Could Romanian football come home? The consequences of short-term thinking and the gaps to close

Nearly 100 years ago, in 1930, totalitarianism was thriving in more and more parts of the globe, the world had less than half of the number of nations today, and football was played with a leather ball and a 3-2-5 or 2-3-5 formation. The first number was, obviously, the defenders. Seeing how different football is compared to back then, one should bear the big picture in mind. To even consider a talk about Romanian football, one should distinguish between significant time periods and their country’s national team and clubs’ achievements.

The National Team

Back to 1930: Romania accepted to go to Uruguay for the first-ever FIFA World Cup, something other European countries refused because of the difficulty of travelling. They won with Peru and lost against the host country and tournament winners. Given the political contexts of the interwar period, many nations did not participate in the first World Cups.

Nevertheless, Romania was there for the first three, losing their first and only games in the tournament, in 1934, against Czechoslovakia, and in 1938, against Cuba. The next time they would qualify for the final tournament would be in 1970.

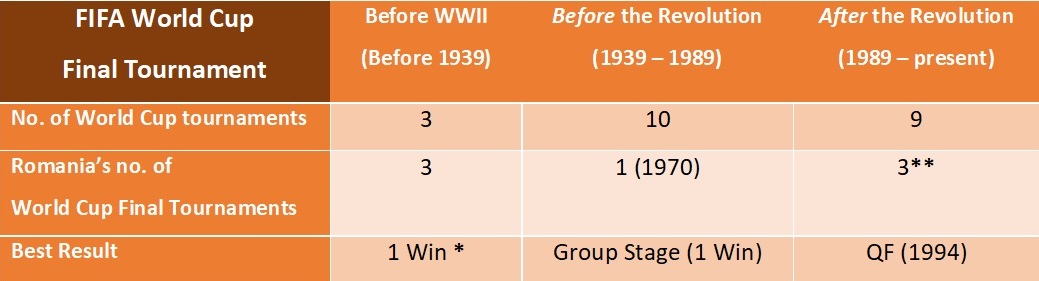

The global context has influenced football, and Romania has served its moments of glory, together with those of absolute silence. Based on last century’s significant world changes, Romanian achievements in the FIFA World Cup could paint the following table:

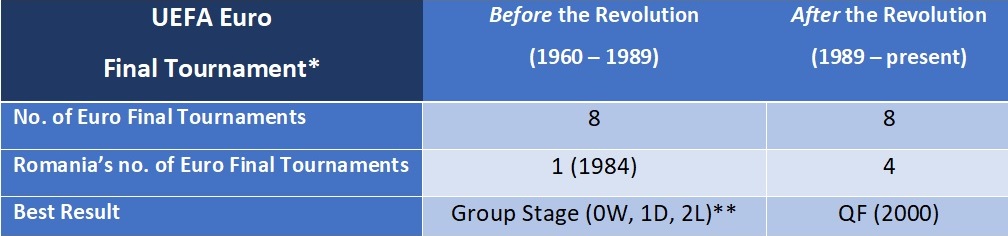

Narrowing down to the continental theatre, European countries’ names and borders changed several times in the 20th century, reaching a somewhat similar shape to what is seen today only at the beginning of the 1990s, with the fall of the USSR and the breakup of Yugoslavia. This period coincided with the Romanian Revolution. Therefore, one could consider that Europe, as it is known today, has, with few exceptions, existed since 1992. UEFA’s European Championship has existed since 1960, so the period until today can be split almost equally by the early 1990s events. Therefore, one could draw this table:

Considering the countries with similar political backgrounds and geographical proximity, Romania’s Quarterfinals (QF) in the 1994 World Cup were rather decent for the post-1990s era. Hungary’s best results in the World Cup are two finals, in 1938 and 1954, and Poland won third place in 1974 and 1982. Given the similar backgrounds and development efforts, Serbia and Ukraine could be considered as well in this comparison. Serbia was part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, together with Montenegro, until 2006. Seeing Serbia’s results since the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1992, and Ukraine’s results since the fall of the USSR in 1991, the former did not proceed from the Group Stage, while Ukraine reached the quarter-finals in the 2006 World Cup and 2020 Euros. Nevertheless, Bulgaria’s fourth place in the USA in 1994 could be considered the best result in the region after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

It can be easily spotted from the numbers above that the Romanian national team has never excelled in global and continental performances, reaching absolute glory in the 1990s. Regardless of the top performances, it cannot be ignored that the Romanian national team qualified for more Final Tournaments after the 1989 Revolution (7/17) than before it (5/21).

The rankings

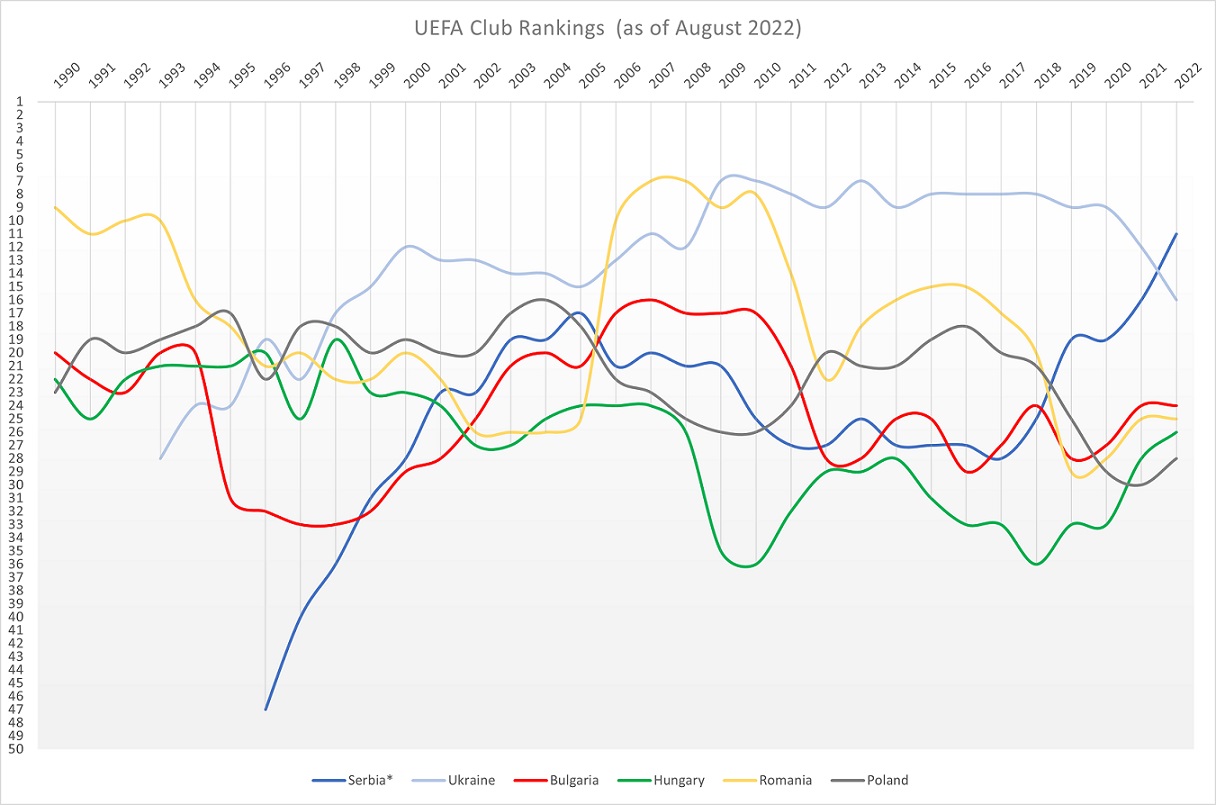

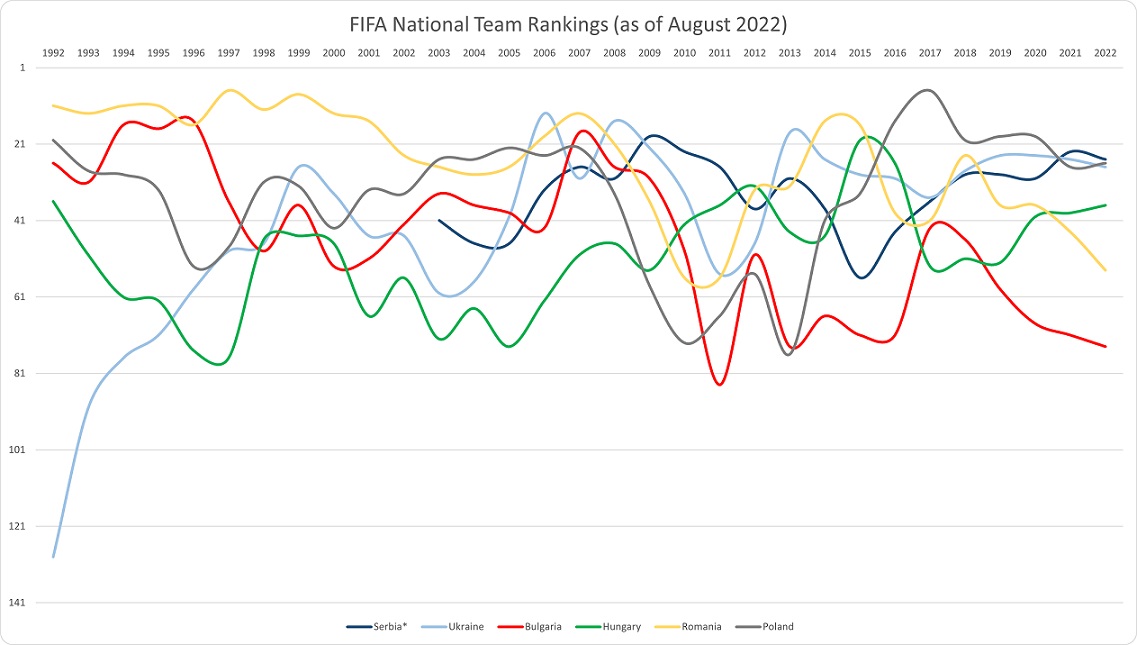

Another way of looking at the big picture is the FIFA and UEFA rankings. Whilst the FIFA rankings for national teams were only created in 1992, UEFA club coefficients have existed since 1956. Since national teams and football clubs are two different types of entities, one should consider each of them separately.

Sticking to the post-1990s era, the best Romanian club result was the 2005/2006 Steaua Bucharest’s UEFA Cup Semi-Final against Middlesborough. Occasionally clubs such as CFR Cluj, Rapid Bucharest, Dinamo Bucharest, Astra Giurgiu or Unirea Urziceni exited the Group Stages of the European competitions. Furthermore, none, but Steaua and Rapid in 2006, made it to the quarter-finals or above.

One of the most important conclusions, looking at the two graphs above, is that the Romanian national team and club performances rarely correlate. There are several reasons for that, such as foreign players joining club teams, or the different types of investments each of them attracts, individually. However, the striking commonality in the two graphs is that, since 2012, Romania has had a short rise, followed by a sudden fall towards all-time lows in both.

The theory of change

There are reasons to analyse what happened around 2012 and how such events targeted short-term returns on investments. Due to bad management, for ten years and ongoing, several club owners have been sent to jail, and countless teams have gone bankrupt. As of the 2022/2023 season, there is only one team, out of 16, in the Romanian first league that was founded before 1990 and has never been dissolved: CFR Cluj.

More interestingly, in 2012 and 2013, Răzvan Burleanu and Gino Iorgulescu became heads of the Romanian Football Federation and the Romanian Football League. These two entities manage the national teams and the first league, respectively.

Regardless of speculations, coincidences, and pointing fingers, one would agree that Romanian football needs a change. Bogdan Codorean, a former player for CFR and Universitatea Cluj, retired from football because of an ACL injury. Another reason was mathematics, which was a better prospect than Romanian football. He says that “regardless of how much we build and develop in Romania, currently, other countries progress quicker. So, fundamentally, we regress.” Then, what should change for the better?

The predominant public conversation in recent years was that the mentality and attitude of Romanian professional footballers lack a series of qualities that could determine performance. Thus, one possibility to improve Romanian football could be to improve the psychology of the individual footballer.

Giani Boldeanu is a sports mental coach and agent, and now works in the UK with young talent from around the world to maximise their potential. He started learning psychology from his brother’s books when he was 13: “I probably did it so I could develop a defence mechanism. Growing up in a rough neighbourhood, you had to learn tactics, but I applied them later in the army as well. During the first few weeks, we were 40 guys in three bunk beds. While others were weeping, I was aware I was doomed, so I tried my best to keep calm,” Giani remembers, laughing.

However, the view on psychology in football is still surrounded by stigma and scepticism, even in British football, where only one in four academies have a psychologist. “Footballers have extremely high self-esteem, mainly because all the eyes are on them. So, they refuse to talk openly about their problems because they feel some sort of shame. If they haven’t scored for two years, they would rather go home and cry, than talk about it with a specialist,” Giani says.

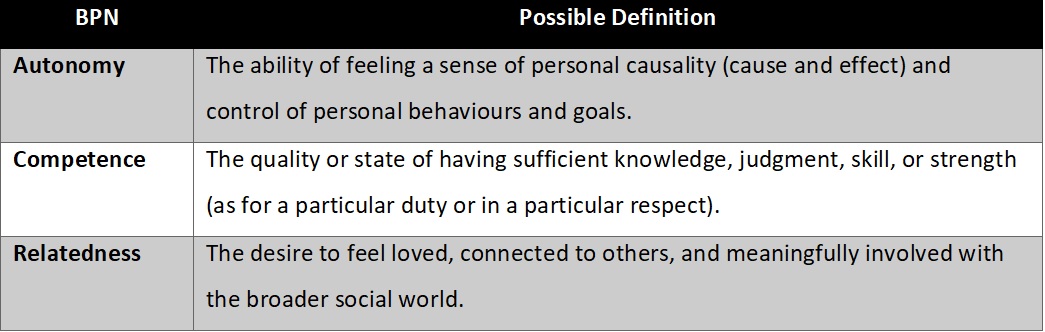

Studies by Deci E., and Ryan (2008) and Nicholls (1984) proposed some of the most comprehensive theories on self-determination (SDT) and achievement goal (AGT). According to them, one could summarise that personal motivation to grow and change is determined by three basic psychological needs (BPNs):

Autonomy

According to Giani, Romanian footballers’ goals and behaviors are influenced by everything that happens around them, and awareness plays a key role: “It often happens for footballers to end up in the wrong groups or to be surrounded by the wrong people. So, when I start working with a player, I ask them about what they eat, what they read, how much they sleep, what they do in their spare time or how they train. We talk about these things because mental coaches need to ask them questions if nobody else does,” Giani says.

It seems like autonomy is linked directly to the quality and expertise of those teaching footballers about football. Giani adds that those people have such an important role that “when a Romanian player finds something difficult, usually they stop doing it, or they are waiting for a suggestion from the coach. The reason for this is because everything is results-driven since junior teams, the coaches have no choice but to fight for results, and it’s the quality of the player and of the football who get stuck,” Giani explains.

This idea is reinforced by Bogdan, who thinks that many Romanian players have just an illusion that they have potential, and those who have it do not have the right people around them. “Knowing “Adiță” (Adrian Păun, CFR Cluj), I know very well that he has plenty of talent and skill. He is a great footballer! But if he had better people around him to give him the right feedback, to tell him of a better way to eat from an early age, maybe he would’ve been now in the Top 5 leagues,” says Bogdan. He suggests Romanian footballers research training and tasks and try them by themselves as a form of compensation for the lack of external support. “It is not rocket science what they do in other academies in Europe. They didn’t reinvent the wheel. We could do it too if we had the necessary infrastructure,” he adds.

Competence

Competence is, arguably, the least satisfied BPN in Romanian football and the one that is influenced the most by infrastructure. Even though there are more modern stadiums now, the academies and technologies used in Romanian football are, for the most part, below par.

Bogdan remembers how he was struggling because of the poor conditions. “Infrastructure is an umbrella term that encompasses coaches, nutritional guidelines, good pitches and more. Cluj, Bucharest and Constanța might be the only places in the country where players can develop accordingly. Regardless, when I was in the circuit, there was no U-21 coach able to tell me how to reach mastery in certain skills, and I don’t know if there are any today,” Bogdan recalls.

While there are many external factors connected to competence that footballers cannot control, awareness and continuous learning could be the key. “The trick I always tell them to learn is to know, at every single moment of a game, the following: where the ball is, where they are, where the opponent is, and what the next step is,” Giani says. He mentions how some footballers, in the rare instances when they ask for help, they do not ask the right people: “Some Romanian players still call on prayers, instead of going to specialists. They come in for sessions with me, saying at the beginning that 10-20-40% of skill is in the mind but leave the meeting realising the real percentage is closer to 90,” Giani says.

Relatedness

According to a Spanish study on U18 players, relatedness is key in promoting reflective thinking and lowering concentration disruption. Or simply put, if one feels loved, valued, and connected with significant others, that can improve their focus and awareness of their own knowledge.

Narrowing down relatedness to the quality of relationships, Romanians have, by default, a significant handicap. Daniel David, arguably the highest profile Romanian clinical psychologist, mentions some relevant key features of the average Romanian in the volume The psychology of the Romanian people:

(approximate English translation)

According to Bogdan and his experience, there are three important types of relationships for a footballer: “Parents and close friends who define your character, the coaches who help with technique and tactics, and an agent, someone who understands in what type of organization the player would fit better,” says Bogdan.

“Parents are crucial for a young footballer because what they do on the pitch is connected to the relationship with their family. Also, when they enter the academy or the club, they should respect everyone around them, from the coach and cook to the cleaner and the doorkeeper. Why? Because the players meet them every day. It’s like their other family,” Giani says. He also thinks that, in the absence of their family, players from academies can benefit from a mental coach. “It is exactly the same process as a church confession, but there might be higher chances I could fix their problems,” Giani states.

As expected, on the journey to better performances, Romanian footballers encounter problems they can control, and some they cannot. Football fans cannot expect top performances from their favourite football teams without a framework that fits the day and age we are currently living. There are hopes for further development in academies and infrastructure, with the most recent example of Rapid’s co-owner investing EUR 10 million in youth development.

New management laws and procedures are needed, some that could help both the quality of the competition, but also the relationships between the parties involved. In recent years, there have been a series of moments that proved the incompetence of the system or the people involved. Some significant occasions could be the slow death of Gaz Metan Mediaș and Academica Clinceni, the Cortacero story, or when the third league’s competitors were announced eight days before the start of the season. The main problem in management is probably the lack of long-term strategies, leading to reduced certainty and predictability. This, combined with the still existing dependability on volatile public funding, leads to the situation where the federations act after the worst has already happened.

Regardless of the uncontrollable, football players have, from an early age, a lot of work to do if they want to be among those 0.012% who follow a career. However scary that number is, and even though it might be higher in Romania, young footballers have, as Giani has previously mentioned, more control than they think. “As a young player, your expectations are highly influenced by others, unfortunately. That is why many talented painters become footballers, and many talented footballers become painters. However, with an open mind and continuous learning, you get closer to your goals. For example, do you think Cristiano Ronaldo said ‘no’ to learning?” Giani asks, rhetorically.

As a former footballer, Bogdan Codorean explains what kind of hints make a football player more aware of where they are in their career: “Firstly, you can see how good you are based on your professional contract. Then, see if you have mastered the specific skills for your position, and think if you are a good person with a decent character. Finally, if you want to become a footballer, you should like doing it because it is your choice,” Bogdan says.

A decent character can be easily spotted on the pitch. For example, if one watches a Romanian Superliga game, they will quickly notice a few obvious differences in the players’ personalities compared to a Premier League match: the dives are more theatrical, there are more frustrating fouls to stop counterattacks, and the arguments with the referees are more common. Some people say it is the lack of experience, but experience comes from results and, more importantly, from international results. And these results come if players adapt to the demands of modern football.

It is hard to say if the quality of the football would improve if the players dived less, but one thing is sure: fans would enjoy it more. That might bring them to the stadiums, which, in turn, would equate to more funds or even a more attractive deal for investors.

by Ștefan Paiu, features writer

(Opening photo: Cosmin Iftode | Dreamstime.com)