Opinion: The unemployed generation in Romania – reality check

There are increasing talks about the rise of a "lost generation". After the generation of sacrifice, referring to those who struggled with the transition from communist values to market economy, "the lost generation" refers to the young generation who cannot find a job due to the crisis and economic uncertainty in the past 5 years.

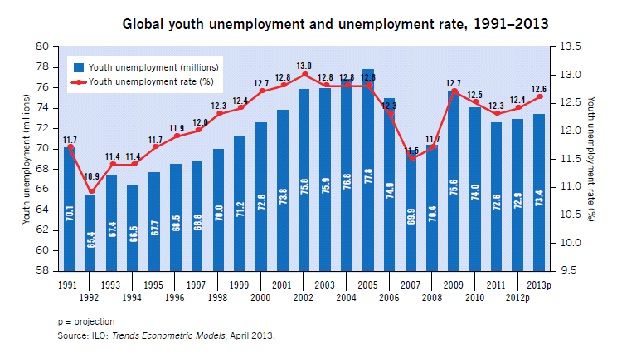

Only, this time around, Romanians are following the trend. The phrase referring to Romanian youths as a "lost generation" is used in the reports of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and other studies that deal with world-wide unemployment and labor. The global youth unemployment rate (aged 15 to 24) is estimated by ILO to 12.6 percent in 2013 (in the Global Employment Trends for Youth 2013 study), close to that recorded during the peak of the crisis, that is 12.7 percent in 2009. In absolute values, this percentage means 73.4 million young people, and the trend is going up. By 2018, the youth unemployment rate is estimated to increase to 12.8 percent, while the ratio of youth to adult unemployment rates will remain within the levels from the past few years, namely 2.7. This means it is almost 3 times more likely for a young person to be unemployed than for an adult.

Though it may perhaps seem paradoxical, the most affected countries are those with developed economies and the EU, close in statistics to Middle East and North Africa. In these regions, youth unemployment has continued to rise since 2008, while, in developed economies and the EU, the rate increased even by 24.9 percent between 2008-2012.

Meanwhile, there is much talk about discrepancy between the skills of those looking for a job and the knowledge and skills required by employers. And the gap is widening. But there is also good news: in Romania, the same study of ILO from 2013 states that this discrepancy decreased by 3.5 percentage points between 2010-2011, from 12 percent to 8.5 percent, being the largest decline among the analyzed countries, after Estonia and Greece.

The lack of skills coexists with a contradictory fact: overqualified young candidates. According to the same study, 15 percent of Romanian young people are "too" educated compared to market demand. And this rate is higher in Romania than in Britain and Germany.

Also referring to education, unemployment among youths having graduated from tertiary education institutions (technical schools and universities) is very high in Romania, reaching 29.3 percent in 2011, with a rise compared to 2010 and more than triple the level registered in 2000.

All these persistent difficulties, along with the slowing global economic recovery in 2012 and 2013, led to indifference and pessimism. Increasingly more young people gave up searching for a job, and many are satisfied with jobs that are below their qualifications.

Certainly, reversing this trend in the unemployment rate among young people and bringing back optimism in their professional future is a very expensive process. It requires visionary public policies. But the alternative of not acting upon this is at least as expensive, with obvious social and economic costs: lower savings and lower consumer demand as young people are supported by their families, with smaller amounts for investment remaining in the household, but also on the long term when, even if employed, they will reach a maximum salary level below the one of the previous generation.

There are also political costs, given that youths with lack of perspective have a high level of Euroskepticism.

One of the most valuable solutions, although not that obvious for some, for reversing youth unemployment is to support entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship comes with two sources for decreasing unemployment: the more companies are set up, the more will the number of employees increase; and the more young people become entrepreneurs and become self-sustained, the more will the number of unemployed people decrease. According to the EIM Do SMEs create more and better jobs? report, employees of SMEs (with less than 250 employees) are, on average, two thirds of the number of employees in the G20 countries. These companies create jobs at twice the rate of very large companies and are more willing to hire unemployed people.

But in order to increase the number of entrepreneurs, funding and mentoring is needed, two lines of action that are imperative to supporting their activity (according to the EY study EY Avoiding a lost generation, which surveyed 1,500 entrepreneurs from G20 countries, of which 1,000 did not turn 40). Funding without mentoring is inefficient, as well as mentoring without funding. Overall, 88 percent of entrepreneurs who have experienced business leaders as mentors survive on the market. The need for some kind of support mechanisms is very high, especially for young entrepreneurs, who are just starting out.

Equally important, bureaucracy, a topic as often discussed when considering supporting start-ups and entrepreneurs as the issue of funding, needs to be reduced. To succeed, young entrepreneurs need a more simple and friendly environment in terms of tax and regulations. More than 53 percent of entrepreneurs surveyed by EY believe that this simplification would crucially support their entrepreneurial efforts. Most young entrepreneurs are frustrated by the regulatory and fiscal environment, at the moment generally designed to serve larger companies.

Therefore, young people and entrepreneurs need to be considered together when looking at the opportunity to support either of these categories. In this manner, support becomes a win-win situation for young people and entrepreneurship alike.

By Mihaela Matei, guest writer

Mihaela Matei is Marketing Supervising Associate EY Romania, coordinator of the EY study Entrepreneurs Speak Out.