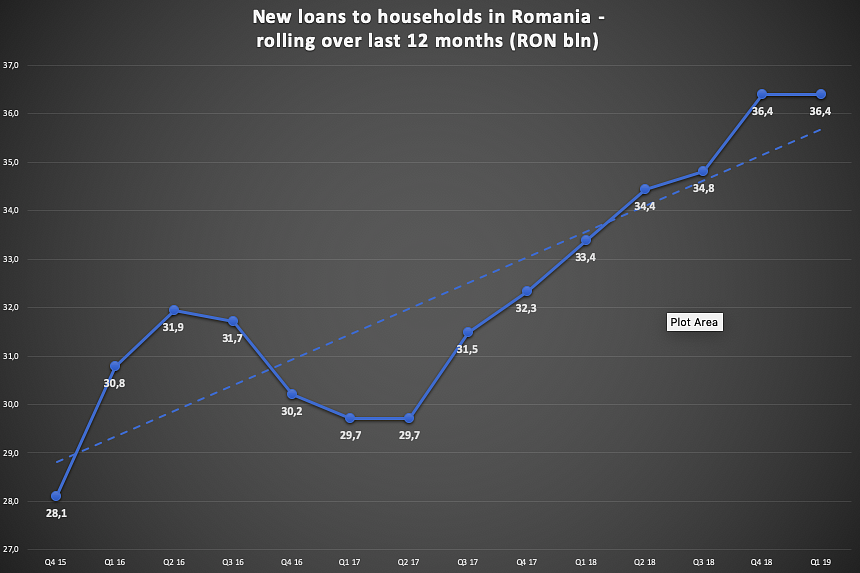

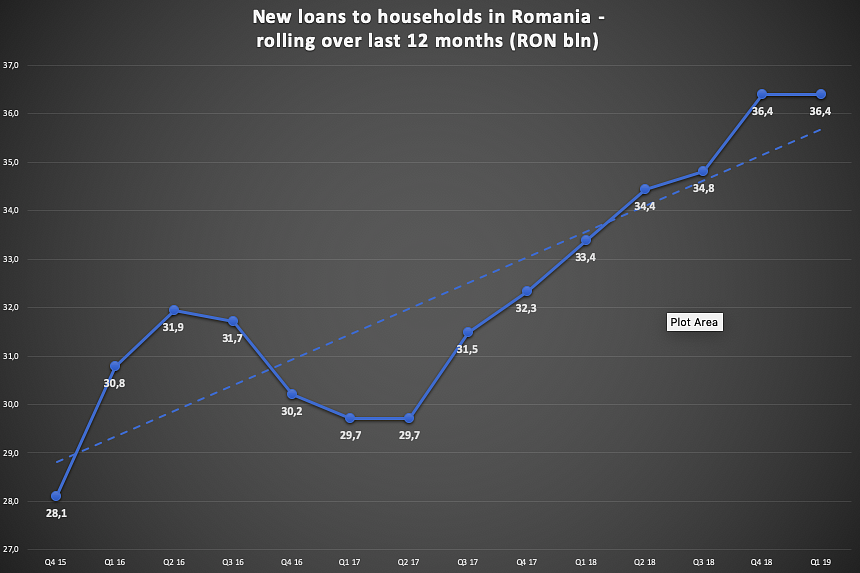

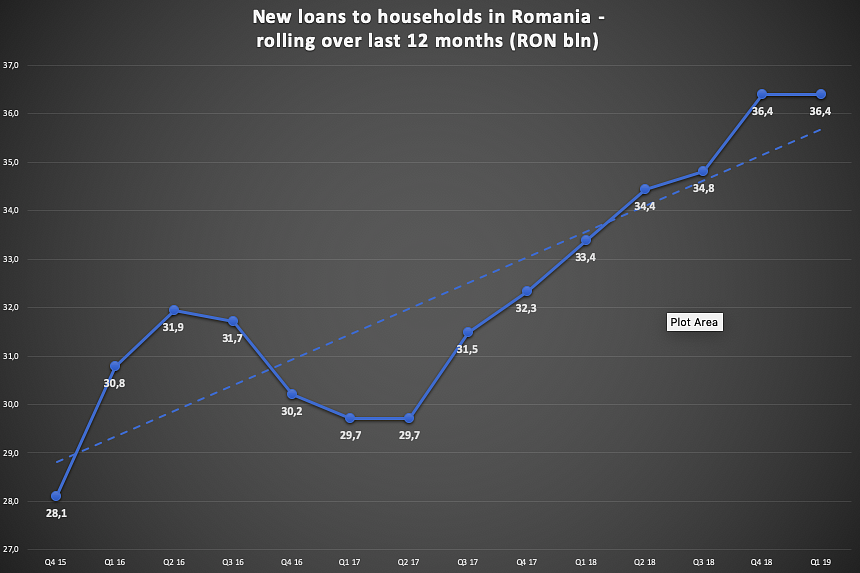

Chart of the week: Romania’s lending to households at a standstill in Q1

The volume of new loans extended by Romanian banks to households remained at the same level in January-March this year compared to the same period last year: RON 7.6 billion, or EUR 1.6 billion. The stock of loans advanced by 1.4% year-to-date (or by 8.1% year-on-year) at the end of March, but this was still insufficient for offsetting the 2.1% headline inflation. The stock of loans thus contracted in real terms through the quarter.

The standstill came after a hectic credit market toward the end of last year, possibly as an effect of the emergency ordinance (OUG) 114/2018 that created panic among banks and high (partly false) expectations among debtors. The volume of new loans extended in the last quarter of 2018 advanced by a robust 20.8% year-on-year rate while the average growth rate was 12.6% in 2018.

Several factors, such as rising interest rates and simply the saturation (households reaching indebtedness limit), contributed to households recently taking a slightly more cautious position. Given the change in regulations (benchmark interest rate being changed, higher interest rates expected and rising economic uncertainty prevailing), new lending patterns are expected from now on. But the dynamic residential real estate market and households’ appetite for consumption support further credit expansion -- particularly as the indebtedness ratios have eased following GDP and wage increase recently.

Consumer and mortgage lending follow different patterns

The consumer and mortgage loans are rather different in nature: as products consumed by households, but also as businesses for the banks. Consequently, they do follow very different patterns, and their dynamics over the past years have proved it: mortgage lending reached a standstill as early as second quarter last year (when the volume of new loans extended were only 5.1% up on an annual basis), while consumer lending maintained high growth pace until the last quarter last year (+35% year-on-year). In Q1 this year, new consumer loans were RON 4.76 billion (EUR 1 billion, up 2.2% year-on-year) while new mortgage loans were RON 2.75 billion (EUR 0.6 billion, down 2.5% year-on-year).

Consumer lending differs from mortgage lending also in regard to the dynamics of the stock of loans: while the stock of consumer loans in banks’ portfolio has remained roughly constant over the past two quarters (close to RON 58 billion, or EUR 12.2 billion, at the end of March), the stock of mortgage loans keeps rising at steady pace (to RON 75 billion, or EUR 15.8 billion). Given the longer maturity of the mortgage loans, the stock of mortgage loans is less sensitive to the change in the volume of new loans from one quarter to another. In contrast, the stock of consumer loans is more volatile depending on banks’ generation of new loans.

Households’ indebtedness ratios eased over past years…

Despite the active lending activity over the past years, households’ indebtedness ratios have actually stabilized or eased (depending on the metrics used) thanks to the even stronger rise in their incomes and to the advance of the nominal GDP. Thus, the stock of loans contracted by Romanian households at the end of 2018 accounted for 14.1% of the year’s GDP and 83% of their net aggregated wages. The ratios were significantly lower than four years earlier (15.1% and 107% respectively). Particularly the loan-to-wage ratio has decreased, as the wages have increased sharply. It means that households owe to banks roughly 83% of their annual net wages now, compared to more (107%) than their annual net wages. From the banks’ perspective, this means more room to lend, but this also depends on the distribution of wages: high-income households tend to contract mortgage loans while low-income ones rely on consumer loans.

When it comes to the intensity of borrowing/lending (net loans compared to either GDP or households’ total net wages), it has stabilized when measured as new loans to GDP. Thus, the volume of new loans extended by banks to households in 2018 accounted to 3.9% of year’s GDP -- not far from the ratios seen in 2015-2017 but one percent more compared to the ratios seen in 2011-2014. Both figures are, however, well below the 8.5% of GDP worth of loans poured by banks in households’ accounts in 2007 (the ratio slightly eased to 6.9% in 2018).

The volume of new loans extended by banks to households accounted for 22.8% of households’ net aggregated wages, in 2018. In other words, households borrowed in the amount of 22.8% of their annual wages (consumer and mortgage altogether). The ratio decreased from 27.9% in 2015. In 2008, it was as high as 50%.

…but they are not particularly low by EU standards

The debt held by eurozone households fell in the third quarter of 2018 to 57.6% of the area’s GDP, the lowest level since 2006, according to a global debt monitor database produced by the Institute of International Finance and quoted by Financial Times. Households debt to GDP in the euro area averaged 57.1% from 1999 until 2018, reaching an all-time high of 64.1% in the fourth quarter of 2009 and a record low of 46.3% in the first quarter of 1999. The 2018 indebtedness ratio for the eurozone is lower than that for the US, where household debt is 75% of GDP, and significantly below the 86% in the UK. Scandinavian countries tend to feature high indebtedness ratios, paralleled with record real estate prices. Romania’s 14.1% ratio at the end of 2018 is particularly low compared to the eurozone area.

Nonetheless, the low GDP per capita in Romania (65% of European Union’s average in 2018, in comparable prices) means that Romanian households spend a larger share of their incomes on food and utilities being left with a smaller share of their revenues for discretionary spending. It signifies that for the same indebtedness ratio (debt to GDP, or debt to net wages), Romanians face tighter financial constraints servicing it. This is particularly valid for low-income families likely to contract consumer loans, where the housing and food expenditures account for a very large part of their incomes. But the wide differential between the indebtedness of Romanian households (measured as a percentage of GDP) and that of households in the eurozone suggest potential for further lending in the country. This is, however, just an overall picture -- with details such as the distribution of incomes among households, the price of real estate assets, the distribution of credit between consumer and mortgage loans pointing to different conclusions for each product or segment of the population.

By Iulian Ernst, Editor Romania-Insider.com; iulian.ernst@romania-insider.com