Into the wild in the middle of Bucharest: the challenges of the Botanical Garden

How the Botanical Garden in Bucharest has managed to survive financial dire straits, intrusive visitors and even bombardments, but still struggles to find its path.

A girl wearing a hoodie and colorful trousers rakes up fallen leaves and weeds. She has a serious face, immersed in the music she’s listening to on her headphones. She does her job very rigorously. A few meters away, some boys carry big baskets full of dried branches, leaves, and weeds.

You can see them as you drive down the Cotroceni road. On one side of the street there is the Cotroceni Palace, the headquarters of Romania’s president. On the other side, stretching over 17.5 ha, the Botanical Garden. It usually looks empty, but now it’s in a frenzy of people and movement.

It’s early April, and more than 200 volunteers have gathered for the weekend to do the spring cleaning in the Botanical Garden in Bucharest. Volunteers have been doing this every spring for the last ten years They move across the garden, with scissors and rakes, leaving behind long stretches of green grass. Most of them are high school and university students, but you can also bump into people in their 40s and 50s raking up, cutting underbrush or picking up leaves.

In a strange coincidence, their volunteering day also marks an event from 71 years ago. On April 4, 1944, Anglo-American bombs hit the Garden. The ravages were significant: 500,000 of the 700,000 sheets of the Botanical Garden’s herbarium were destroyed. Apart from that, there is no memory of the war. In nature, history wounds heal the quickest. Another spring, and everything is new.

The beginnings

The Botanical Garden’s history starts with a fire and a tireless and romantic scientist with side whiskers: Dimitrie Brandza. In 1874, the young botanist, only 28, but having already studied and taught in Paris and Iasi, moves to Bucharest to teach at the Department of Natural Science at the University of Bucharest.

Ambitious and driven by his passion for plants, he gets the right to create a botanical department at the Natural Science Museum “Grigore Antipa” in Bucharest. But in only two years, in 1884, a fire destroys his entire plant collection. However, this makes room for a more ambitious plan.

With funds from the Government, Brandza sets up a new Botanical Garden in Bucharest, in the Cotroceni area. The Garden finally opens in 1891, after the greenhouses are ready. Bucharest has a beautiful botanical garden, but its founder has little time left to enjoy it. Four years after the opening, Dimitrie Brandza dies at only 49.

The misunderstood garden

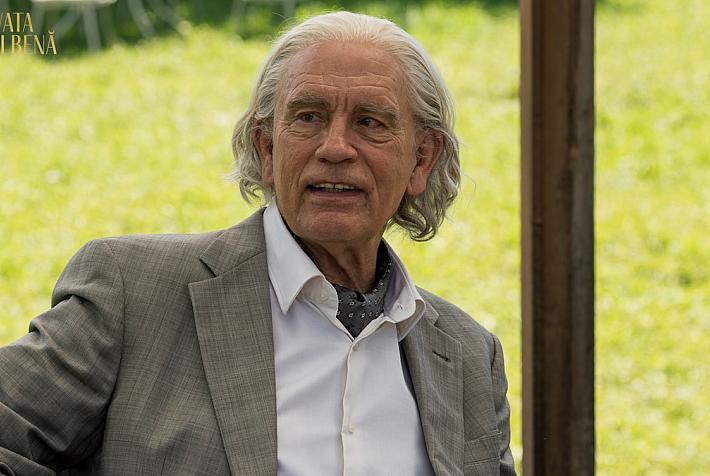

“A lot of people come here expecting to find a park,” says Paulina Anastasiu, the Botanical Garden’s director. “But we do have a lot of public parks. This is an institution of research and education.”

We meet on a windy, cloudy day, when the Botanical garden is empty, except for the employees. Paulina, in her not so glamorous office, but with an exceptional view to all the wild greenery overflowing outside the windows, seems a bit cautious. She manages this 17.5 ha institution, and she has to do it with very little money.

The Bucharest Botanical Garden is part of the Faculty of Biology, at the University of Bucharest. A quarter of its revenues come from entrance tickets, and the rest, from the state.

Some of the visitors don’t seem to understand the Botanical Garden’s function, Paulina says. They use it as a park, where unsupervised kids climb the tiny hills, step on flowers, play with the ball. “Take the Dobrogea hills- from a decorative perspective, maybe they’re not very interesting, but from a scientific point of view, we have some very interesting species there.”

However, all the foreign visitors are fascinated by a certain wilderness the Botanical Garden still has, she says. “They recommend us to keep it like this, because these things have disappeared from Europe.”

Into the wild

As you reach the Garden’s coniferous area, you seem to leave the city, step by step. The Cotroceni Palace is only some ten meters away, with its busy road. But the birds chirping and the long, deep shadows send you to the middle of a forest, on a distant mountain. You notice the swamp cypresses, with their strange cypress knees, a sort of surface roots which help in the tree’s oxygenation and assist in anchoring the tree in the soft, muddy soil.

Some pheasants may cross your path, as you move away from the forest and approach the greenhouses. The Garden has over 50 species of birds. The pheasants are most eye- catching, but there are several smaller species, which live here, enjoying the garden’s wilderness.

“We want to keep it natural and wild, but we don’t want it to look deserted,” says Paulina. Depending on the beholder’s eye, the Botanical Garden may seem wild and natural, or somehow unattended, in a fragile state in-between.

“University botanical gardens have the same problems everywhere in Europe,” says Paulina. In other countries, however, local communities get involved much more and support these gardens. In Germany, they have various associations such as the “Botanical Garden’s friends”.

Endangered beauty and the man with a PhD in roses

Marius Negulici is a garden engineer and has a PhD in roses. He is in charge of the roses, irises and Italian garden sectors and runs maintenance, cuttings, treatments. Marius takes me on a tour of the Garden: he makes a short introduction, pointing to the old greenhouse with two domes, the herbarium, the production greenhouse, the plant nursery – where they make tree seedlings. As we start visiting the Garden, we come across engineers and biologists in charge of various sectors.

Most of them seem a bit hesitant in making any strong statements, but they all say half-heartedly that the Garden lacks the money and that some visitors behave strangely. “One visitor broke flowers and said ‘I bought the ticket so I won’t leave empty-handed’,” recalls one woman. “We are very few and we are still at scissors-level, but we do our best,” somebody else says.

We reach the old greenhouse, is a historical monument. It was built between 1889 and 1891 after the design of the Liege greenhouses in Belgium. Part of it was revamped in 2011, thanks to a sponsorship. The Tropical Forest pavilion can also be visited now. However, the other pavilion and the central part still need to be revamped, and the Garden needs some EUR 300,000 to do it. Only employees are allowed inside, but even for them it can be dangerous, as big chunks of plaster have fallen off the building. It’s strange to witness the decaying beauty of this old greenhouse, which hasn’t changed much in over a century. But without work, its beauty is in great danger.

Mirela, a tiny, friendly engineer is in charge of the old greenhouse. She and two landscapers take care of everything from coordinating to cutting and attending the plants.

The old greenhouse closed to the public in 1976, when the new one was built. Most of the plants were moved there, except for the tallest, which have very deep roots and can’t be transplanted.

Some money did come. The Botanical Garden has received funding from the Swiss state: EUR 1.7 million to revamp the new exhibition greenhouse, which has eight pavilions. Seven of them were refurbished, but the pavilion which hosts the palm trees needs extra money. Too tall for the current building’s height, the palm branches have broken the pavilion roof several times. The Garden needs about EUR 1 million more to work on this pavilion.

The roses’ strength

While we move from sector to sector, I ask Marius, the rose expert, how come roses are considered almost universally the symbol of romance. They are the strongest plants in the garden and are in bloom from May to December, he explains.

However, the roses’ first bloom, which is the most important of the year, is lost if you have weather shocks, such as we are witnessing nowadays, Marius goes on. The roses’ first bloom at the end of May last year was the most spectacular in at least seven years. “It was an explosion.”

Much like roses, botanical gardens are symbols of romanticism in the middle of cities. They are strong and can survive winters, the passing of time and even bombing. But faced with dire financial straits, they might just fade.

The alternatives

In the last years, Bucharest’s Botanical Garden has hosted several events. In 2013 and 2014, it hosted “The Long Night of the Short Films”, a short film event. In April this year, a Romanian designer organized her shoe exhibition in one of the new greenhouse’s pavilions. For one afternoon, the Garden was flooded with trendy women and men, admiring the high-heel shoes scattered around plants and drinking a glass of wine. Romanian singer Dya filmed a music video in one of the greenhouses.

They helped create some awareness and brought more visitors. They add to the revenues from entrance tickets, but they also make it more difficult for the Botanical Garden to keep its educational role and not be mistaken for a friendly, cozy park in the Cotroceni area.

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com

(photos by Diana Mesesan)