, but, step by step, he found some answers: "As Afro-Americans have created jazz, blues or rap, Romas have lăutărească as our mourning music. We like to cry and, sometimes, accept we went through hard times," he confesses.

Returning to Gilbert's opinion about national identity, sometimes he wishes he would encounter more people proudly saying, "I am Romanian!". "I always lived thinking I am just Roma. However, after doing a DNA analysis, I discovered I have Turkish, Greek, or Spanish blood, among 16% of genes tracing back to India. That's probably my Roma blood," he says, laughing. What he understood from this experience is that living successfully as a culture is not the same as identifying with an ethnicity: "I am a mix, and I believe we are all a mix of people nowadays, but above all, I am Romanian. And one may think, 'What does it mean to be Romanian? To be white? To be blonde?'" he asks rhetorically.

When faced with discrimination towards his background and the perception that "Roma people are simply bad people", Gilbert has articulated in time a few educated answers, backed up by Ana Maria Ciobanu's research in Obiceiul Pământului. Firstly, he mentions that the marginalization and segregation that started with the Roma slavery are still not appropriately addressed: "You still hear questions as an estate agent such as 'Are there g*psies living here?'. If you answer 'Yes', then people would refuse to move in. These are repressed emotions, haunting people for hundreds of years, and, in the end, this hate comes from a fundamental characteristic of the ego, that of wanting to feel more special than others," he says.

Gilbert mentions other countries that were built as a collective work of several nations, cultures and ethnicities, such as the US or Australia, where the road towards acceptance seems to get shorter. "The more people searching for, and accepting the truth, the quicker this process will be. Romania today, whether some like it or not, is the product of all of us, including Germans, Hungarians and so on. And when this acceptance happens, Romas will change too," he confesses. Finally, Gilbert addresses a more tangible example, that of the people from Cluj, feeling that their city is better than Bucharest: "They did not heal their wounds either. Yes, Cluj is cool; I love it! But when you think you are greater than someone else, you have yet to accept. And the first step is to investigate your past," he adds, looking slightly worried.

Coming back to the present day, Gilbert is on holiday in Puerto Rico and, possibly, his pixelated Mona Lisa shirt stands as a metaphor for his confusing past and the process of getting where he is now. When asked what success means for him, he moves up the couch and suddenly becomes more serious. Gilbert first mentions a theory describing life balance as a combination of relationships, with you, with money, career, friends and family, as well as romantic relationships. "Success means to be balanced and fulfilled, contento from Spanish. Reconciled. If you can find enough time for all those relationships, you reach success," Gilbert concludes.

by Ștefan Paiu, features writer

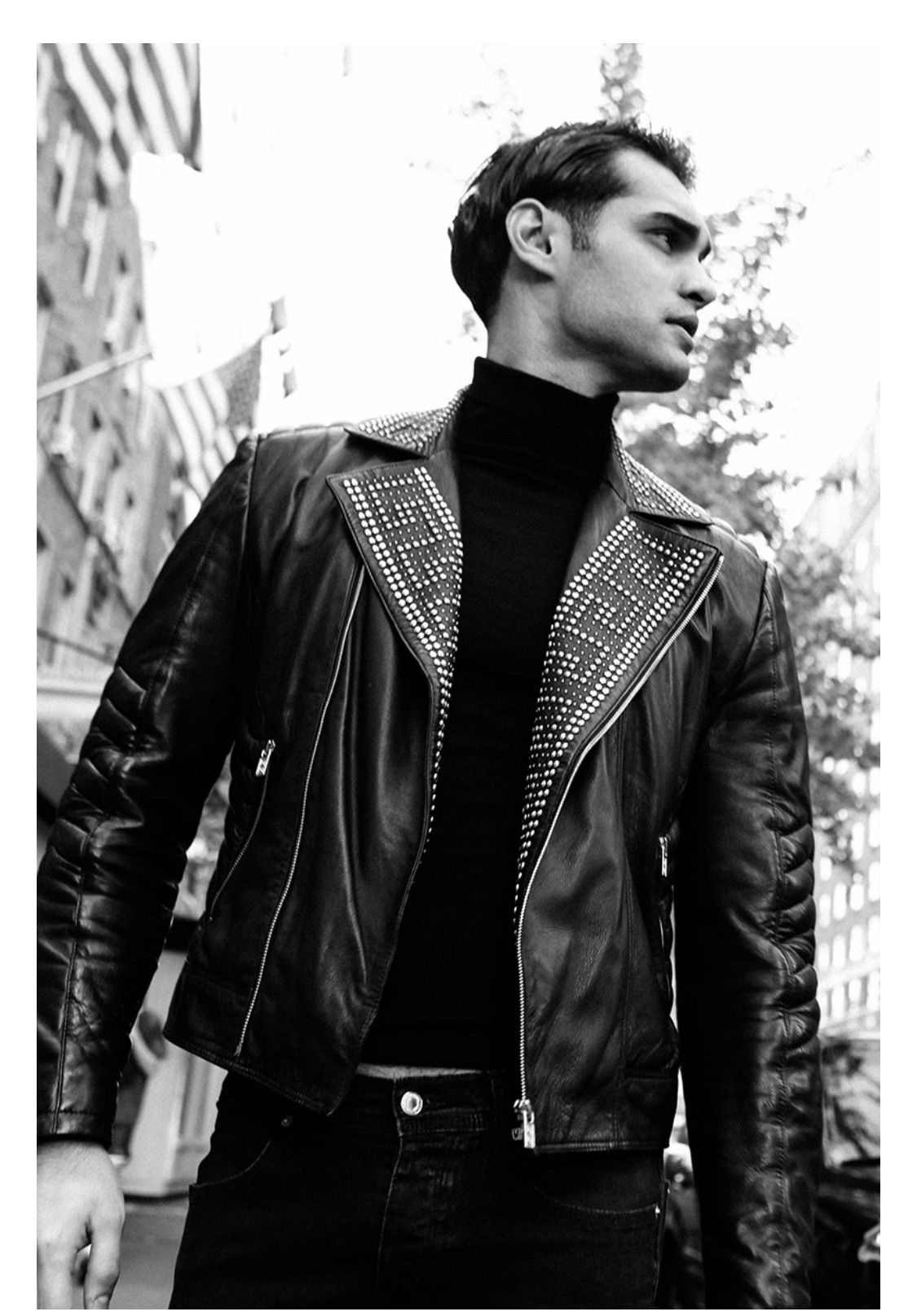

(Photos courtesy of Gilbert Costache)