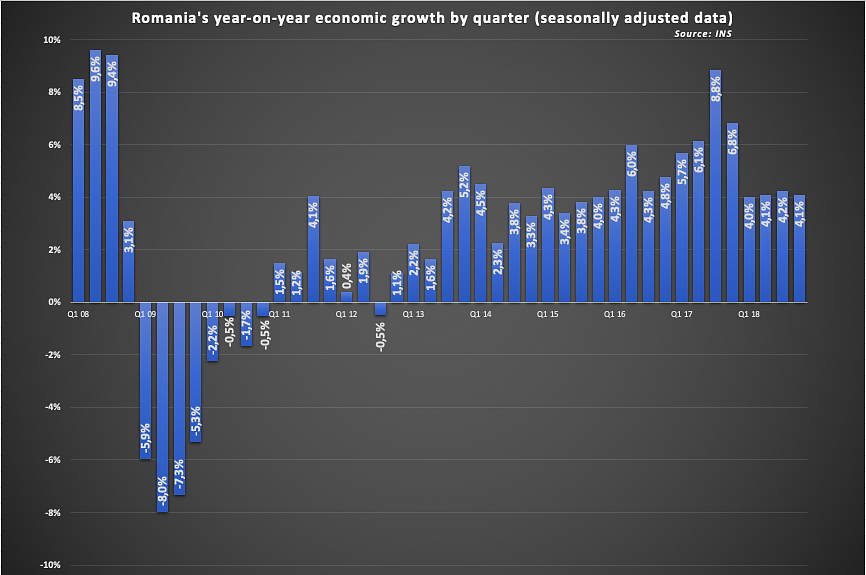

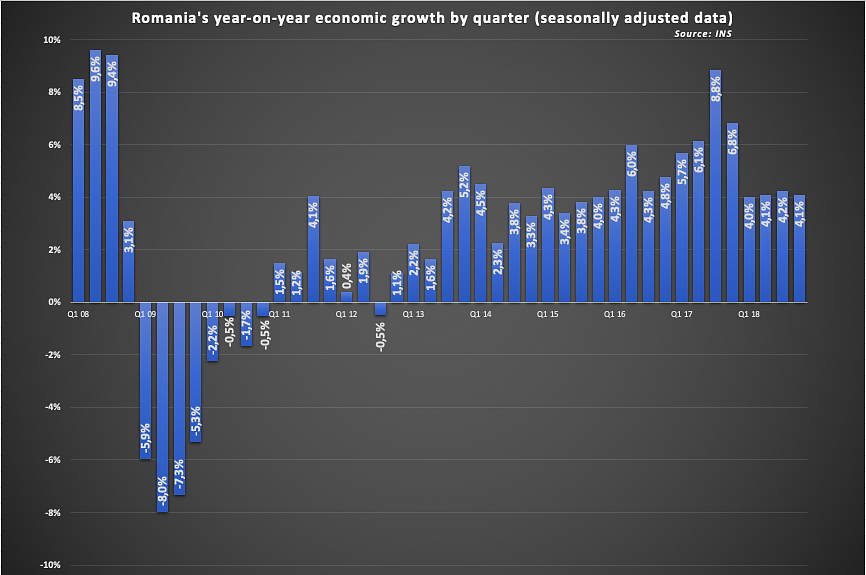

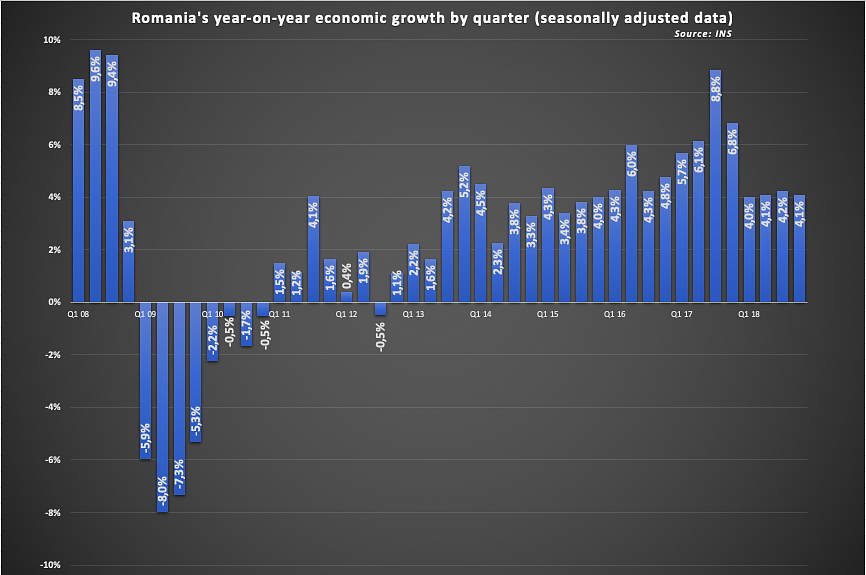

Chart of the week: Romania’s economic growth, slower but stable in 2018

Romania's GDP increased by 4.1% year-on-year in the last quarter (Q4) of 2018. The flash estimate prompted positive surprise since the country's economy is expected to enter the slowdown stage of the economic cycle.

Declining consumer confidence supported such expectations but the retail sales remained strong (+5.9% year-on-year) amid sharp rise in wages (+8.1% year-on-year, in CPI-deflated terms) and outstanding consumer lending (+28% year-on year, CPI-deflated terms as well). The final consumption eventually rose by 5.9% year-on-year, more than the 4.9% average growth in 2018.

But the strong domestic demand pushed up the imports to the point that the net imports accounted for 4.6% of the domestic demand, the highest value since 2012. The continued robust growth has also been supported by further accumulation of inventory: without the contribution of inventory piling up, the growth would have been only 1.5% in Q4 and below 1% in each of the previous two quarters. The sluggish exports might be at the root of the continuing rise in inventory. Thus, the exports advanced by only 1.6% year-on-year in Q4, versus 4.6% average advance in 2018.

The case for wage-led-growth

A country's GDP is the best macroeconomic indicator to capture the dynamics or the size of its economy by measuring the wealth created over a given period (a year or a quarter). On the long term, this wealth accumulates (as gross fix capital formation or inventory) or is consumed by households, government or other non-government organizations.

Debatable in theory but frequently in practice, the GDP growth is used to measure the success or efficiency of a government's policies. A way of looking to the GDP is by the breakdown into wage share (or labor share) and the profit share (or capital share). Shifting the wage share toward higher values increases households' wealth, but this is not possible indefinitely and can be done mainly when the wage share is below global or region's average.

Romania's ruling coalition led by the Social Democratic Party (PSD) pursues a wage-led-growth by pushing up the wages (hence the wage share). Beside having among the lowest incomes, Romania features one of the wider disparities as well (unequal distribution of GDP -- or wealth, among people). This might support wage-led-growth policies as well. While statistics indicate that the wage share in Romania is below the EU average, meaning such policies make sense, maintaining sustainable growth is another requirement to observe. Therefore, if they are to succeed, such policies need a second leg -- namely policies aimed at helping the private sector increase profitability in line with the wages: predictable regulations primarily, but also public infrastructure (transport, education, research, health care).

In the absence of such a growth-friendly environment (which tends to be the case in Romania), the first leg, pushing up the wages will likely result in limited economic development around "pockets of wealth" (be them defined in terms of geography or industry) along with continuing migration of workforce and population.

Romania's economy expanded by one quarter in the past five years

Romania's GDP -- which is a measure of a national economy's output, has increased at a real average annual rate of 4.6% over the past five years, driven by rising households' incomes, low interest rates, and robust external demand, accumulating an impressive 25% advance in 2013-2018. Compared to the peak level reached in 2008, before the recession, Romania's GDP was in 2018 nearly 23% higher than it was ten years before. Its sustainability, measured by the Current Account balance and price stability, is more robust than it was in 2008, despite risks posed by the excessive fiscal stimuli, lack of regulatory predictability and higher interest rates.

Over the past four quarters, the annual GDP growth has hovered around 4% -- which is a healthy rate in absolute terms. But signs of weakening surfaced: the robust demand for consumption prompted rising net imports and to a lesser extent domestic production; separately, the inventory (possibly absorbing part of the domestic output) keeps piling up.

The limitations of the wage-led-growth model advocated by the incumbent Social Democrats might become visible (or not) this year, when the government expects (or plans, given its more direct involvement in the economy) 5.5% GDP growth, nearly double the consensus forecast. Weaker external demand and the lack of investments in infrastructure, regulatory predictability and decent absorption of cohesion funds are behind the bleak expectations.

On the upside, the private sector still demonstrates optimism: companies are investing in technology to cope with the tight labor market, and the real estate keeps growing particularly in first-tier cities. The primary challenge for growth remains the normalization of the economic policies, which turned particularly volatile in early 2019 and risk remaining unpredictable amid European, Presidential, local and general elections within less than two years.

2019 will test the wage-led-growth model pursued by authorities

For 2019, the European Commission forecasted for Romania 3.8% growth, under the Winter Forecast, while analysts are even more cautious: Romania's leading bank Banca Transilvania said in January it expected 2.8% growth, grounded on the weaker dynamics of the euro area (Romania's main economic partner) and adjustments in internal economic policies after the robust fiscal stimulus of recent years.

Last year's performance was lower than the initial expectations of officials and even local analysts. In February 2018, the Government was envisaging 6.1% GDP growth for the full year. As the performance fell below expectations, it gradually reduced the forecast to 4.5% in November. Compared to the 6.1% February 2018 official forecast, both the domestic and external demand were weaker. Thus, the final consumption actually increased by 4.9% compared to 6.3% projected.

Gross fix capital formation contracted by 3.2%, while the government expected a robust 7.9% increase. The exports also increased by only 4.5% compared to 7.5% projected. Imports, in contrast, grew in line with projections, by 8.6%. Given the domestic demand for both consumption and investments, weaker compared to the February 2018 official forecast (6.1% GDP growth), imports advancing at forecast level is a negative performance for local producers, who keep losing ground in front of imported goods.

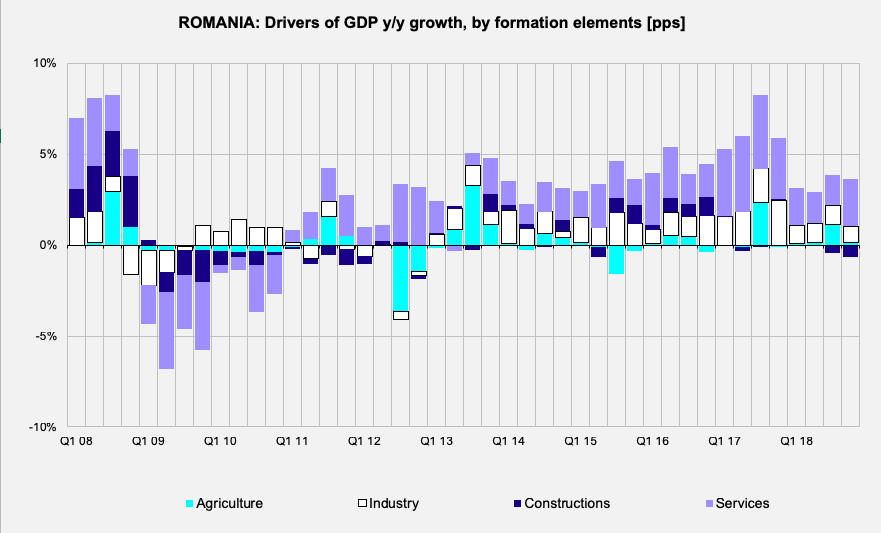

Unboxing the GDP: Production side

One of the three main GDP breakdown options is by the main economic sectors that generate value added. Given its high share in total value added generated (some one third in 2018, including Information and technology, Banking and Real Estate), the sector of Services makes the stronger contribution to the overall growth as well. But the value added reported by the sector tends to increase disproportionately when demand rises sharply as well, giving the service companies the opportunity to increase their profit margins (in the context of imperfect competition).

Industry, which represents about one-quarter of the gross value added generated by Romania's economy, has made a constantly significant contribution (some 1 percentage point) to the overall growth. Notably, the sector of constructions despite its rather moderate share in total value added made a significant negative contribution to the GDP growth: -0.3pp. The negative performance was -0.64pp in Q4.

On the production side in full 2018, industry (23.7% of GDP) contributed 1pp to the entire year's growth rate, while the sector of services to households (18.3% of GDP) added another 0.7pp. The Information and Technology sector, despite its still low share in total GDP (5.2%) made an impressive 0.4pp contribution to the overall growth thanks to robust 7.0% advance of the value added generated.

Unboxing the GDP: Utilisation side

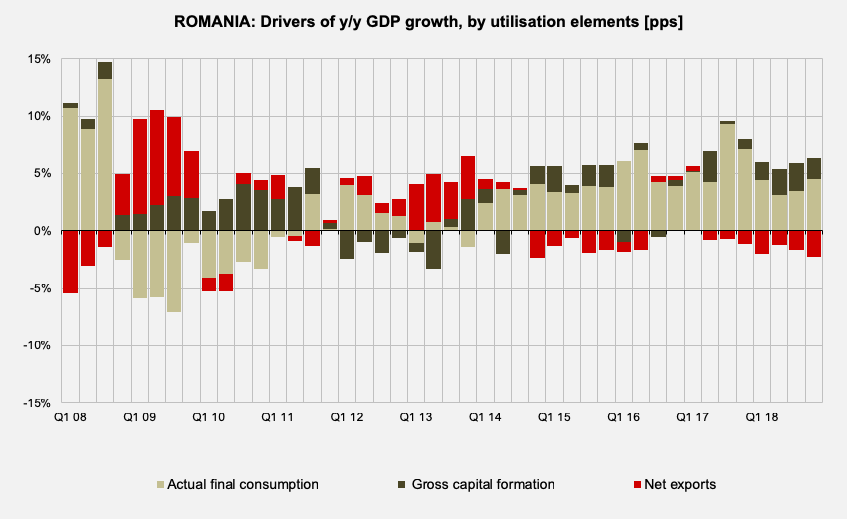

Another popular GDP breakdown is by utilization: for consumption, investments, and export. In the case of Romania, the net export is negative, meaning the country used part of the resources from import.

Internal consumption contributed 3.9pp to the GDP growth in the year, mainly driven by the households' direct consumption (3.3pp contribution). The gross fix capital formation made a negative contribution (-0.7pp) despite the significant inventory build-up that had a robust 2.7pp contribution to the GDP growth in 2018. In other words, 2.8pp of the 4.1% GDP growth in 2018 came from the increase in inventory (as opposed to consumption, investments or exports). The gross fix capital formation (the increase in productive capacities) was 3.2% lower, at comparable prices, than in 2017. The inventory cycle was not showing signs of reversal in Q4, when the contribution of the inventory build-up was 2.6pp to the 4.1% year-on-year growth.

When it comes to the external sector, exports increased by 4.7% year-on-year in 2018 (comparable prices) while imports soared by 8.6% year-on-year.

By Iulian Ernst, Editor Romania-Insider.com; iulian.ernst@romania-insider.com