The Romanian teenager who documented the ‘80s in Communist Romania

Andrei Birsan meticulously took pictures of his friends throughout the ‘80s, one of the toughest decades for Romania. Some 30 years later, these photos are the collective portrait of a generation.

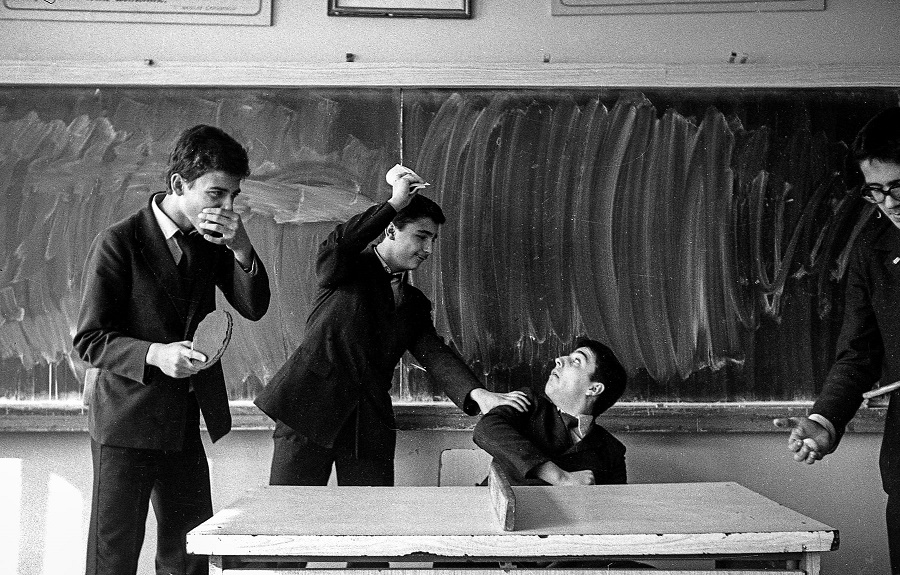

Two high school students are playing ping pong on the teacher’s table. Another one sits on the teacher’s chair and looks up to one of his colleagues who wants to crash a paper airplane onto his face. They are all laughing and wearing school uniforms, including ties. It’s the early ‘80s in Communist Romania.

The students are totally unaware of the boy who is behind his tiny Russian camera and takes a photo of them. The photographer is called Andrei Birsan. Without knowing, he is documenting the story of an entire generation. At 16, though, the pictures are just for fun. He loves his colleagues and the experiences they share. Photos are a means to hold those moments a little longer.

The negatives remain in boxes for decades. When Andrei turns 50, he decides to organize an exhibition with all the photos he took the ‘80s. It’s his own birthday present.

“Some powerful images from a pretty powerful time”

Bored Panda picked up on his pictures and published a story titled “My Life As A Child, Teen And Student In The Communist Romania.” Black and white photos showing teenagers in Communist Romania, who were having fun and creating a sort of personal freedom in times of restriction.

I met Andrei on a rainy Sunday morning in Bucharest. Now 51, the man wears a large jacket and a checkered shirt. He holds in his hands a tiny, discreet Fuji camera.

I met Andrei on a rainy Sunday morning in Bucharest. Now 51, the man wears a large jacket and a checkered shirt. He holds in his hands a tiny, discreet Fuji camera.

Andrei has kept 280 film negatives of the photos he took in the ‘80s; that’s more than 8,000 photos. He started scanning them in 2006. “It’s not so much actually,” Andrei says. “I was not very constant in taking pictures.”

He was in the 8th grade when his mother gave him a Smena camera as a Christmas present. The 14-year old boy started taking pictures of his colleagues in elementary school. He would soon become invisible to all his colleagues. He would take pictures during classes, and teachers and students alike would ignore him. Even as a very young photographer, he was very discreet and could easily blend in.

“It was a family album with my friends,” Andrei says about his old photos. “We were doing a lot of things together. Maybe because there was no Internet, no Facebook, we were hanging out together all the time, kite flying, going on trips.”

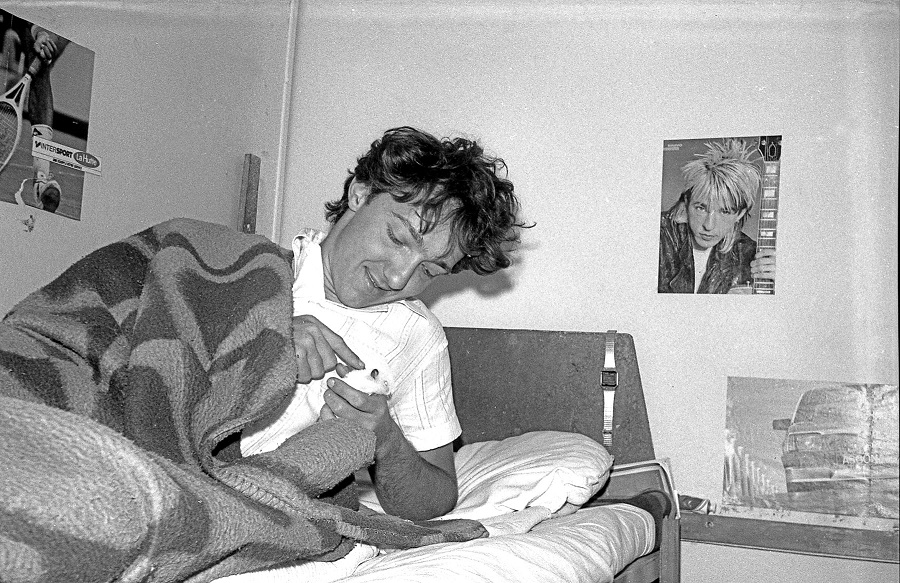

As kids, they weren’t really aware of the limitations of those times. The image of Romania in the ‘80s is synonymous with food shortages, long queues for the most basic products, censorship, winters without heating. The pictures of Andrei show a different story. Kids are laughing like crazy, teenagers are drinking, smoking.

That joyful experience of childhood and teenage years was possible only because parents were there to create a space where kids felt protected, Andrei explains.

That joyful experience of childhood and teenage years was possible only because parents were there to create a space where kids felt protected, Andrei explains.

Andrei’s book that gathers all these pictures has different levels. It’s the story of kids, the story story of parents, the story of Bucharest, and indirectly, the story of those enjoying privileges in the Communism.

Andrei became aware of the documentary side of his photos some years ago. Last year, when he turned 50, he decided to organize an exhibition in Bucharest with all the photos.

Reactions to the exhibition were amazing. It wasn’t only about Andrei Birsan and his friends. A whole generation could recognize itself in the pictures.

This year Andrei has put together all the photos in a book. He sent some copies of the book to his old colleagues, just like in high school, when he would print the photos and give them to his friends as gifts. It was really emotional for him, and for his old friends as well.

Alina, a friend who moved to the United States more than 30 years ago, wrote an email to Andrei in a combination of English and Romanian.

Alina, a friend who moved to the United States more than 30 years ago, wrote an email to Andrei in a combination of English and Romanian.

“I remember how much fun we had even when we were doing patriotic work. I love the image with the teacher with the shovel in her hand and her bag on her arm. The pictures captured candid moments, but in a very precise way. They chronicle honestly, but are cleverly poignant. I don’t know how to explain that in Romanian, but they are some powerful images from a pretty powerful time.”

The Vigilant Woman

Andrei Birsan didn’t feel that his photography was subversive, not even when he photographed the demolitions that were cleaning up large parts of Bucharest.

By 1984, the old Uranus neighbourhood had been demolished and the construction of the Palace of the Parliament began. It is now estimated that between 20,000 and 100,000 people worked on the site. That year Andrei went to the Izvor area to take some pictures of the construction process. He was 19 and was beginning to notice the world around him.

A “vigilant” woman pointed to Andrei who was photographing on the construction site. She screamed “Catch him!”. This caught the attention of a policeman who took Andrei to the man in charge of the construction site. The engineer proved nice. He told Andrei that it’s not allowed to take pictures there, so he’ll have to remove the film from the camera. He returned him the camera and told him: “Be cautious. A small thing can destroy your life.”

When the ‘89 Revolution started, Andrei was living in a small place with no TV. He was 24 then. On the morning of December 23 he took the subway and went to the city centre. He had his camera with him. There were shootings, but nobody knew who was being shot and who was the enemy. The students were then called to the University to defend it. Andrei, who was a student at Polytechnique, joined the other students. They were given guns and had to protect the empty classrooms. The students spent the Christmas there. A girl had brought a fir tree, Andrei recalls. He knew that things were irreversible.

“It was a huge unchaining,” the 51-year old man recalls with tears in his eyes.

“It was a huge unchaining,” the 51-year old man recalls with tears in his eyes.

Andrei takes a sip of his espresso in a cafeteria in Bucharest. On a plate there are some apricot-flavored cookies. In the transition years that followed, he has worked in the banking sector, had a daughter, and set up an association called “My dear Bucharest”.

“How do the ‘80s seem to you? Are they still close or do they seem part of a distant past?”

“Oh, they are very far away,” Andrei says with a warm, sad smile.

Then he adds: “The ‘80s are still a recent memory for us. People still have memories about those years. That’s why it was important to publish the book now. Had I waited for another five years, maybe those times would have remained too far away”

***

Andrei Birsan will launch his book “The ‘80s” on Wednesday 28, at 6.30 pm, at the Bucharest Municipal Museum. The book is printed by the Bucharest Municipal Museum and opens a series of books called: The Time of the City.

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com