What does home now mean for the Romanian diaspora?

More than three million Romanians left the country to work abroad between 2000 and 2015, according to a UN report from 2015. The Romanian diaspora grew by 7.3% a year during this period. After Syria, it was the second fastest annual growth rate in the world. This migration abroad is one of the most important trends shaping modern Romania, and yet little things are known about it. A scientific project of the Autonomous University of Barcelona called Orbits tries to fill in the the gaps by looking at the Romanian diaspora in Spain.

The St. Elizabeth Chappell stands right next to the Faculty of Sociology and the Faculty of Psychology in Bucharest. It is a bit ironical given that these are secular topics, says Gabriel Marian Hâncean, an Associate Professor at the Sociology Department of the University of Bucharest. But it’s a very old church, he adds.

The Romanian is part of the Orbits team, led by the professors Miranda Jessica Lubbers and José Luis Molina of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). Southeast Europe and Romania in particular are Molina’s main areas of interest.

I contacted proffesor Hâncean after I read about Orbits, a project looking at the Romanian enclaves in Castellón de la Plana, on the eastern coast of Spain, and Roquetas de Mar, in the south of the country.

Even if local politicians talk about the need for Romanians to return to their home country as Romania faces labor shortage, and almost everybody I know has friends or relatives working abroad, there is almost no serious talk about immigration in the public space. We know close to zero about the millions of people who left Romania driven by the desire to have a better life.

The Orbits project is financed by the Spanish government through the Economy, Industry and Competitiveness Minister. So the Spanish government, and not the Romanian one, is paying to understand the Romanian diaspora.

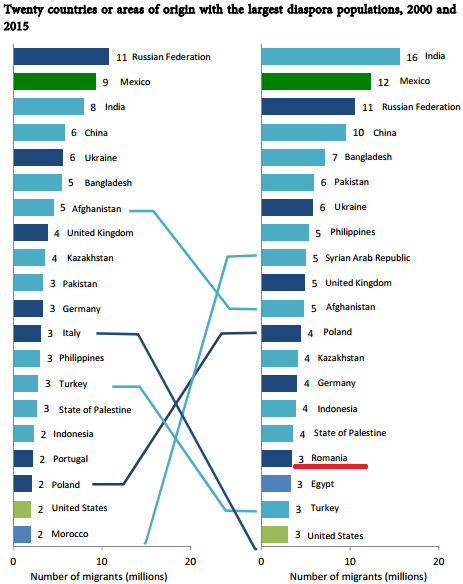

International Migration Report 2015 - the United Nations

International Migration Report 2015 - the United NationsWhen we meet, Gabriel Hâncean, a man in his mid ‘30s specializing in social network analysis, shows me the website of the European Commission and that of Horizon 2020, the biggest EU Research and Innovation programme ever, with funds of almost EUR 80 billion.

Migration is one of the European Commission's ten priorities. The Horizon 2020 programme has funds aimed at understand migration.

Hâncean then opens the document presenting Romania’s development and innovation strategy for the 2014-2020 period. Bio-economy, space and security, energy, climate change are included among priorities. Migration is not even mentioned once.

“What does the Romanian state do for the citizens who leave the country, what does it do for them to return? These are rhetorical questions. I haven’t seen anything, no initiative,” Hâncean says.

***

The Romanian diaspora is organized unevenly. Romanians haven’t migrated to the whole Europe, but to specific countries. They represent the largest European minority in Spain and Italy. The same global pattern is reproduced in Spain, for example. Romanians didn’t settle in the whole country, but in specific areas, in the so-called demographic enclaves.

This is where the questions start, Hâncean says.

Why are they there? Are these enclaves volatile? Where do these people come from? Is the community stable? Did Romanians manage to integrate? What is their story?

Castellón de la Plana, for example, has over 17,000 Romanians out of a total population of 170,000 people. Most of them are from Targoviste, a small town in Southern Romania.

The Orbits project aims to understand this community by using the social network analysis. How does migration takes place? How do people migrate?

The project began in 2016, but field research officially started in November this year. The research team will apply 600 questionnaires, 150 each in Targoviste and Bistrita in Romania, and Castellon and Roquetas in Spain. The team will also do 200 in-depth interviews. The Targoviste-Castellon areas will be the main focus in the beginning. The first results should be published end- April 2018. Next summer, the second stage of the project will kick off, focusing on the Bistrita-Roquetas areas.

Gabriel Hâncean and José Luis Molina

Gabriel Hâncean and José Luis MolinaA network is composed of nodes and links. The nodes are people and the links can be friendship relationships, explains Gabriel Hâncean, while drawing a network in his Bucharest office.

Cristina is friends with Daniela, who is friends with Elena. They all live in Targoviste. Cristina leaves Romania and moves to Spain. She’s part of the first wave of migration, the so-called pioneers, who left on their own. She settles in Castellón de la Plana, but she continues communicating with Daniela, who still lives in Targoviste, by using the phone, Facebook, whatsapp or skype. Daniela listen to stories about Spain and starts thinking about moving there as well. When she finally decides to leave Romania, she will also move to Castellon, because her friend Cristina is already there. Transnational connections are thus born.

“If you look on a map, you see countries. But if you ignore the countries, you see people flows (...) links that connect various places in the world and which are built by these migrants,” Hâncean says.

“If you look on a map, you see countries. But if you ignore the countries, you see people flows (...) links that connect various places in the world and which are built by these migrants,” Hâncean says.

Organizations soon form, which support these flows of people. Telecom companies, offering advantageous mobile packages, transport companies, churches, planes, will become part of this infrastructure.

“You can replace Romanians with other people and you’ll have the same transnational circulation,” Hâncean explains. “This is actually the new reality in which we live.”

This social reality is different from the reality we know, with countries, borders and passports.

“I wonder what does the idea of origins now mean. What does it mean that someone is from that a place when we have all these flows,” the Romanian researcher says.

Before kicking off the Orbits project several weeks ago, the Spanish team did an ethnographic research in Castellon for one year. They spent time with Romanian people, went to their homes, talked about their plans. They learned that the probability to return “home” is very low. The idea of home is quite relative.

During the economic crisis, which hit Spain very hard, Romanians in Castellon didn’t return to the small Romanian city of Targoviste. Some of them went to other countries in the EU following different migration routes, while some remained in Spain. When the effects of the economic crisis started to fade away, Romanians returned to Castellon, not to their country of origin. They defined a new origin in Castellon. The team will look into how this identity is born and shaped in the diaspora.

When the Orbits project was launched Spain, Gabriel Hâncean met with Romanian students who were born in Spain.

“It’s very interesting to analyse how they understand the idea of being Romanian, given the fact that they were born there,” the Romanian researcher says.

What does it mean to return home? The question gets a whole new meaning.

“I think the question is about an old reality,” Hâncean says.

Politicians seems to visualise Romanian immigrants as people living in transit, people who are ready to come back at one clap.

Romanian labor minister Lia Olguta Vasilescu recently said that Romania is facing a very high labor shortage in sectors such as IT, health, constructions or agriculture, and Romanians who work abroad need to be drawn back.

Officials tend to ignore that the people who left the country have defined new realities. Some bought apartments, they’ve started families, made new friends. Politicians also ignore that most people left Romania because they were struggling in this country and wanted a better life.

Bringing them back after 15 years could simply be too late.

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com