Romanian film review – Unmissable: Uppercase Print

Having just screened at the prestigious Berlin International Film Festival, one of Radu Jude’s two current films, Tipografic majuscul/Uppercase Print, was released in Romania two weeks ago. It should not be missed for the simple reason that it is a Jude film, but even more so due to its theme and approach. The director’s more recent titles are all particularly urgent in terms of content, while also being more daring and assured formally.

Starting with his drama Aferim!, a period piece set in 19th century Wallahia when Roma people were kept as slaves, and continuing with Țara moartă/The Dead Nation (2017) and Îmi este indiferent dacă în istorie vom intra ca barbari/I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians (2018), focusing on Romania’s antisemitic past and its reluctance to address it, Jude has been the most consistently outspoken director on such thorny topics.

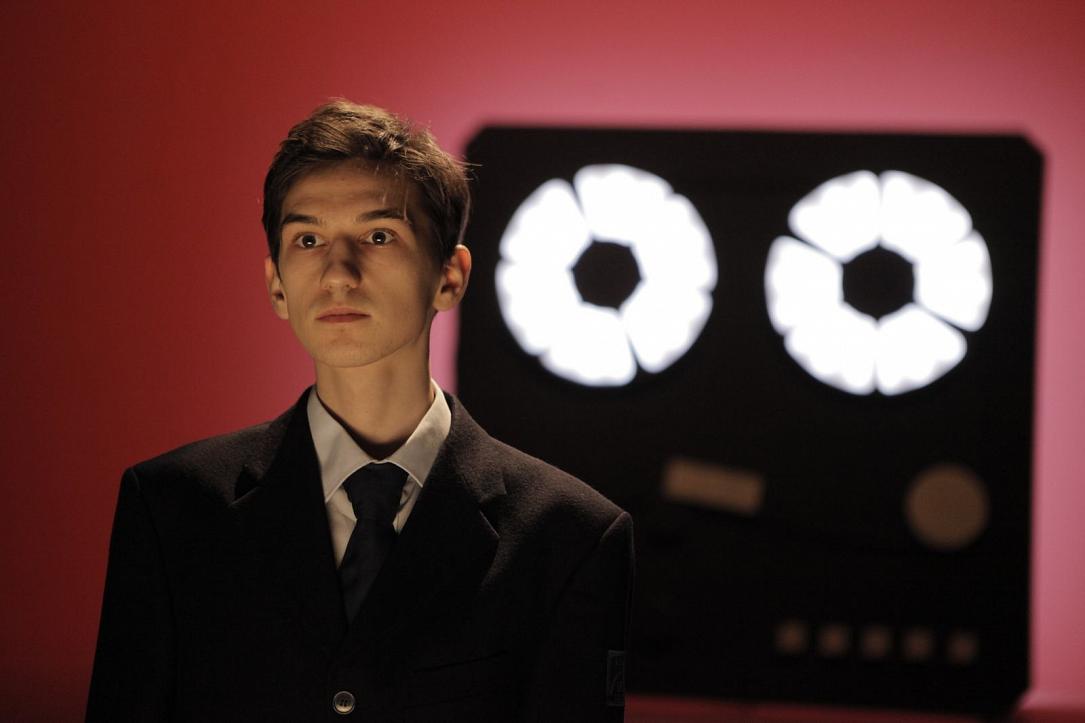

Uppercase Print is just as sharp and quietly devastating as the aforementioned works, although more tonally restrained. Working with excellent theatre director Gianina Cărbunariu by adapting her eponymous 2013 “documentary play”, the film tells the real story of 17-year-old Mugur Călinescu who in 1981 scribbled the walls of his native Botoșani in uppercase letters with slogans such as “We want food and freedom” or “We are sick of waiting in endless queues”. A Radio Free Europe fan, the rebellious teen was released after long interrogations by the secret state police, the feared Securitate, but eventually died in 1985 from leukemia. It was later assumed he had been irradiated by the Securitate over the years.

Călinescu’s story is told in static pieces, with the actors standing in fixed points, either facing each other or the camera, delivering their lines in a disaffected manner. The Brechtian approach defies expectations since the topic is such a dramatic one, but it also helps keep things cerebral and encourages a reflexive rather than an emotional reaction. These scenes are juxtaposed with a series of propaganda clips from the National Television archives showing the ’benefits’ of the socialist state in various areas of everyday life. As a fun bonus, the filmmakers included some particularly amusing ones such as catching honking drivers or finding inventive spaces for beating one's carpets (anyone who grew up in a social state understands the ubiquity of the first and the urgency of the latter). They are both a welcome respite from the declamatory, clinical theatre-based scenes, often acting as a (most probably unintended) comic relief, and a necessary counterpoint, showing the lies of a system that pretended to have its citizens' well-being at heart, but instead oppressed them and punished any form of resistance, as with Călinescu’s.

While undoubtedly more accessible than The Dead Nation or his other current film, Ieșirea trenurilor din gară/The Exit of the Trains, Uppercase Print is still demanding viewing, and its full impact unfolds after the screening. Jude and his ace editor Cătălin Cristuțiu connect the different material with utter precision, and their impressive wave of connections and allusions is best appreciated on repeated screenings. Nothing is shown or cut at random here, the film works like a perfectly wound mechanism. It demands absolute attention to detail and a fast grasp of what is seen. The Călinescu scenes are the most testing ones since they make no concession whatsoever to a more conventional approach to storytelling, which might make Uppercase Print ultimately easier to admire than to enjoy.

But this might be exactly what this type of film aims for, as this kind of story should stir more than entertain, and there is so very much to admire here, from the already mentioned formal perfection to the film’s many references (theatre, art, historiography) and not least its undeniable ethical and moral stance. It is wise enough to understand that collaborating with the system was sometimes a matter of context than of character (the Securitate was well-versed in recruiting children and youth as informers) while not excusing it, and it pays homage to forgotten heroes without putting them on a pedestal. But most of all, it is a virulent critique of a dehumanizing system and poses (uncomfortable) questions on its ramifications for the present.

Jude’s aforementioned The Exit of the Trains, also to be released domestically this year after its Berlinale premiere, is a much more oppressing experience, but it is unlikely you will see a better dissection of this country’s past and its connection to the now than in such necessary, formally arresting, painstakingly researched, but most of all earnest, uncompromising and (in the case of Exit) monumental documentaries. Watch them, their significance will gather momentum.

By Ioana Moldovan, columnist, ioana.moldovan@romania-insider.com

(Photo source: Cinemagia.ro)