Solutions needed for Romania’s all too frequent droughts

In his latest agriculture comment piece, guest writer Stuart Meikle tackles the topic of irrigation and the set of measures needed by Romania's agriculture, which has been facing droughts. The consequences of these, coupled with the lack of centralized measures could have an impact on all layers of society, especially on the household food supply of small agriculture workers in the countryside.

In his latest agriculture comment piece, guest writer Stuart Meikle tackles the topic of irrigation and the set of measures needed by Romania's agriculture, which has been facing droughts. The consequences of these, coupled with the lack of centralized measures could have an impact on all layers of society, especially on the household food supply of small agriculture workers in the countryside.

It was interesting to read within a critique of the first 100 days of the Ponta government that it had taken no action to prevent the impact of the current drought. To be fair, to expect your government to bring forth an intervention of a Biblical nature is a little much. But then analysis and rational is not what 2012 is about.

Romania, regardless of what one thinks of its communist political system at the time, invested massively in irrigation systems. They were, however, designed to supply water to state-controlled land areas and to levels that needed heavily subsidized energy. It was a state-organized operation that assumed long-term land control. In agriculture the ability to invest for the long term is imperative, especially with infrastructure investments like irrigation. Long-term land control is absolutely critical. Lose the control and the investments can/will be jeopardized.

Whatever the politics of post-1989, the culprit that caused the loss of Romania’s irrigation and drought-management systems was the land-privatization methodology. It gave no regard to the needs of agriculture and food production. Every government since has inherited the agricultural problems derived from the fragmented land structure created by privatization. The still-far-too-many, outstanding land-transfer and cadastral issues only makes matters worse.

Irrigation still operates, but one should ask, how much of this is on the still-state-owned farmlands along the Danube? If these had also been distributed and fragmented, would they be irrigated now? Their vast scale, their long-term rental-from-the-State tenures and their close-to-the-river locations certainly facilitate private-sector irrigation investment.

Here is the a conundrum for a right-wing, ‘leave-it-to-the-private-sector’ government. The irrigation systems were not built in a free-market era. They were designed for centrally-controlled management that does not fit with a laissez faire ideology. Hence, it is no surprise that little has happened in recent years. If the government is now going to further irrigation rehabilitation it will only be after it accepts that food security and free-market resource-allocation do not always go hand-in-hand. Laissez faire was a response that the British government used to the Irish ‘potato’ famine. It resulted in starvation and mass emigration. So far, Romania has only seen the latter.

So where does one go from here? As after the 2007 drought, the government will probably have to, at least, support the establishment of the crops for next harvest. Should it? If we follow a right-wing ideology, agribusinesses should be allowed to go bankrupt. Another drought in 2013 and they may well anyway, regardless of any intervention taken now. If one ignores food security, should the government intervene? In times of austerity does it even have the money?

Of course we will hear more about insurance. It is a ‘red herring’ as investment is needed in drought-management tools, not financial instruments. Paramount is preserving the crop whereas insurance is only about saving the business and coincidently protecting the State Budget after the crop is lost. I read recently about the Director General of SC TCE 3 Brazi saying that it is about soil management and moisture-conservation farming methods and looking at Iberian experiences. These sound like the kind of practical, common-sense, farmer-solutions needed.

The 2011/12 droughts have upped the call for large-scale irrigation rehabilitation. Should this happen? If yes, should it be done using public funds (EU or otherwise) if the beneficiaries are predominately large-scale, privately-owned agri-businesses? They will see improved profitability and capital gains on their land holdings. Is the food security argument strong enough to justify public expenditure? Maybe, but not if the production is going for export. It will also depend on how much benefit will trickle-down to smaller-scale farmers operating within water-management associations.

There is also a group of people who have gone unmentioned. Just how many smallholders have been impacted by the drought? For them it is not about income, it is more about their household food supply. Many are also aged with little opportunity to leave to find alternative income sources to survive. This group of society is large and it includes pensioners and those deemed as ‘self-employed’ in agriculture. The smallholding is a major part of the pension and social-support system in Romania and it is a safety-net that has enabled many of the poor to survive. With this safety-net failing in this time of austerity, one fears for the future of many rural dwellers.

It is imperative that the food supply for drought-impacted smallholders is fully assessed. Given that ‘austerity’ has not been accompanied by real reforms (it is easier to blame the international crisis), there is no imminent economic revival. Hence, where are the funds to help those rural folks long deserted by their government and now deserted by He-who-provides-the-rain? The social crisis in rural Romania has largely gone ignored and now it might just die out, literally.

To return to drought management. As I have said in other articles recently, the food-security supply-issue should be resolved by focusing crop growing in higher rainfall areas. Where higher-value crops like potatoes can be grown, this may be supported by on-farm irrigation investment. Irrigation investment to supplement normally higher rainfall away from the flatlands never gets a mention but it may make actually more sense.

Is climate change exacerbating the situation in the south? In the uplands, temperature rises may be linked to recent deforestation but down south that occurred a century-and-a-half ago. If one accepts the climate-change argument, the solutions need to be wider than irrigation-system rehabilitation. High temperatures, low rainfall and wind is a nasty combination. Soil erosion is a growing issue. Direct water losses and high plant transpiration (yes, plants ‘sweat’) rates are expensive problems to solve. Just pumping more water is not the solution, it is just too simple an approach.

Saving Romania’s ‘grain basket’ needs a long-term vision. It is going to take years of investment and a government approach focused on intervention. It is going to require solutions for larger-scale agriculture and the subsistence small-holder. It is going to be about using various techniques to combat climate-change. It is going to be about turning back the clock with reforestation. And within this irrigation is going to play a part, but it is only one piece of the jigsaw.

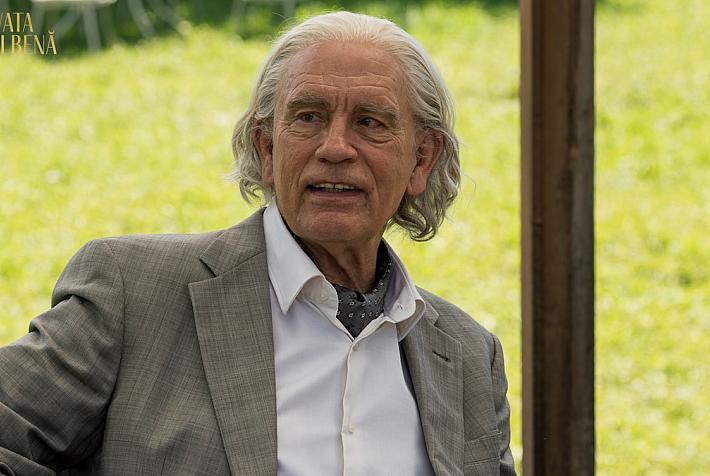

By Stuart Meikle, Guest Writer

Stuart Meikle is an agricultural management consultant. He was a University of London academic and is an economist, a writer and a farmer. He has been involved within Romanian agriculture as an adviser, as an executive manager and as an observer for 15 years. The views expressed are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Romania -Insider.com