Romanian film review – Nasty & European Film Festival

The documentary Nasty is still touring cinemas across the country (and streaming on HBO) so if you are into tennis, or just fantastic spectacle, do not miss it. Similarly, if you are in Brașov or Chișinău in the following days, check out the European Film Festival.

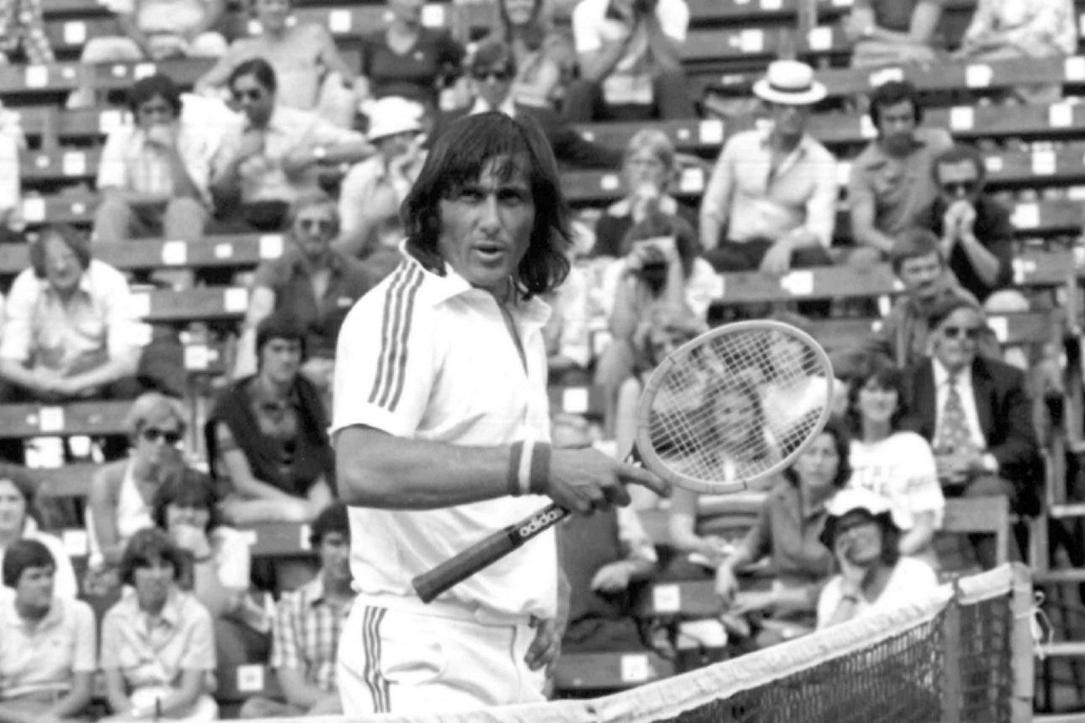

Nasty is Ilie Năstase, the legendary, original ‘bad boy’ of tennis. Tudor Giurgiu, Tudor D. Popescu and Cristian Pascariu’s doc looks at the heyday of Năstase’s career in the 1970s, using an impressive amount of archive material, mostly of matches and interviews. An impressive, creative athlete, he won countless tournaments and rose to no. 1 in the ATP rankings in 1973. A good pun and really fitting, Nasty was apparently his nickname, and if you think it might be mean, his antics on the court will prove it was apt. He teases, provokes, shoves, screams, jumps, throws his racket, swears, all very dramatic stuff. Mostly tongue-in-cheek, but not always. But drama also sells, and the full stadiums at the time show it. The media attention too: he was hugely popular. By the way, his other nickname was "Bucharest buffoon" (interestingly, I don’t remember the film including this info). But temperament and stunts, however hilarious in their child-like mischief, never outshone Năstase's game, which was truly revolutionary. What they did do was undermined his success; trouble was always in the way. What is certain is that he played out of fun and love for the game, and it showed, often in his nothing-to-lose attitude.

It is this joy and puckish troublemaking that carry the film, otherwise told pretty conventionally, alternating between archive footage of tournaments and media features, and many talking heads remembering Năstase, including tennis superstars Billie Jean King or Rafael Nadal. They pay homage to his influential game, but also his friendship and generosity. What is most moving about the film is the camaraderie between all players who had no trainers or agents, and so travelled, trained, and spent time together on tournaments. Those were other times, they say nostalgically, before tennis got more professional and (apparently) less fun and friendly.

However, other times also meant disruption, poor losing, and abuse spat out on the court was sort of accepted, or only mildly admonished. The more recent years brought more consequences for Năstase, who made headlines (and a complete fool of himself) with a racist comment about Serena Williams’s baby, only to go on and bully female players and trainers at another tournament. He shrugged it all off with his usual I-don’t-care-this-is-me attitude. Which is, at least according to what everyone keeps saying, repeating it over and over for the ones in the back, classic Năstase: temper and attitude were part of his charm, a façade, he did not mean it and he was (is) otherwise the most supportive, generous friend. Which may be, and invoking different times is valid, but the film is not willing to get to know the person Năstase better or present him on his own terms and in his own words. The young Năstase proves (surprisingly) introspective and eloquent in archive interviews, also in English and French, but the Năstase of today hardly says a thing, and when he does it is mostly a joke, or as a reaction. I wondered all through the film why. In the past years, his public persona has been tied to scandal, marriage-related gossip etc., all tabloid stuff, so I did wonder whether a longer conversation with the man of today would have completely hijacked the film. As it stands, it is a pure homage to the star of the 1970s, moving and entertaining, but just that, an homage with not much shade. He is a canvas onto which players, journalists, friends, adversaries (only on the field, as it seems) project their thoughts of love and admiration. Whenever there is a chance to dig deeper, or dare to show more facets, the films holds back. That also goes for the remarkable fact that he took tournaments by storm from behind the Iron Curtain, and what it meant for him, both personally and professionally. What was the reality of someone who travelled so often to the West, what did it mean, not only logistically? Glimpses of the political and social context are given, and they are terrific, but again, not given as much space as Năstase’s pranks. Even technical details about his game are only mentioned briefly; a strange choice. The show prevails.

These flaws do not diminish the film’s attraction, though. Nasty is by far Giurgiu’s most entertaining pic to date. Helped enormously by the fantastic match footage and Năstase’s over-the-top behaviour, this is fast, fun popcorn cinema, a true show. The man and athlete Năstase, and the man he has become, are the stuff for another film.

Every May brings an edition of Festivalul Filmului European. Organised by the Romanian Cultural Institute and backed by EUNIC, the European Union National Institutes for Culture, the fest showcases European productions of the current year. The 2024 edition, its 28th, boasts even more cities toured after the initial (and main) programme in Bucharest. Botoșani, Târgu Mureș, Sibiu, Chitila, Curtea de Argeș have ended, leaving the last two stations, Brașov and Chișinău, to kick of on 24 May and 6 June, respectively. Nicolas Philibert’s topical documentary On the Adamant/ Sur L’Adamant is the standout among these two local selections. The Adamant of the title is a floating structure on the river Seine in Paris, hosting a daycare facility for persons with psychiatric conditions.

The other standout in this year’s overall selection is another documentary, coincidentally also French, Guillaume Cailleau and Ben Russell’s Direct Action, an unhurried observation of a large activist community in the north-west of France. Direct Action is hypnotic and more than topical (a word I overuse here, but only because it is the most fitting). It does not try to convince you in any way but what it does is show how being an activist might indeed be the only way, given the current political and environmental context. An astonishing film. Switching to fiction, Stephan Komandarev’s Blaga’s Lessons is just as attuned to the present and its challenges (read: traps), a tense, intriguing thriller about a Bulgarian pensioner who takes increasingly shady roads after she is scammed out of her money, while Levan Akin’s Crossing, no less relevant, manages to make a trans story into a fantastically warm crowd-pleaser, arguably the festival’s most uplifting film.

By Ioana Moldovan, columnist, ioana.moldovan@romania-insider.com

(Photo info & source: still from Nasty // Transilvania Film/ Libra Film Productions)