Fingerprints of the Past: Cluj photographer tells the story of life as a wealthy peasant under Ceaușescu’s regime

Denisa Moldovan is a law student at Babes-Bolyai University. While pursuing journalism as her double degree, she dived into her roots in a new photo report, “Fingerprints of the Past.”

The project features pictures of her nostalgia trip to capture what was left of her family’s past. It initially started as a photojournalism workshop project for her teacher, Calin Ilea, at the College of Political, Administrative, and Communication Sciences at Babes-Bolyai University, but the more she dived into the story, the more she found interesting pieces of her upbringing.

“He was hesitant about the subject at first, because the focus is dead and you can’t really follow up anything, photo-wise, from a dead person,” she recalls, adding, “But I knew I could dig up documents and ask his surviving sons, and that’s how I started the story. I’m really proud that I could bring his story to life because it is a part of my history, on a smaller level, and our country, on a much wider level.”

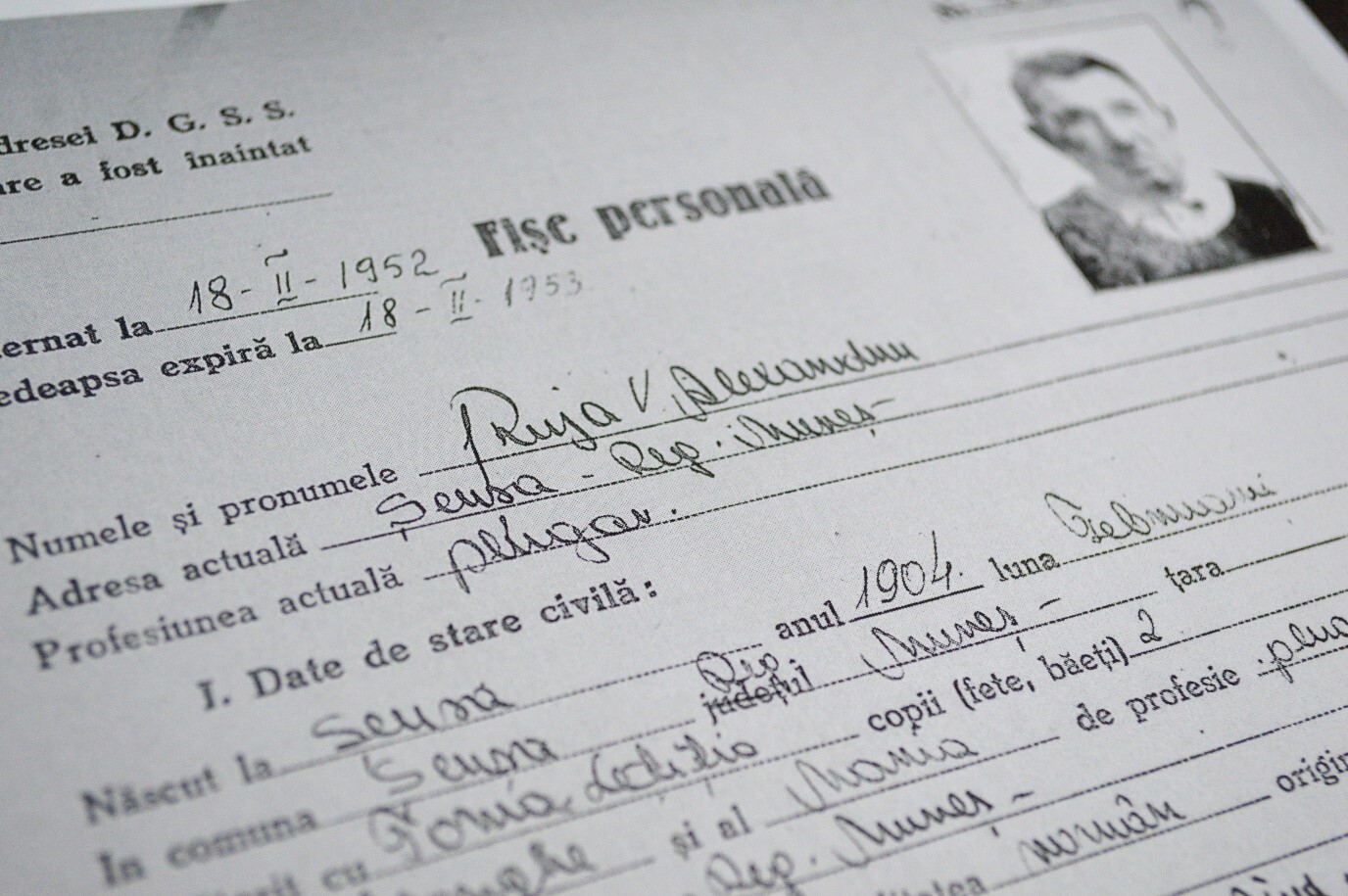

Photo 1: At the crossroads, in a small village called Șăușa, in Mureș County, Alexandru lived between 1904-1983. Born into an ordinary peasant family, a plowman by profession, he worked and made a fortune: 12 hectares and 10 acres, 4 working cattle, a 2-room house and a complete agricultural inventory.

Photo 2: In 1949, Alexandru was declared "cheabur" by the Romanian Communist Party. Inspired by the “kulak” notion, which was imposed in the Soviet Union back in the day, the term serves in a pejorative manner to frame prosperous farmers. During this time, the government would seize crops like wheat, corn, living stocks, or anything they could get their hands on from the rich. Not wanting to give it up, Ruja faced 12 months behind bars.

Photo 2: In 1949, Alexandru was declared "cheabur" by the Romanian Communist Party. Inspired by the “kulak” notion, which was imposed in the Soviet Union back in the day, the term serves in a pejorative manner to frame prosperous farmers. During this time, the government would seize crops like wheat, corn, living stocks, or anything they could get their hands on from the rich. Not wanting to give it up, Ruja faced 12 months behind bars.

The document reads, "The aforementioned is a dubious element towards our regime and all the decisions and directives given by the government he sought to give them a different course and a different interpretation.".

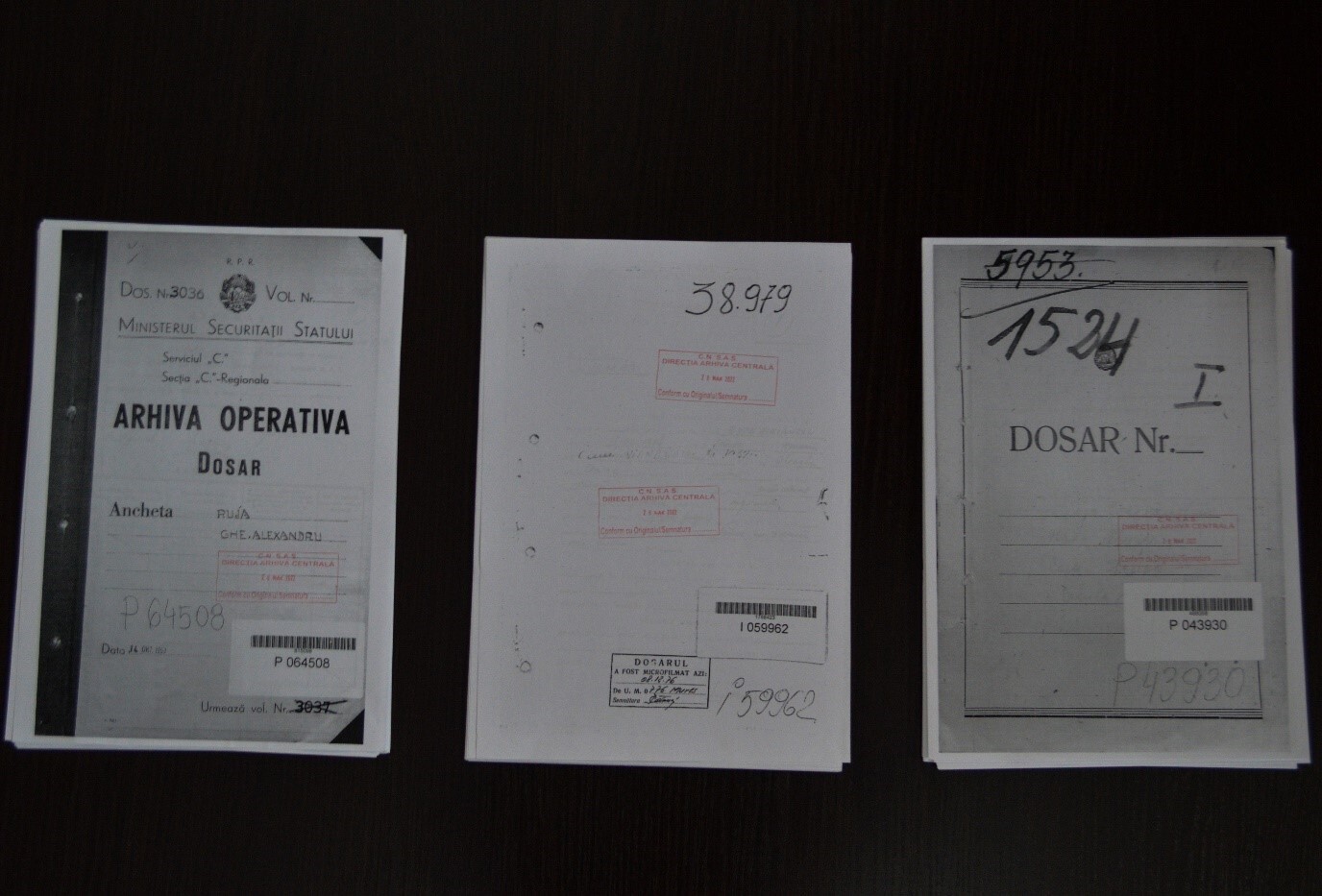

Photo 3: 3 files. The first, which contains 17 pages, was enough to sentence him to 12 months in prison. The second, 23 pages, and the third, 64 pages, documented information about him from his release until he died.

Photo 3: 3 files. The first, which contains 17 pages, was enough to sentence him to 12 months in prison. The second, 23 pages, and the third, 64 pages, documented information about him from his release until he died.

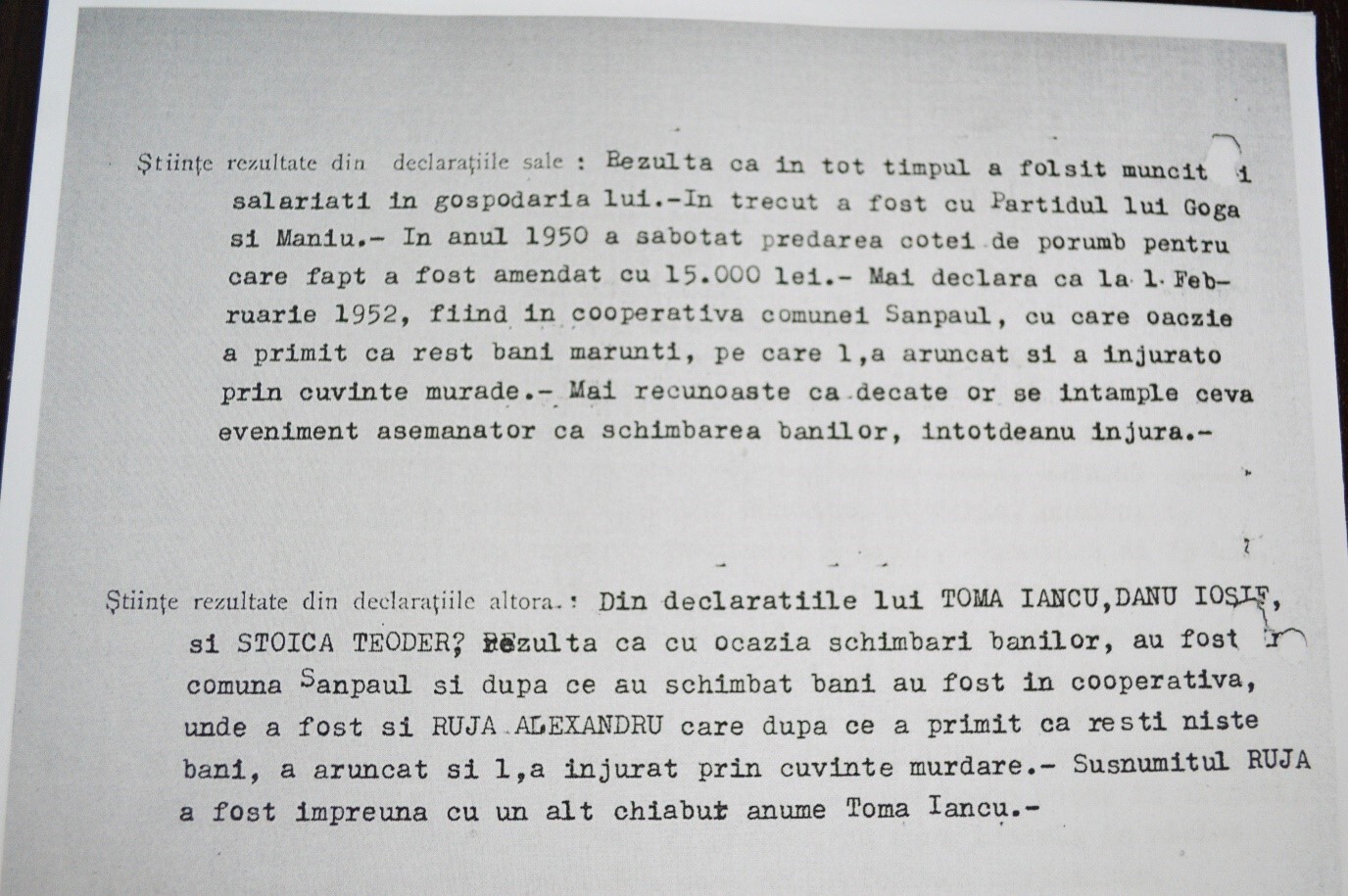

Photo 4: The investigation report contains the reason for being imprisoned. It reads, “A National Peasant Party sympathizer who refused to surrender corn quotas and boycotted the 1952 monetary reform.” The latter introduced the third leu, ROL, to the masses and lasted until 2005.

Photo 4: The investigation report contains the reason for being imprisoned. It reads, “A National Peasant Party sympathizer who refused to surrender corn quotas and boycotted the 1952 monetary reform.” The latter introduced the third leu, ROL, to the masses and lasted until 2005.

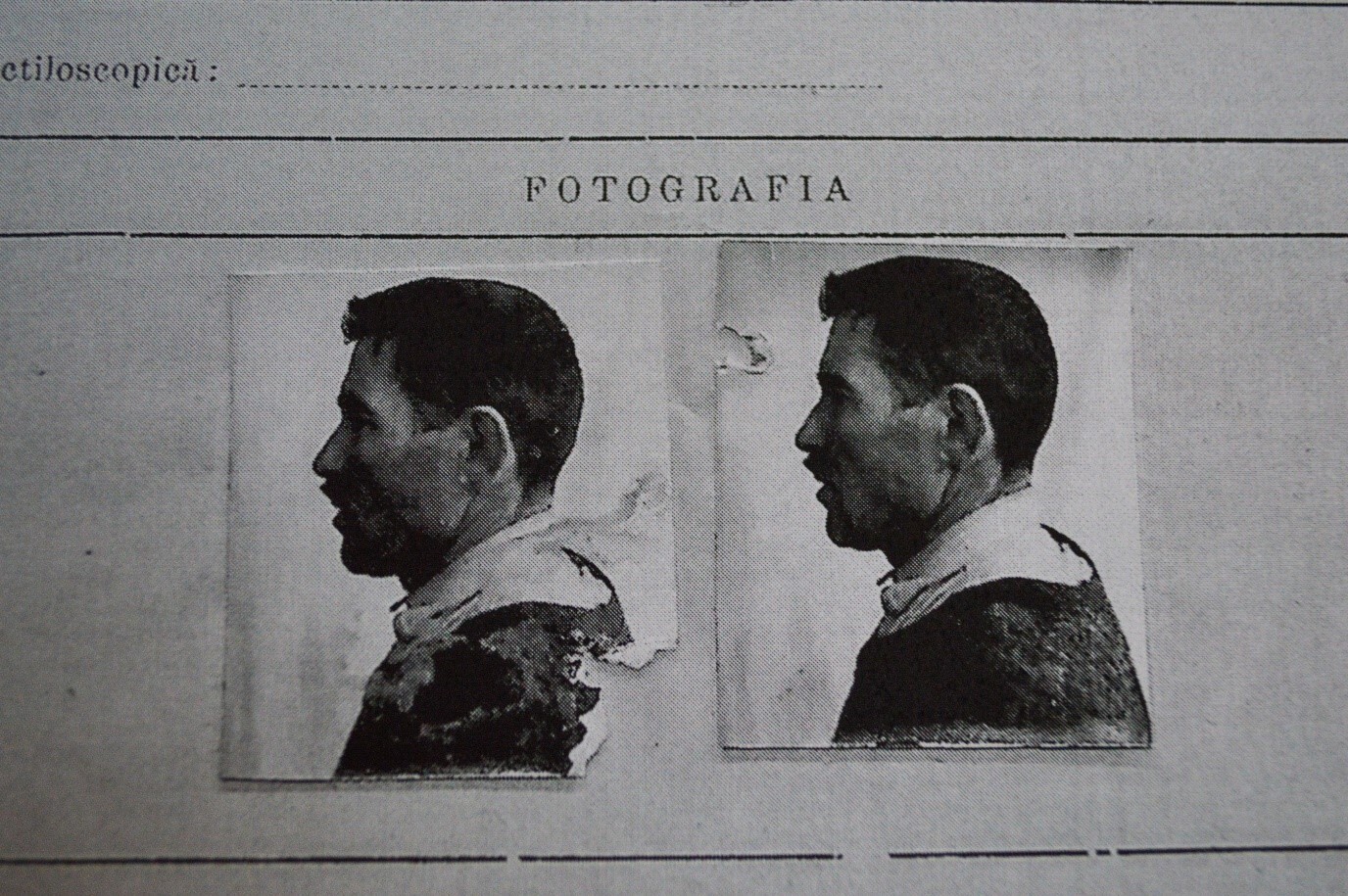

Photo 5: Mugshot. Alexandru passed away in 1983, but left behind 2 boys, Sandu (91) and Ion (82, the photographer’s grandfather). On his death certificate, his first name was changed to Sandor, a predominantly Hungarian name.

Photo 5: Mugshot. Alexandru passed away in 1983, but left behind 2 boys, Sandu (91) and Ion (82, the photographer’s grandfather). On his death certificate, his first name was changed to Sandor, a predominantly Hungarian name.

Both of them weren’t easy to talk to, suffering from old age and dementia. She eventually took a trip to the village where Sandu, the eldest, lived with his wife, Ana. The pair met when they were 15 and have been together since.

Photo 6: Alexandru’s tombstone with 2 ears of corn.

Photo 6: Alexandru’s tombstone with 2 ears of corn.

Photo 7: Family photos with Sandu (right, b. 1931, 91 years old) and Ana (left), his wife. She told us the story of how the government took Alexandru in 1952, where then he would be forced to work at the Danube-Black Sea Canal, one of the bloodiest construction sites in the history of the country, and excavate the navigable canal among 20.000 other detainees, mostly political prisoners.

Photo 7: Family photos with Sandu (right, b. 1931, 91 years old) and Ana (left), his wife. She told us the story of how the government took Alexandru in 1952, where then he would be forced to work at the Danube-Black Sea Canal, one of the bloodiest construction sites in the history of the country, and excavate the navigable canal among 20.000 other detainees, mostly political prisoners.

"They took him from home and took him to the canal. It was winter when they took him. There was a lot of snow. They put handcuffs on his hands and made him go ahead of them to make way for them. And it snowed, and it snowed, and there was a big snowdrift.”

“They arrived at Mureș, and it was turbulent water, and there was no bridge, there was only a boat. And the ferryman asked them, “Why don't you take the handcuffs off this man? Yes, if we all go by boat, he cannot save himself.” And they passed by Mureș, but they still kept it in front of them. With his back to them, he could only think of the sound of the bullet shooting him.”

“He was put in a van next to 4 others and went to the city. There they investigated him, but my father-in-law was never the mayor. They were only doing that to put him in prison.”

“He didn’t recognize nothing. He said they took him to the office, and they took a wooden suction cup and broke his tooth. After that, he was put in the ice prison. There were 4 walls of ice and that was all there was as far as the man entered, and the water flowed underneath. They kept telling him “admit it, old man, if not you’re going to freeze here,” but he didn't admit it, and that's how his feet froze.”

Photo 8: The pigeon houses. Alexandru would keep the corn quotas that he refused to hand over in 1951 here, a year leading up to his arrest.

Photo 8: The pigeon houses. Alexandru would keep the corn quotas that he refused to hand over in 1951 here, a year leading up to his arrest.

Photo 9: The remaining ruins of Alexandru’s house. He would tell his youngest, Ion, that he was not afraid of his life, despite how they “beat him up and humiliated him, among many injustices and atrocities.” Even after his release in 1953, he would still be followed by the federal agency.

Photo 9: The remaining ruins of Alexandru’s house. He would tell his youngest, Ion, that he was not afraid of his life, despite how they “beat him up and humiliated him, among many injustices and atrocities.” Even after his release in 1953, he would still be followed by the federal agency.

Photo 10: The fountain where, on the morning of January 7, 1961, after his release, a federal source spied on Alexandru complaining to the village shepherd, Iernuțan Pavel, saying, “How long will they stay and make fun of us? Because they took everything from us and only, they don't give us a single pair of cattle to take to the mill.” The quotas they were demanding were high, even clothes, gates, grain wheat, and anything he had in the yard.

Photo 10: The fountain where, on the morning of January 7, 1961, after his release, a federal source spied on Alexandru complaining to the village shepherd, Iernuțan Pavel, saying, “How long will they stay and make fun of us? Because they took everything from us and only, they don't give us a single pair of cattle to take to the mill.” The quotas they were demanding were high, even clothes, gates, grain wheat, and anything he had in the yard.

Photo 11: A picture of Ana (left) and Andra, the sister of the photographer.

Photo 11: A picture of Ana (left) and Andra, the sister of the photographer.

Photo 12: A portrait of Ion (b. 1940, 82 years old), the youngest son of Alexandru. He was expelled from the school during the communist regime because he was born in a family of “cheabur.” He attended National Highschool "Alexandru Papiu Ilarian," Târgu Mureș, but had to give up his education after his father was imprisoned. He says, “I had to lose sometime, a year until my father came back. By the time he got out of there I had to lose something.”

Photo 12: A portrait of Ion (b. 1940, 82 years old), the youngest son of Alexandru. He was expelled from the school during the communist regime because he was born in a family of “cheabur.” He attended National Highschool "Alexandru Papiu Ilarian," Târgu Mureș, but had to give up his education after his father was imprisoned. He says, “I had to lose sometime, a year until my father came back. By the time he got out of there I had to lose something.”

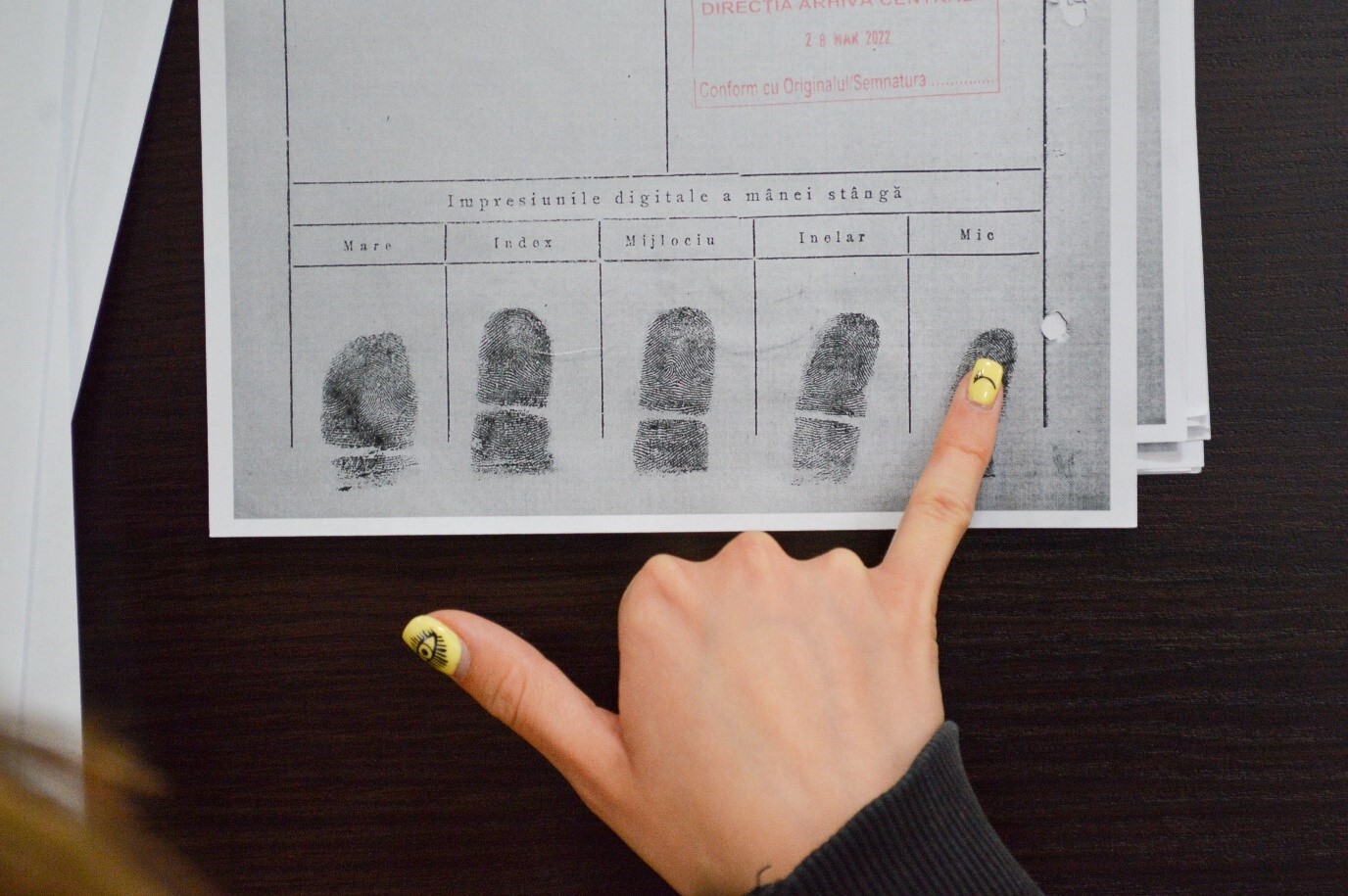

Photo 13: Fingerprints of the Past: The prints of Alexandru, the great-grandfather (b. 1904), and Andra, his great-granddaughter (b. 2004).

Photo 13: Fingerprints of the Past: The prints of Alexandru, the great-grandfather (b. 1904), and Andra, his great-granddaughter (b. 2004).

Photo 14: Driving past: Andra leans on the car’s window as they drive past the village after concluding their “nostalgia trip.”

Photo 14: Driving past: Andra leans on the car’s window as they drive past the village after concluding their “nostalgia trip.”

“Besides the university project, it has more to do with my spirituality because it reconnects me with the past – of my family and my country. I was especially close with Ion, and I’m happy that I could document this story before they’re gone,” Denisa closes our interview, as we come to a conclusion: “It’s important that we grow from our flaws because the first step of improving is recognizing the mistake. The 1989 fall of communism in Romania wasn’t a long time ago, and it’s going to take a while to eradicate that mentality, but this is one step forward to a better future.”

(Photos: Denisa Moldovan)