The lesson we learn from watching storks in their Romania nest

This summer I drank my coffee every morning while watching white storks in their nests. I wasn’t the only one. And everyone was hooked.

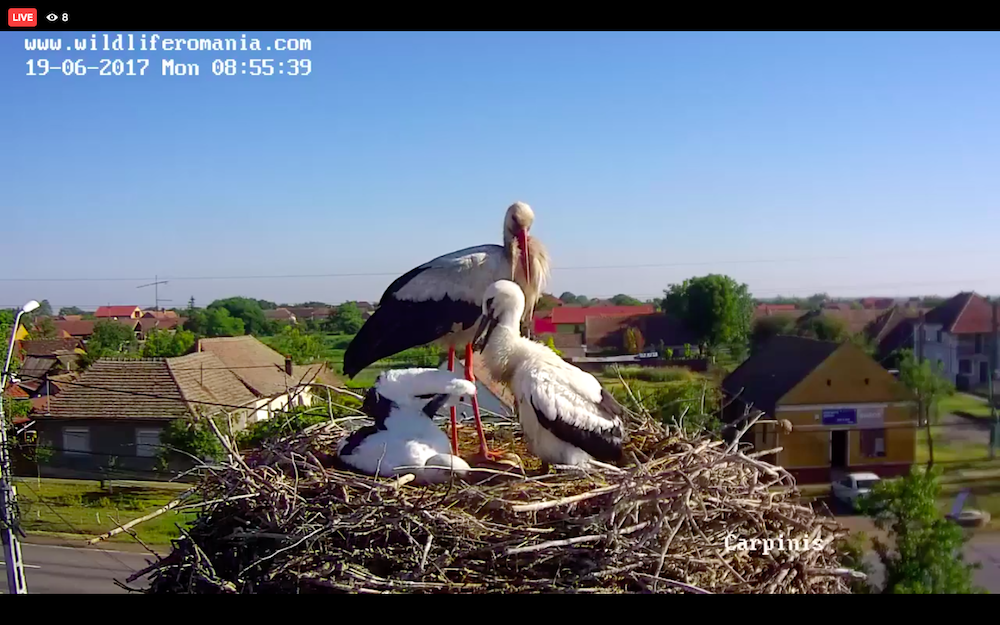

I was in Bucharest, and the white storks were in their nest in a village in Western Romania. We were all watching them via live streaming on the internet. I came across the page by chance, on social media.

In August, when it was clear that the storks would soon leave the nest to migrate to Africa, people watching shared emotional comments: the birds will be missed...

“People have forgotten that we are not alone in the world and we share this habitat with a bunch of other neighbours,” says Cristian Ilea, the man who initiated this WildLifeRomania.com project.

At the other end of the phone line, right from the beginning of our conversation, he answers some of my questions: What do people get so hooked to wild animals? Is that ok? Why did Cristian start the project? Does he make any money?

At the other end of the phone line, right from the beginning of our conversation, he answers some of my questions: What do people get so hooked to wild animals? Is that ok? Why did Cristian start the project? Does he make any money?

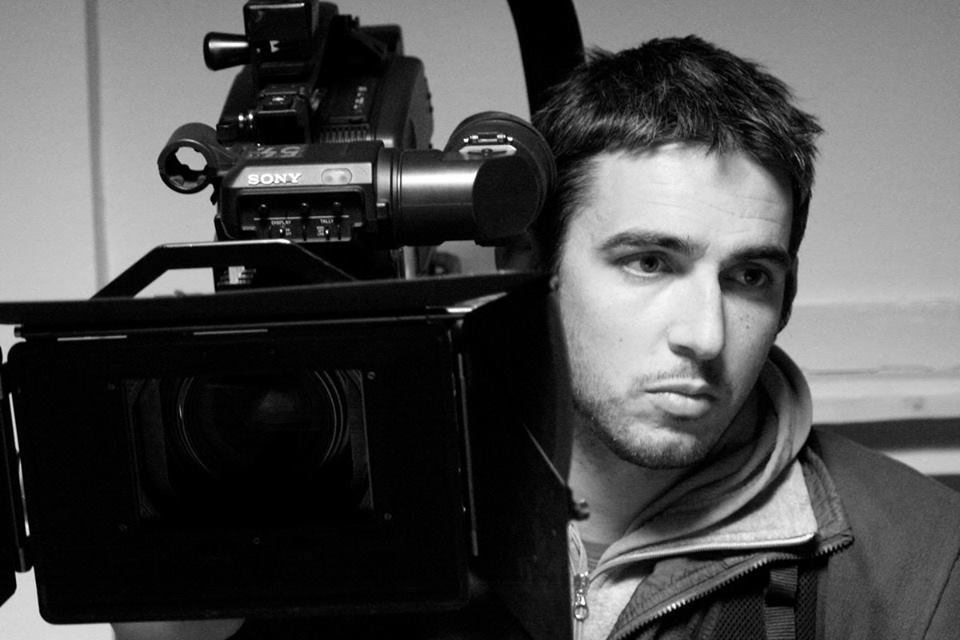

Cristian, who is now 40 and makes a living as a camera operator, had lived in Bucharest for 12 years, but moved to Timisoara, in Western Romania, eight years ago.

“I don’t waste time in the Bucharest traffic anymore. I’ve saved two hours every day, which I dedicate to the WildLife project,” he says.

Inspired by people he met while attending the Wildlife Film Academy in South Africa, Cristian decided to install the first camera in 2013, at a stork nest in Carani, Timis county. He chose Carani, because it had one of the oldest nests in the county. People in the village remember that the nest was already there in the ‘30s, when they were going to school. There are only seven nests left that are built on chimneys in the Timis county, according to Ilea. Most nests are built on high-voltage pylons.

Inspired by people he met while attending the Wildlife Film Academy in South Africa, Cristian decided to install the first camera in 2013, at a stork nest in Carani, Timis county. He chose Carani, because it had one of the oldest nests in the county. People in the village remember that the nest was already there in the ‘30s, when they were going to school. There are only seven nests left that are built on chimneys in the Timis county, according to Ilea. Most nests are built on high-voltage pylons.

One year later, the stork male didn’t return to the Carani nest. He could have starved or he could have gotten shot dead, as storks pass through conflict areas, Cristian explains. But his absence meant that there would be no stork cubs that year. It is very difficult to form a new couple. Storks form couples at the nest, but when they migrate, they leave separately. The female and the male meet again at the nest, several months later.

Cristian decided to install a new camera at a nest in Carpinis, Timis county. The nest is built on the chimney of a house owned by Ion Haiduc, a man from the village. He is very proud that the storks are in his yard. He takes care of the camera and the equipment, and supplies power without asking for any money.

“It’s easy to watch a monitor and feel empathy for what’s going on there,” Cristian says.

“It’s easy to watch a monitor and feel empathy for what’s going on there,” Cristian says.

People tend to overlap human behavior on bird behavior. They identify a lot with their story. They look at the birds and they see a mother, a father and children, Ilea explains. If cubs haven’t received any food for three hours, some people start panicking.

But life is much tougher for wild animals. The fight is cruel from a human point of view. If one of the cubs is sick, one of the storks will kill it and will throw it. Some people get very upset with that. They start hating the storks. But storks are not pets or humans. They are a different species, with different rules, Cristian says.

“For me, the project is about education and less about entertainment,” he adds.

One summer, two stork cubs got very sick after a strong rain. They were lethargic, and the parents weren’t in the nest. People were watching this online feeling helpless. They asked Cristian to go to the nest and take the cubs to save them.

He summoned the firefighters and they were ready to intervene, but the parents finally returned. The cubs died. The adult birds organised a sort of funeral ritual. They covered the cubs with hay and performed a dance, which was similar to the one performed when the male and female meet at the nest. They clattered and shook their heads. After a day, they threw the cubs from the nest.

Cristian took the cubs’ bodies to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine for an autopsy. The cubs had died of pneumonia. Doctors also found very large shards in the gizzard at the autopsy. The cubs would have died anyway after growing a little more because of these shards, doctors said.

The male stork brought the shards with a glass wool that he found at the illegal dump site near the village of Carani. Birds bring in all kinds of materials to build their nest. They constantly refurbish their nest. Once the storks brought a bag of chips to the nest.

“When people throw the garbage some of the garbage gets into the storks’ nest,” Cristian says.

There are several people who help Cristian keep this project alive out of sheer passion. A sort of semi-voluntarism, he says.

There are several people who help Cristian keep this project alive out of sheer passion. A sort of semi-voluntarism, he says.

I ask him if the project is profitable by any means, because it’s popular on Facebook. He has about 2,500 unique visitors on the website every day. The player streaming images from the Carpinis nest has almost one million views.

Cristian laughs. It’s the other way around. He doesn't make money, but he spends money from his own pocket to keep the project running. This year he’s launched an appeal for donations. He managed to raise 2,500 euros out of a quite modest goal of 5,000 euros.

“I’m not interested in making money out of this project. It would be great if the project could self-finance, so I wouldn’t have to spend money from the family’s budget,” he says.

For him, this project is about educating people to understand nature; to see what’s beyond the edge of the city, beyond their own house, beyond the boundaries with which they have become accustomed. People are comfortable in the space they have created, whether it’s home or work or a bar where they often go. But there’s so much world to see.

Last year Cristian installed a camera to monitor the saker falcon (Șoimul Dunărean in Romanian), an endangered species.

Last year Cristian installed a camera to monitor the saker falcon (Șoimul Dunărean in Romanian), an endangered species.

More common kestrels (vânturei in Romanian) also came to the nest.

The saker falcons are less popular than the storks. They sometimes bring prey to the nest, such as gophers. The image is bloodier. People prefer pigeons, storks and animals that are easier to humanize as representation.

Cristian also installed his first bird feeder in 2015.

Winter is coming, so in the next days Cristian will bring food to a bird feeder in Oradea, Western Romania. The device is in the yard of a man working at the post office, who is interested in birds. Instead of growing corn or sunflower, the man plants herbs in his garden to feed birds and arranges places in the garden to catch wild mice for birds. When the snow falls, the birds can’t find seeds alone. Cristian and the post man are there to help.

You can support this wildlife project here.

By Diana Mesesan, diana@romania-insider.com

(photos: Pixabay, screenshots, Cristian Ilea)

Related stories:

Romanian Ornithological Society launches white stork census app