A young Czech documents Romania’s Communist past and brings an old cinema back to life

The photo of an abandoned cinema in Romania, which was able to host up to 900 people. Then, an abandoned buffet-bar “which looks like somebody had to leave it immediately and take just the necessities”. Both posts share the hashtag #abandoned. And both are on Jakub Charousek’s social media wall.

These are buildings most people normally ignore. Many of them were built during the Communist era. We let them crumble. We don’t care. But for Jakub, these buildings have historical and artistic value.

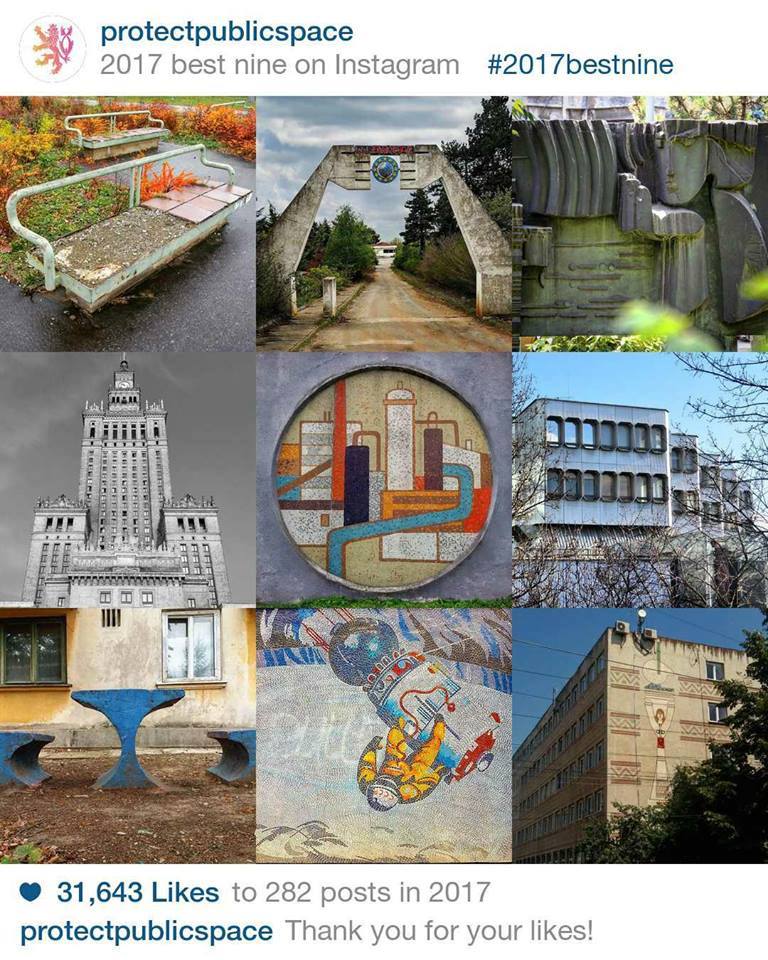

The 25-year old Czech-born political scientist, currently working at the Czech Embassy in Bucharest, started documenting these Communist buildings in Romania one year ago, together with František Zachoval, the director of the Czech Center in Bucharest. They take pictures of buildings they see during their walks or find old photos in the archives. Later they post them on an Instagram account called “Protect Public Space”. They also collaborate with the Romanian artist Roberta Curca, who now writes her PhD on these buildings.

I meet Jakub at a cafe in Bucharest. I don’t recognise him right away because he doesn’t have a strong online presence. Almost no pictures at all. His Twitter profile has a drawing of a smiling man, wearing glasses. I match it with a slim, very tall guy waiting in front of the terrace.

He first came to Bucharest as an Erasmus student in 2016, where he met his girlfriend. Jakub later decided to move here for good. He first did an internship at the Czech Center and then took on a job in the economic section of the Czech Embassy in Romania.

Hundreds of pictures of facades, welcome signs, seaside hotels, drinking fountains, post offices or restaurants flood your screen as you scroll down through the project’s Instagram.

“Protect Public Space” is based on a similar project in the Czech Republic, which tries to map Socialist art in former Czechoslovakia. As in Romania, valuable buildings are left to fall apart. Many of them were built as the result of a law providing that 4% of all investments in infrastructure had to be poured into art, Jakub explains. The Barrandov Bridge, for example, built over the Vltava river in Prague, has massive concrete sculptures next to it. They were built with money from the bridge’s construction.

“Protect Public Space” is based on a similar project in the Czech Republic, which tries to map Socialist art in former Czechoslovakia. As in Romania, valuable buildings are left to fall apart. Many of them were built as the result of a law providing that 4% of all investments in infrastructure had to be poured into art, Jakub explains. The Barrandov Bridge, for example, built over the Vltava river in Prague, has massive concrete sculptures next to it. They were built with money from the bridge’s construction.

The Barrandov Bridge, as well as many Communist buildings in Bucharest, are described as brutalist architecture. The style originates in the modernist architectural movement of the early 20th century. Although many people tend to associate it with Socialist countries, brutalism was popular in English-speaking countries, Brazil, Japan, as well as the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union.

“People are apriori saying This is Communist. It has to go out. Even though it has artistic value,” explains Jakub. “It’s Communist, let’s destroy it. Let’s build something new.”

The project’s idea is to show people what is around. It’s about looking at these remnants of our past without an ideological lens, but rather with historical curiosity.

It is not only an ideological vs. artistic battle. There is often an economic stake, Jakub says. He gives me the example of Transgas, a brutalist building in the center of Prague, for which architects, art historians, government employees and real estate developers have fought in the last years. The developers have won. Art historians from Czech universities requested Culture Minister to prevent its demolition, but the Czech Ministry of Culture approved the demolition last fall. A new office complex will be built there.

This summer the Czech Center will restore Cinemascop, an old, abandoned cinema in Eforie Sud, a resort at the Romanian seaside.

“We have the keys to it. It is abandoned. Falling apart. We would like to put it in a state to welcome people, to clean it, to put benches, to have there a short film festival in the summer, to screen movies there,” says Jakub.

“It’s important to show people that it’s possible. That you really don’t need a lot of money,” he adds.

During Communism, Czechs used to go to their cottages in the countryside during the weekends and not care about the things around, Jakub explains. “I think it was the same here. People were hiding differently, but still. And they didn’t know that you can make it better if you just plant some flowers in the neighbourhood.”

The young man is optimistic that people in former Communist countries can rebuild their communities, escape their isolation. “It just needs time and good examples. But mostly time.”

Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana.mesesan@romania-insider.com

(opening photo by Diana Mesesan; interior photo: print screen Instagram)