A look at the 80’s generation in Romanian photographer Andrei Bîrsan’s latest exhibition

Andrei Bîrsan has always enjoyed taking photos. Carrying his camera with him almost everywhere, he amassed a large collection of photographs depicting the transformation of Bucharest through the years and its people. He is known as a visual chronicler of the city, having started the association Bucureștiul meu drag (My Dear Bucharest), with a popular Facebook page and platform of the same name where photos captured in time by Bîrsan and others make up a ‘family album’ and visual archive of the city. He also founded the Center for Visual Memory, an initiative for anyone looking to get to know, visit or contribute to developing the city’s visual story.

At the same time, he has always been interested in photographing people. “My photos of the city have people in them. Most of them feature people,” he explains. This was a selection criterion for the photos included in the recently-opened exhibition The ‘80s Generation: A Photographic Journey. The images had to depict people to be included, in seldom photographed places and contexts.

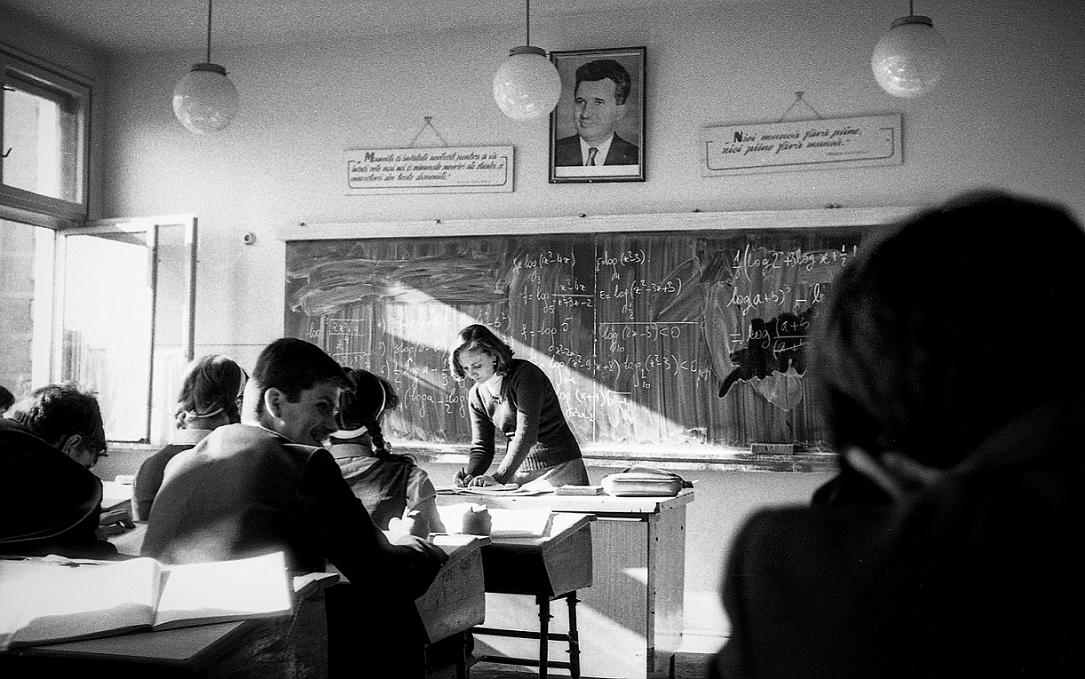

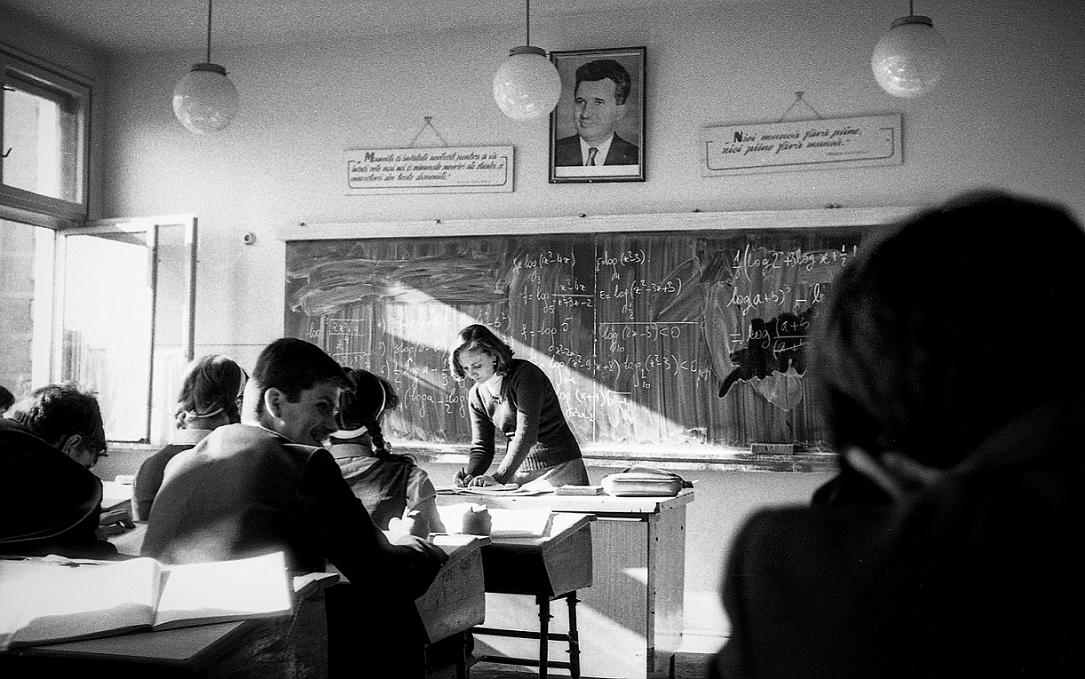

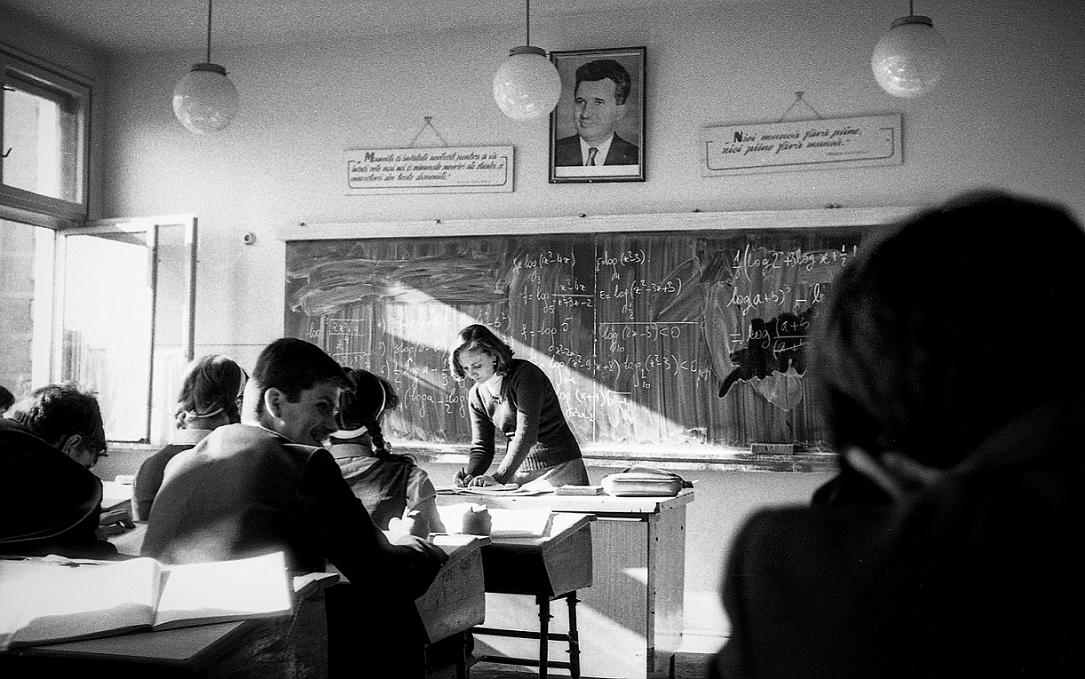

The photos show scenes happening in high school or university throughout the decade of the 1980s: students playing liniuța - a game where players through coins against the wall, and the one who hits closest is the winner, attending sessions of PTAP - the Communist-era program designed to prepare the youth to defend the country, or harvesting potatoes, another part of Romania’s educational reality at the time as middle school pupils, high schoolers and university students were expected to perform various agricultural labours in a show of patriotism. The "voluntary" practice students had to do sometimes entailed cleaning up the streets from snow, a work where teachers joined in too, as captured in another photo in the exhibition.

His colleagues, whom he remembers fondly, didn’t mind being photographed, he recalls. It was the teachers he had to be careful about, but even they are characters in some of the images. He attributes part of the relative ease with which he could take the photos to the small size of the camera, a basic Smena model. “They probably thought nothing would come out,” he says.

This wasn’t the case when taking photos of the city, in areas where buildings were being demolished as Nicolae Ceaușescu’s urban redevelopment frenzy had reached peak levels. He had his camera confiscated twice while taking photos around the site of Casa Poporului, the current Parliament Palace, and another time at the District 3 Tribunal, close to Sfânta Vineri Church. “These were areas where demolition works were taking place, so it was, in a way, predictable,” he explains. Having his camera confiscated was when he understood “the city needed to be photographed as a form of memory because it was changing.” “I realized I could do something to show how it looked.”

The 80s generation

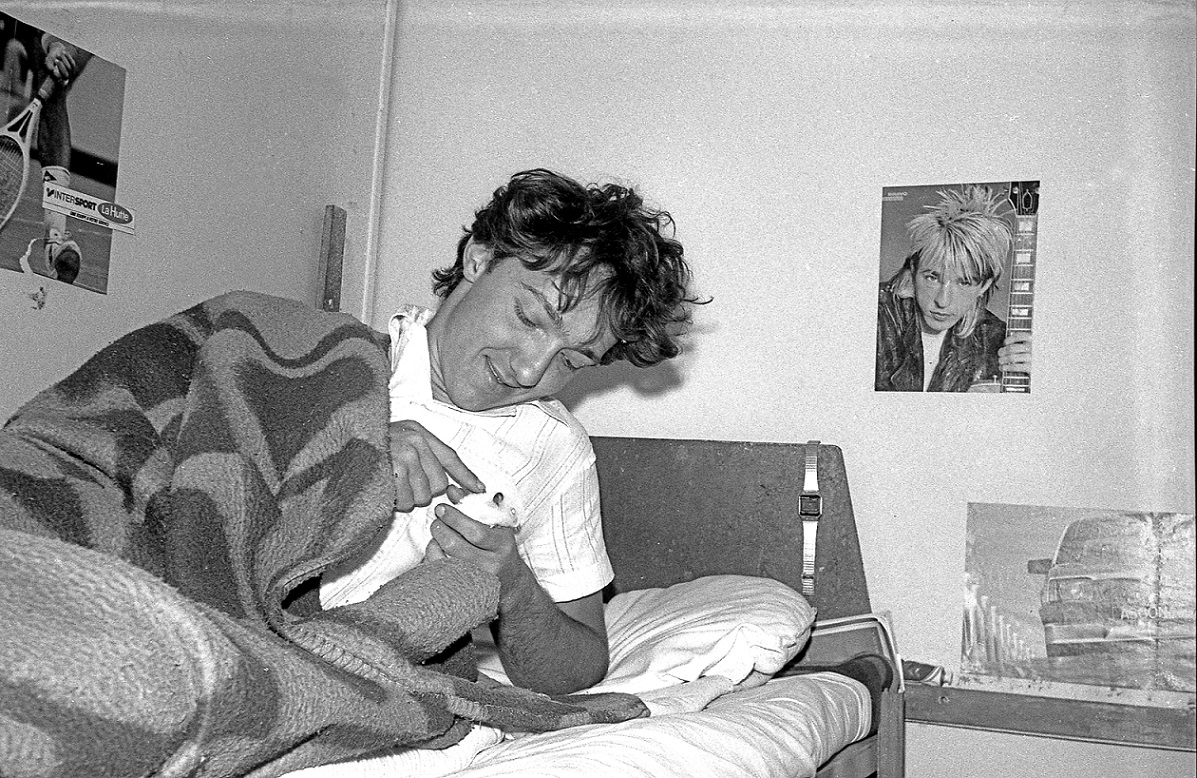

It’s the colleagues and teachers that are the main characters in the photos: Tomi, happy to have passed an exam; diriga, the classroom’s coordinating tutor; or the colleagues out doing agricultural practice. They are part of a positive side of the 1980s, a period of “youth and lack of worries.” “Parents helped us not to have any worries.” Although he doesn’t recall enduring hunger, he does remember the cold. “The cold was terrible.” As Nicolae Ceaușescu decided the country had to repay its foreign debt, a period of dire shortages followed, with food, gas, and energy rationalized.

As the pressure of cooking gas was very low, dinner would happen very late in the evenings because the food took longer to cook, and sleeping with extra layers of clothes on was the norm for many. It wasn’t just homes that were cold. He remembers taking his wife, Mihaela, to the cinema, where the film’s main character ends up freezing to death, while the couple endures very low temperatures in the cinema hall as well.

Befittingly, the exhibition is on display at Undeva în Comunism, a museum that opened last summer in Bucharest’s Old Town. The museum invites the public to discover how Romanians lived during the Communist period and explore key moments of the period in a setup dotted with items that could be found in many Romanian homes at the time.

The photographer is clear about the difference between the nostalgic look to a time of youth and Romania of the Communist 1980s, a period of severe deprivation. “We were trying to be normal. There’s no need to be nostalgic about that time; it’s absurd. It’s the nostalgia about the youth, about some beautiful moments.” One of those moments: watching pirated movies on a rented VCR in the university dormitory. “We watched five-six films in one night. Some of the tapes had been recorded over so many times that you could barely distinguish anything,” he recalls.

He is currently working on an album of photos he took in the 1990s in the mountains, where he would go every summer while at university. Another work in progress is an album covering the period between 2000 and up to and including 2007, when Romania joined the European Union, a moment he describes as fantastic. “There’s a huge difference between 2005-2007, when the Dacia Logan appeared, and the previous period. The entire city changed. Romania changed completely, for the better.”

“If you look at the photos I took over time, I captured ‘the nothing’. They are banal. They became interesting with the passing of time, valuable, but they are banal,” he says, rejecting labels of praise.

Meanwhile, he hopes those who visit the exhibition will “find themselves in the photos” and the various situations they show.

The exhibition is open until February 20th at the museum Undeva în Comunism, in Bucharest’s Old Town (6 Covaci St). Access to the exhibition is based on the museum ticket.

A selection of photos by Andrei Bîrsan is available at Bucurestiulmeudrag.ro. He has published several photo albums, including Iubita mea Mihaela (2021), the winner of the Antalis Awards 2020 jury prize, Trecut-au anii. Bucurestiul de ieri si de azi (2019), and Frumusetea revine pe Lipscani? Is Beauty Coming Back on Lipscani (2017). Among his solo exhibitions were ones dedicated to the 1980s, Vama Veche, and Bucharest. His photos of Bucharest were also included in ‘then and now’ exhibitions, more recently in an outdoor display at the Museum of the City of Bucharest (Suțu Palace) in September 2023.

(All photos courtesy of Andrei Bîrsan)

simona@romania-insider.com