The track to success: How Romanian David Popovici became the new star in world swimming

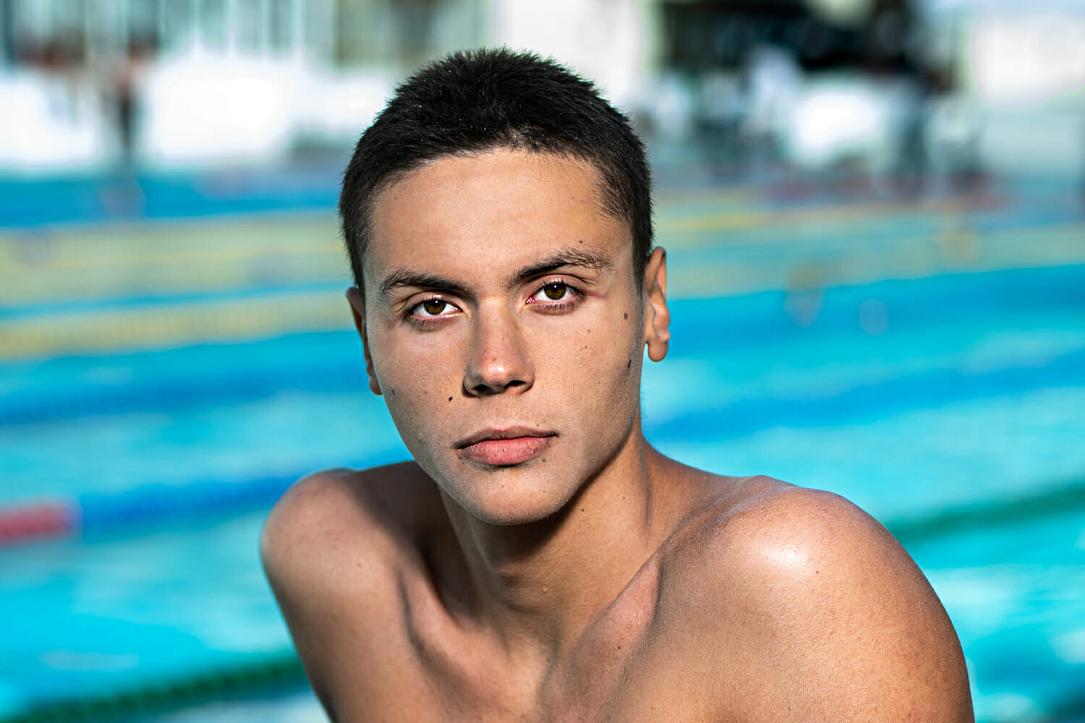

The teenager by the pool wants to become the world’s fastest swimmer. He is 17 years old, 1.90 meters tall and sports a roguish smile. He smooths his swim cap over his buzzcut and hides his brown eyes behind goggles. He plants his feet firmly on the starting block, stretches his long arms, with a 2.05 meters wingspan, above his head and shakes them a few times.

The teenager is David Popovici and he’s been at practice since 6:30 AM, as he is every day. The routine on this Tuesday in May includes four 100 m freestyle sprints. On the starting block, he bends his right leg in front and his left in the back, making a 90-degree angle. He breathes, bends down and, when he hears Aaand followed by a short whistle, he plunges and disappears under water.

The whistle is blown by Adrian Rădulescu, the 32-year-old coach who walks along the pool side, stopwatch in hand, carefully observing his arm strokes chopping through the water, his kicks stirring up foam, the way he holds his elbows. He sees in David the same ease in swimming he spotted when the boy was 9 and he started coaching him. After the first 50 m lap, he walks back alongside David, stops the watch and jots down the time in a hardcover notebook.

Rădulescu had warned David and his training partner, Dragoș Ghile, that today’s set would be intense, competition-grade and grueling. Major competitions take place this summer, including his last junior meets, so this is the time to swim all he can.

After the first hundred meters, David stops at the end of the lane panting. His smile is gone. He’s got a five-minute break before the next sprint, so he climbs out of the pool and resumes his position. Before diving back in, he slaps his arms and legs a few times, the way he does before races. He did it last summer in Tokyo, where he was the youngest competitor in two Olympic finals and the fourth-best in the world in the 200 m freestyle.

Last summer he also became the fastest 100 m swimmer under 18 in history. In Romania, he’d been at the top for a few years already but as of last summer he is no longer just a high school kid who swims fast – he is the swimmer hailed as a revelation, a prodigy of Romanian sports, a world swimming phenomenon. Other swimmers say his is a talent that comes around once in a hundred years.

The birth of a champion

David started swimming, at Lia Manoliu pool in Bucharest at the age of 4, the same way all active children do: taken by his parents who were hoping to pick him up all tired out so he would sleep more, but also at a doctor’s recommendation to correct early stage scoliosis. The water was the environment in which his long and lithe body felt right at home from the start and which gave him confidence. He also enjoyed the fact that at Bucharest Sport Club, the private club where he took his first lessons, swimming was play. But he liked to swim at his own pace and his first coach called him by the nickname his colleagues had given David because of his shoulder-length hair: “Fairy boy, are you watching the clouds or what?”.

He wanted to continue to swim competitively, so his parents enrolled him in a school with an athletic program, Emil Racoviță. Because they were not happy with the chemistry their son had with his coach, at 9 they asked him if he wanted to continue someplace else. He chose Aqua Team București (now Navi), a club founded in 2007 by Cătălin and Iulia Becheru, two children’s coaches with good results. It was the best children’s swimming club in the country and David told his father: “I want to win medals too”.

The right coach

It was there that in 2013 he met “Mr. Adi”, as he still calls coach Adrian Rădulescu. A former swimmer with a PhD in athletic performance specialized in swimming, Rădulescu started out at the club as a volunteer, when he was a student, recommended by Pierre Joseph de Hillerin, former manager of the National Institute for Athletic Research. He told the club founders he had a student who wanted to coach at the Olympics. He first taught swimming lessons and physical fitness, then took over an athletic team that included David.

He found a restless and mischievous child who was easily bored, especially when he had to swim long distances. He would stop and play with his goggles, ask to go to the bathroom, say his head hurt, or his shoulder, or his stomach. Still, when he wanted to, he swam incredibly fast for the amount of training he did, said Rădulescu. “Minimum effort, maximum impact.”

“You could tell it wasn’t just because he was taller. OK, he was tall, but so were others. He wasn’t the strongest. He couldn’t do a push-up, others could do 100. There was clearly something else at play there.”

The challenge for Rădulescu was to get him to use his competitive streak in training as well. He understood he was the type of child who needed things explained, you couldn’t make him swim 10 laps just because you said so. He gave him materials to read about training and had him summarize the main ideas. He explained why he was feeling certain things and what happened inside his body so he would understand why he felt sick after a workout.

“He never reprimanded him,” said the swimmer’s mother, who liked the fact that Rădulescu didn’t try to change him. He let him play. They joked together. They listened to music. He always tells him to have fun and David brings this up in interviews like a mantra.

“Before I met Mr. Adi, I didn’t know swimming was fun,” David told me at the end of a training session where he got out of the water a few times between sets to change the song that was playing. Subcarpați, Kazi Ploae or Specii often boom from the speaker he sometimes brings along from home.

Coached by Rădulescu, he started winning and he liked it. At the age of 10, he broke his first national record, in 50 m backstroke – a 24 year-old record held by Dragoș Coman, a 2003 world bronze medalist. He knew then he wanted to break as many records as he could, and has broken over 30 so far. At 14 he became the fastest swimmer under 15 in the history of the European Youth Olympic Festival, swimming 100 meters in 49.82 seconds.

Parent support

Rădulescu said there wasn’t a particular moment, a competition or a national record that revealed David’s potential, instead it was more of a process during which he saw him responding well to the challenges and the bars he set. It’s hard to see a 12-year-old kid and say he’s the next star in swimming, and he’s seen many talented ones lose their way. “There’s a lot going on in life, from your relationship with your family, the situation at home. (…) A lot of things can sidetrack you.”

What kept David on track, his coach thinks, was “first and foremost” his relationship with his parents, Mihai and Georgeta Popovici. They never said to him: “You didn’t do well in the competition, you’re grounded.” They didn’t collect medals or reward him with prizes, phones or money, as they’d seen other parents do. But they always stopped to eat at IKEA after swim meets, regardless of whether he’d won or lost, because David liked the cake there. At home, they don’t talk about swimming, time marks or training – before he qualified for Tokyo, his mother didn’t even want to hear the word sushi –, unless David wants to tell them anything about it. They care more about how he felt and whether he had fun than the time or number of laps. “That’s between him and Adrian.”

What they did was always believe in him. Although he’d never talked to any coach about his son’s potential, his father knew when he was about 11 that he would become an exceptional athlete. He was impressed by his son’s attitude. How he never let defeat bring him down. He didn’t cry, he wasn’t disappointed, he wasn’t even upset when he got disqualified for diving into the pool too early at a contest. Before competitions, he performed card tricks for his mates and he’d been nicknamed The Magician. And, regardless of the outcome, he always went in it to win in.

“He’s more consistent than we could ever be,” said Mihai Popovici, who works in sales but has become an expert in nutrition, unprocessed foods and additives. When they learned it’s best for David to eat two hours before practice, his parents started waking up before him, at 4:30 AM, to make him breakfast, which they serve to him in bed so he can sleep one more hour afterwards. At swim meets, the other parents suspected they were doping him when they saw them mixing his milk with cinnamon and honey, his favorite drink, in the trunk of their car.

As the costs of training increased, David’s father wrote hundreds of emails and made countless phone calls to find sponsors. “Very few replied but it takes hundreds of such gestures of reaching out to find one, two or three sponsors. Many around us didn’t do it, they were resigned from the start with the idea that it was impossible. There is no such thing. It’s possible, just not right away.” (Sensiblu, Moller’s, CEC and BursaTransport were the first brands to support him and in 2015 he won a grant offered by the Bucharest Community Foundation. BursaTransport still supports him today, along with Edenia, MedLife and Arena.)

When he was 8, David told a coach he wanted to compete in the Olympics, so his parents made him a cake and printed a T-shirt that said Tokyo2020, the first Games for which he would have been eligible to qualify. They made mascots and invented songs. At competitions, they wore T-shirts that said Kahuna’s mom and Kahuna’s dad, another one of David’s nicknames, a Hawaiian term for magician. They moved closer to the pool, they paid for trips to national meets and his mother, a psychologist by trade, took an anti-doping course so she could check his pills and supplements.

These are sacrifices no one sees, said Rădulescu, and fewer and fewer parents are willing to make them. From his group of 20 children, David is the only one still swimming competitively. The children’s schedule is busy with tutoring, their parents are at work and can’t bring them to practice during the day, can’t afford to support them any longer or expect to see results too soon. “Parents want certainty. And sport – as in David’s case, at least until July 2021 – is uncertain. People can’t wait.”

Mihai and Georgeta Popovici don’t see their efforts as sacrifices but as something they need to do for their son, to see him happy. Not just take him to practice but help him have as normal a life as possible, even though his schedule must be balanced down to the second to include his two training sessions, psychical fitness – at 6:00 AM, one hour before going into the pool –, rest, school, time with his girlfriend, and his rare get-togethers with friends.

High expectations

After last summer, people are expecting him to bring in increasingly spectacular results. In November, he won his first senior medal, gold at the European Short Course Swimming Championships (25 meters). Although many of his rivals did not compete, he was happy “to make a little history in Romanian swimming”, as this is the first short course gold for Romania. He then competed in the World Short Course Championships but didn’t make the finals. This spring, he dominated the National Championships, the Romanian Cup and a junior meet in Slovenia.

If training goes according to plan, a medal at the World Championships in June – where Dressel is again top favourite – “is not out of reach”, thinks David. But it’s not an essential goal either.

It’s a step in the long-term project he is building together with his team. It’s a milestone that will show them how he has progressed, how he has learned to use the strength he’s gained in the past year – which can be helpful but also cumbersome – and which way they are heading for the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris, where they target the podium. But also further than that, because he wants to compete in the 2028 and 2032 Olympics too.

“Everyone now expects him to come in at number one at the World Championships,” said Rădulescu. “It’s possible but, on the other hand, he could very well not be number one, he could be number 12 at the World Championships and he could win the European Championships two months later. He might not break the world record at the World Championships, he might break it at the World Juniors. There are so many fine-tuning parameters, you reach this point where everything must be perfect.”

He’s seen David swim every day since he was 9 and doesn’t make too big a deal out of his junior world records, or the fact that he is faster than Dressel was at his age, or people saying he is a freak of nature. For now, all that just sounds good. For now, he’s not impressed with what David is doing in the pool today.

But what he could do in the future is truly impressive. What he could be able to do in time, if all goes according to plan, if he fulfills his potential, this word so often used in sports and that depends on so many factors, so many people, and so many details.

editor@romania-insider.com