The Romanian boy who overcame the dark side of an international adoption

In his early childhood, he was Nicolae Burcea, but friends called him Nicu. After being adopted, the boy’s name became Nicolae Butler, and everybody in the US called him Nico.

The 23-year old man now uses Nicolae Burcea when he writes books or in casual conversations, but he’s still a Butler in official documents. Officially, though, he’s no longer a member of the Butler family.

“I like to think about it, to say that I’m a new generation Charles Dickens character because everything is an up and down. (...) The amount of luck I get is incredible especially given the odds,” says Nicolae.

In a hours-long Skype interview, Nicolae tries to disentangle his life story, to explain it to a stranger. It’s not the first time. He’s written a book about his early childhood in orphanages in Romania and he’s told his story hundreds of times. But despite the suffering, the young man feels that there could be a meaning, that his story could inspire others.

***

Nicolae Burcea was born in December 1993 and placed in the “Sfanta Ecaterina” foster care center in Bucharest’s District 1, according to his adoption papers.

Nicolae remembers a room full of cribs, everybody crying, car horns from outside, sitting in a room forever, and nobody coming to the room.

He wrote a book about his early years called “Memories of Childhood: Life in the Romanian Orphanages”. The book has a small poem as a dedication.

“These Memoirs are dedicated to

My biological and adoptive mothers,

So that you will know a part

Of my life that you never experienced with me.”

Nicolae now lives in Berlin, where he’s enrolled in a master’s program at the Institute for Cultural Diplomacy. He hasn’t yet visited Romania, but when he comes to Bucharest, he first wants to visit the “Sfanta Ecaterina” foster care center. The center no longer exists; instead, it hosts the headquarters of the District 1’s General Directorate for Social Assistance and Child Protection.

The “Sfanta Ecaterina” foster care was closed before Romania joined the EU, as part of a large deinstitutionalization process. The institution was shut down and replaced with three alternative services, with pre-accessing EU funds of over EUR 1 million.

The orphanage was synonym to abuses, from getting whipped to being sexually abused by the other kids. Caretakers played a role, but it was a vicious circle, says Nicolae. Caretakers were cruel to kids, who became abusers. “The orphanage is viciously making people abuse others and themselves,” he adds.

When asked if it’s not too disturbing to talk about these things, Nicolae replies immediately:

“Not an issue. I think for me the abuse has been so much and I am so used to it that I’ve become detached from it,” Nicolae says.

Around 2000, a family of wealthy engineers from Missouri, US, started the process to adopt Nicolae, who was from a Roma family. Most of the people prefer to adopt babies, but this family wanted to give a chance to an older boy.

His adoption papers include a report drafted by the Sperante foundation, which describes Nicolae’s mental and emotional development.

"The language is normally developed, the vocabulary is well represented, he uses complex sentences and can reproduce short poems. (...) He is emotionally balanced and has a proper social behavior,” reads the report.

Nicolae was healthy and went to school. “For my parents, I was like the perfect kid. In the US they all think all these kids just need a loving home and they’ll be perfect. It’s a lot of myth and I guess good selling from the people at adoption agencies,” Nicolae says.

The adoption process took forever, but a final decision came in April 2002. The document certified that the adoption of Nicolae Viorel Burcea was carried out according to the law.

By June 2002, Nicolae had his first bedroom ever, in a white neighborhood in the Saint Louis area, in the Missouri state. He was eight and a half.

“For me, when I was adopted was like the best moment. Because I was like the most important guy. You come from a place where you are nobody and suddenly you are the most important person in that family,” says Nicolae.

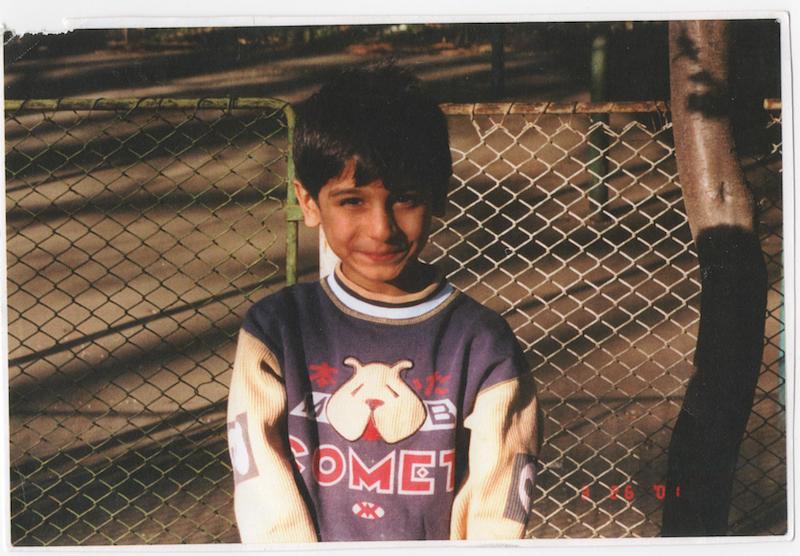

Nicolae in Romania

Nicolae in Romania***

His adoptive family was a very caring and loving one, especially his dad. His mom used to dream about adopting a kid since she was a little girl.

“I had everything,” says Nicolae.

It seemed like a fairy tale, but things didn’t go as planned.

Nicolae was not easy to handle. In school, he got suspended many times. He was aggressive, talking back to teachers, showing high defiance, not following orders. He once punched a disabled guy when the boy took his soccer ball and refused to give it back to him.

School was tough.

“People look at you and you have dark skin and your parents are white skin. How did this happen? This obviously makes you feel pretty awkward. Especially because I went to very white communities,” Nicolae says.

He’d have to explain that he had been in an orphanage. People would sympathize with it. But to him this was bad.

“Nobody gives me anything because I deserve or because I earn it. They always give it to me because they sympathize and this makes you feel less of a human when you are being victimized not by yourself but by all the people who are surrounding you,” Nicolae explains.

The boy suffered from reactive attachment disorder, a very rare disorder in which kids don’t establish healthy attachments with parents.

“Parents didn’t treat their kids right, didn’t love them and eventually you get people who are incapable of loving others. And when people show love, it’s seen as a threat,” Nicolae says.

He found it difficult to adapt to an organized, rule-driven family, after years of chaos in orphanages. The rules felt as authority, and he had been traumatized by abusive authority in his past.

“I felt that my power was being taken away from me. When somebody said 'go to bed at this hour', I was like: I don’t want to do that. The authority felt very much like the orphanage in that sense.”

His parents became obsessed with fixing him, took him to several therapists, put him on medication. The situation at home got pretty bad. Nicolae felt that he was cast in the troublemaker role and that no matter what he’d do, he’d be different from the rest of the family.

“I became this super obscene, super trouble kid who cannot work in this very nice loving family,” Nicolae says.

Nicolae tells the story as if he was the bad character who failed. This tendency stems from his first years in the foster care system, he explains.

“You are kind of taught to take the blame when you are in foster care. Why are you there? Why would a normal family put you there?”.

But things were more complex. His family had the money, the lifestyle, but they had no patience, they had no time, they were stubborn, very engineer- minded, Nicolae adds.

All the therapists would tell them to stop thinking of a kid as something that you could fix. “This is a kid who has been through a lot, is working through a lot. You can’t compare him to his brothers.” Nicolae remembers that his parents would lock him in his room for hours, for days.

He thinks that his parents were people who had never experienced big trauma in their lives, who wanted to help but weren’t prepared to deal with a traumatized kid, who was far from perfect.

Every night he would always ask them “Even if I’m a terrible kid would you give up someone like me?” That became a ritual, something he would do every night. And every night the parents would say “We love you till everything, never will we give you up.”

The constant fear that he could be abandoned again was there all the time.

***

Dealing with Nicolae created a rift in the family. His grandparents had one way of thinking how to take care of the kids and his mom had another. Nicolae remembers a summer trip to Florida when he was 12.

They got into a fight over Nicolae. His grandparents told the parents that Nicolae was just a kid, that he just wanted to go to the beach and have fun. “Leave him be. You don’t have to be so restrictive, always think that he’s no good. He may be, but not all the time. Kids are kids,” Nicolae remembers his grandparents saying.

Things continued to escalate. At 16, there was an incident when Nicolae became physical with his parents and he had a fight with his dad.

“My dad told me something and it came to me as very aggressive, at least verbally and I immediately stroke back. This was after the situation at home got really bad,” he says.

His parents called the police. The officer took Nicolae to a medical center, which is what happens if you don’t know where to put kids and you don’t want to put them in jail, Nicolae explains. After a few days, his parents had to pick him up.

They came to the medical center, only to drop him off in an institution two hours later. They went to the court a few weeks later and gave Nicolae up to the state.

“I think it’s a fairytale gone wrong for them. I think it’s literally a German fairy tale on a grim side,” Nicolae explains. “They never got what they wanted. They wanted a kid who loved them, followed their rules, a kid they could react to. I wasn’t that way.”

Then he adds: “This is just what happens. This is just the dark side of adoptions gone wrong.”

***

Nicolae now lives in Berlin, but spends the summer in London. People have often told him while he was abroad: “Oh my God, you come from America; please tell me how awesome it is. How great it is.”

Not only that he got the bad end of America in sense of family, but he also got the worst of it in the sense of where unwanted kids go, Nicolae says.

At 16, Nicolae became one of the United States of America’s unwanted kids.

In 2015, there were about 428,000 kids in the US foster care system, according to US official statistics.

“You get the kids who are unwanted and you get the kids who are high abusers. (...) Their lives are ruined. There is no other way of saying it. Many kids, two-thirds of us, would end up in jail. That’s what we were told. It was just a fact of life,” Nicolae says.

When he entered the foster care system, he went from being a terrible kid to a great kid. He had more freedom, he could dictate his plan based on his behavior. This was in the beginning. After some months, he became really frustrated about the system’s immovability. The education was terrible, nobody cared about you. He was scared to remain in the same institution for years, so he tried to force the system. The only way to move forward was to get expelled.

Nicolae moved to several schools and different levels of the foster care system. Meanwhile, his former adoptive parents were still in touch with him, although they were no longer his parents. This felt like a pressure for Nicolae. Once they relaxed their grip on him, Nicolae started improving. He decided to prepare himself for college. He read everything that he could find, wrote a lot.

At 21, the state gave him up, and his grandparents stepped more into the picture. They helped him pay for the college.

“We’ve always thought that he was very smart and he’s always wanted to go to college very badly so we’ve helped him with finances although he got some grants,” says his grandmother Velma. “If it didn’t work out it didn’t work out, but at least we felt that he had a chance.”

Nicolae joined a fraternity, became the school vice president, played football, had two jobs. He managed to do four years of college in two years. Nicolae’s good results weren’t a surprise for his grandparents.

“We were expecting that because he would read anything he could get his hands on,” says Velma.

“He knew a lot more about the US Government than I did,” adds his grandfather Marion.

After college, Nicolae came to Europe, where he’s currently in a master’s program in international relations.

One of his teachers recently asked him if he felt that he belonged anywhere. He doesn’t feel American, nor Romanian, but he’d like to come to Romania someday and do something big here; maybe even run for the president office someday. Many people have told him that it’s a crazy dream, but Nicolae says that he doesn’t want a simple life. He wants to inspire people, to change Romania’s image abroad.

“I would say my parents never left me so much room to kind of do things on my own. They thought I was a kid, treated me as a kid, never let me do things independently. This caused a rift in the family. It just became a psychological battle between me and them. When I had the freedom to do what I could do, all I had to do was show people: look, I am an exceptional kid.”

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com