Stories from the oldest pharmacy in central Romania’s Cluj Napoca

It’s a sunny, biting-cold, autumn Saturday morning. Cluj-Napoca is hyper as always, swarming with students. The taxi driver, a friendly Hungarian man, has no clue where the Pharmacy Museum is.

“It happens to me all the time,” says Ana Maria Gruia (pictured above), who works as a guide at that museum. “So I tell taxi drivers that it’s near hotel Melody.”

The museum is, indeed, hidden; but it’s hidden in very center of the city. Right across the street, there is the Lutheran Church. Melody, a famous hotel built in the 19th century, is 50 meters away.

The museum building hosted for centuries a real pharmacy. It’s often described as the first pharmacy of Cluj-Napoca.

In front of the entrance door, you can notice a small banner announcing the Harry Potter exhibition, which ended some time ago.

Another big banner, showing to the Ferdinand Boulevard, warns people that the museum is in great danger. It can be evicted any time.

The story of the small pharmacy museum located in the center of Cluj-Napoca starts in the 16th century with a rebel Saxon of Transylvania. Ousted from Hermannstadt (the current city of Sibiu) and Kronstadt (now Brasov), the pharmacist moved to the north, in Cluj-Napoca, where he set up the first pharmacy in the city.

The little medieval pharmacy was a big thing for centuries. People would go to the pharmacy to buy drugs, candles, cosmetics, balms, but also for exotic, more expensive products. Was your young wife lacking interest in sex? No problem, just a little lizard dust from the Orient, and things would get more intense. What about feeling tired all the time? There was the real mummy dust, the best of the best. No only did it energize you, but it also drained your pocket.

Then, just like under the curse of some noble man from Cluj-Napoca, unhappy that the lizard dust didn’t work, things rushed towards destruction.

In 1949, the pharmacy was nationalized and turned into a bakery. It was similar to the fate of many businesses in the new Communist Romania. The Baroque paintings of the entrance room called Oficina, remained. The other objects and products of the pharmacy were lost.

Some years later, the building was turned into a pharmacy museum. It displayed a collection of pharmacy objects from all over Transylvania, which had belonged to the professor Gylla Orient.

Some years later, the building was turned into a pharmacy museum. It displayed a collection of pharmacy objects from all over Transylvania, which had belonged to the professor Gylla Orient.

Then Communism collapsed, and the building’s former owners showed up. The fate of the medieval pharmacy was decided in Romania’s courts. By the late ‘2000s the building was returned to the heirs of the former owners. The state could buy it, but didn’t. The responsibility was moved back and forth between the Culture Ministry and the Cluj-Napoca City Hall.

The museum now needs to be evicted. Hundreds of fragile glass, wood and ceramic recipients dating from the 17th century are likely to be moved into a new space, with no history attached. The Baroque paintings will remain, again.

Radu Crisan, the former guide of the Pharmacy Museum, looks terrified when asked about the eviction of the Pharmacy Museum.

“Oh, I don’t even want to hear about it,” he says. “It was a horrible stress for me.” The owners were often coming to the museum, but Radu Crisan was telling them that they should go to the management of the museum instead.

“I know it’s your right, because you are a Hintz, and you even look like the first doctor Hintz,” Radu told one of the heirs. The first Hintz, who owned the pharmacy at the beginning of the 19th century had a beard, a round face and blue eyes. He was a good-looking man, says the former guide. Crisan found the portrait of the old pharmacy owner in a Hungarian magazine.

Radu Crisan retired two years ago. He lives nearby, and when he pases by the museum, he crosses the street, because otherwise, he automatically heads to the museum door and wants to open it.

“No matter how much you love something, when the times comes, you need to step aside,” he says. “I don’t want to be like other pensioners who go to their old work places until the priest leads them to the grave.”

He has accepted to come to the Museum of Pharmacy for a short interview. But he first asked for the permission of Ana Maria Gruia, the new museum’s guide.

Crisan, who will turn 70 next year, wears a white elegant shirt, a vest and jeans. He has allowed himself to wear jeans only after he retired. During his years as the guide of the little pharmacy museum, he was wearing a doctor’s smock, except for the summer, when it was too hot.

He started working in the museum on June 1, 2001. The man previously worked in a biology research institute for decades. As the institute got less and less money, he was forced to find a new job. That’s how Radu Crisan moved from the study of living organisms to the little museum pharmacy, where he immersed himself in the study of old pharmacopoeias. These are books with directions for the identification of compound medicines. Radu was studying the pharmacopoeias when there weren’t any visitors.

“I wasn’t a normal guy,” he says. “Even when a kid visited the museum, I was guiding him in the museum. Not to mention tourist groups.”

He moves through the museum with the same familiarity you move through your own house. Crisan knows every little corner, all the old prescriptions kept in the pharmacopoeias, the uses of products kept from centuries ago.

He moves through the museum with the same familiarity you move through your own house. Crisan knows every little corner, all the old prescriptions kept in the pharmacopoeias, the uses of products kept from centuries ago.

His favourite part of the museum is the Oficina, which was the main room of the old pharmacy. The room has the original Baroque mural paintings from the 18th century, with heart-shaped medallions. When he first entered the room, he felt he had arrived in a sacred space. It was “like I entered a church,” Radu says.

The Oficina had the role to impress the customers, says Ana Maria Gruia, the museograph who is currently in charge of the Pharmacy Museum.

“The pharmacists are the first who invest in marketing and retail in the 17th century,” she explains.

The 33-year old woman, who specializes in art history, started working here in 2014. She was fascinated by the museum’s manually hand-crafted century-old jars. There are “thousands of ceramic vessels made of porcelain, majolica, tiles, transparent glass bottles, milky glass bottles,” she says. Ana Maria accompanies her presentations with hearty laughs and down-to-earth comments.

The first pharmacies in Transylvania opened in Saxon cities. The Saxons are a people of German ethnicity, who built hundreds of towns and fortified churches between the 13th and 15th centuries in Transylvania. These included Sighisoara, Sibiu, Brasov, Medias, Sebes or Bistrita. Hungarian kings, who then rules Transylvania, brought German colonists in this area to defend the southeastern border of their kingdom.

“In Transylvania, the first pharmacists were Saxons, Hungarians, Jewish, only later Romanians, and very late, women,” Ana Maria Gruia explains.

The old Cluj pharmacy, now hosting the museum, was privatized in the 18th century. Previously it was a “city pharmacy”, belonging to the local administration. The privatization was part of a larger process taking place at the time. In 1699, the Ottoman Empire conceded Transylvania, Hungary, Croatia and Slavonia to the Austrian Empire.

The pharmacy’s first private owner was Alexander Schwartz. However, his nephew Tobias Mauksch, who took over the pharmacy in 1752, was the most famous owner.

Tobias Mauksch was born in Slovakia in 1727. His uncle Alexander Schwartz brought him in Cluj-Napoca when the boy was 14. The young Tobias then moved to Stuttgart to get a degree in pharmacy. He returned to Cluj when his uncle died, and took over the pharmacy. He was about 23-year old, says Radu Crisan, the museum’s old guide. Tobias was married twice, had 18 children, but not all survived. One of his nieces, Matilda, married with the Lutheran priest called Hintz Gottlieb. That’s how the pharmacy’s ownership moved from the Mauksch family to the Hintz family.

Tobias Mauksch had a strong competition from the Jesuits who were also running pharmacies in Cluj-Napoca. They were selling products at lower prices, or even for free for poor people. Mauksch submitted a series of complaints against the Jesuits at Vienna, which was the center of the Habsburg empire. The more so, he invested in the image of his pharmacy to attract more customers.

Later in his life, Tobias bought a pharmacy in Targu Mures for one of his sons, who was only 11-month old. Tobias left him a series of advices on how he should keep his business running. He told his son to be careful with his assistant and servants. They shouldn’t waste their time at parties or cause scandals that can damage the pharmacy’ reputation. Around Christmas, the pharmacist should pay a short visit to the doctor to make sure that he’ll send him customers, the father advised his son.

It was similar to how things work nowadays, Ana Maria explains. Instead of offering the doctors trips or pencils as presents, the pharmacist would bring the doctor a few lemons every Christmas, which were exotic back then. “Six lemons for the more experienced doctors, and three, for those who had less experience,” the guide says.

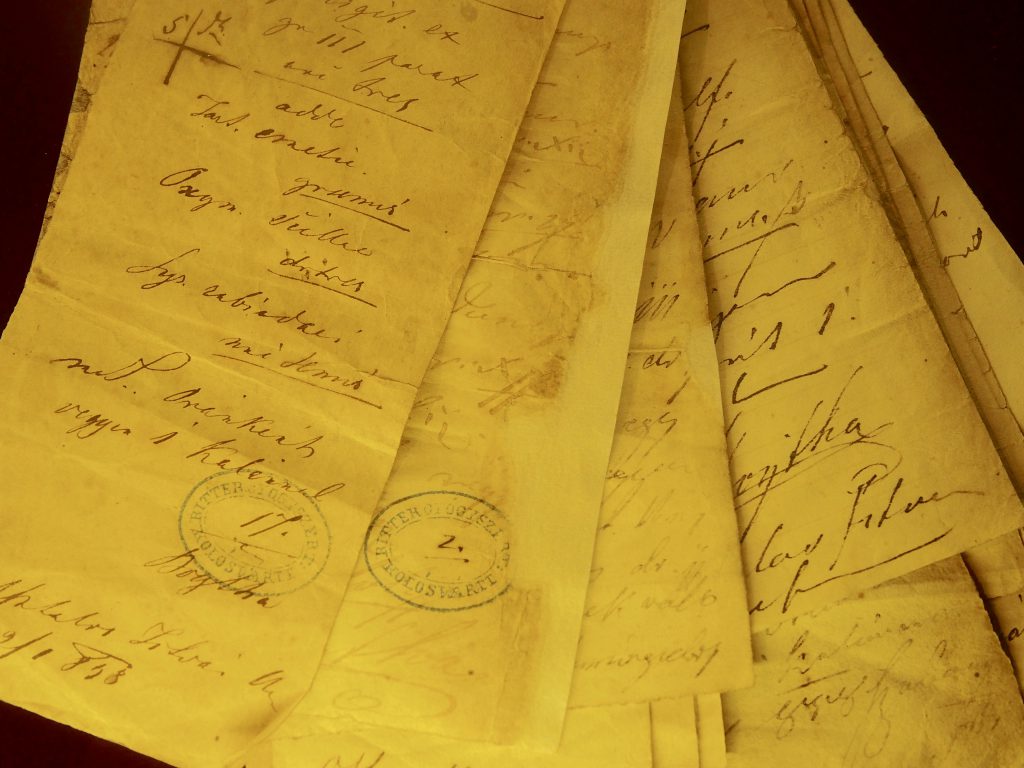

However, the son died and couldn’t take over the pharmacy bought for him, nor use the advice given by his father. But Tobias Mauksch’ words remained in a document which is now kept at the Pharmacy Museum.

Lizard dust and waiting time

Lizard dust and waiting timeSome of the most exotic products sold in the pharmacy included lizard dust. The substance was made from the pulverized bones of a lizard originating in Asia. The pharmacists had different opinions about its effects. Some were saying that the lizard dust was a great aphrodisiac for young women whereas others considered it a good diuretic product.

The visitors listen fascinated Ana Maria’s explanations. It’s like time travel, and this is very much influenced by the space itself. The narrow stairs, the Baroque-adorned Oficina, the dark rooms are all essential parts in this history puzzle.

Asked what he thinks about the idea to move the headquarters of the pharmacy museum to a different building, the former guide Radu Crisan says with an almost frightened voice :

“Don’t even mention this! Which is the best space for the a pharmacy museum? The oldest pharmacy in Cluj.”

Both Ana Maria Gruia and Radu Crisan say it would be extremely difficult to move all the fragile objects, the old pharmacopoeias, the century-old wall cabinet; not too mention the original mural paintings.

The fate of the museum is, though, in other hands. They can only wait.

Eviction is nowadays a possible scenario for several of Romania’s museums. The Romanian Association of Ethnological Sciences warned back in 2013 that many museums can lose their headquarters.

The Cris County Museum, which was located in the Baroque Palace in Oradea, was restituted to the Roman Catholic Church. The museum closed in 2006 in order to be moved to a new place. Ten years later, solutions are still searched. The museum’s website has a section called “Save the Museum”. The Baroque Palace is considered the most important Baroque building in Romania.

The buildings hosting the Museum of Art and the Museum of Ethnography in Brasov were restored to the Evangelical Church in 2008 and 2011. The owners and the authorities couldn’t agree upon a selling price, nor about a monthly rent. The museums are now waiting to see what will happen next.

The Museum of the Gumelnita Culture in Oltenita, displaying representative pieces of one of Romania’s oldest cultures, was restored to its owners in 2005. The museum still operates in the old building, but it can be kicked out any time.

The law grants the authorities the pre-emption right for historic buildings. If the owner decides to sell a historic building, the state is given priority in buying it.

In November last year, the Cluj-Napoca mayor Emil Boc told in an interview for the local radio station Radio Cluj that the local municipality had used its pre-emption right for the building hosting the Pharmacy Museum, but the owner asked for a price that was too high. “The Pharmacy Museum has been allocated a space in the center of Cluj,” Boc said.

The final price asked by the Hintz heirs for the whole building was around EUR 800,000, according to sources in the museum.

Carmen Ciongradi, the interim director of the National Museum of Transylvanian History, which runs Pharmacy Museum, said that they are now waiting to see what decisions the authorities will make, whether the owners still want to sell the building, or whether they decide only to rent it.

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com